I have always liked writing. I was encouraged to write by Alister Brass. He was very much my mentor. He died of AIDs in 1986. He was a great guy. I have kept writing. He had taught me a lot about myself, and how someone who was a little older than myself could have lived a fuller life than mine. I miss him every day.

I always wonder where Murdoch fits in all this. Alister’s father, Douglas, was one of Murdoch’s first editors. I think he had a big effect on Murdoch, in the days when his world may have been that of the idealist.

However, I worry about all this technology that has sprung up in an unregulated space and where the forces of good and evil are constantly doing battle. Can I, for whom my first written words required an inkwell – when even the biro did not exist – adapt.

I find myself living in a world in a space which is getting smaller because the demands for instant everything have become the norm – money and fame are generally high on the instant agenda. Words are airbrushed away.

So, why bother to write? Because I want to, and I have little time left. So here goes.

I wrote my first blog at the end of March 2019.

Now this is the sesquicentenary of that first blog, which has been written every week for 150 weeks. That means that in six blogs’ time I will have reached three years of essentially vanity press. Perhaps I have ten people who regularly read it, but unless you hover over your statistics, who really knows. But it soon occurred to me that I like writing – in fact these are my memoirs, one way or another. My attitudes are on show. As I started serious writing under the tutelage of Alister Brass, that relationship enabled me to enjoy the company of a polymath before his life tragically was cut short.

The first blog praised Jacinda Ardern, and I received the rounds of the contumely by a mate, who saw her as a fraud. Thinking about what has happened since that time, I was closer to the mark.

In the last blog I, who once was a tall poppy but tried to dance with the “wolverines”, gave some advice based on this experience. I once knew a person who, like Grace Tame, had a strong profile (at one stage being pictured on every evening edition of the Melbourne Herald depicting the successful beautiful young professional) and saw later at firsthand what she endured.

In the last blog I, who once was a tall poppy but tried to dance with the “wolverines”, gave some advice based on this experience. I once knew a person who, like Grace Tame, had a strong profile (at one stage being pictured on every evening edition of the Melbourne Herald depicting the successful beautiful young professional) and saw later at firsthand what she endured.

As for my advice to Grace Tame, another friend expressed with disdain from his Araratic heights why would I bother. Well, I did and hope she ends up more Eleanor de Aquitaine than Jean d’Arc, with that antagonistic segment of our population either repentant or neutered.

Opinion or opinionated. Well, a blog is a legacy. I notice over time I have altered the blog; by and large I have dispensed with guest writers, become more prolix and recognised how technology has enabled me to dip into the international media. The downside is that those magazines, the delivery of which depended on the US Postal Service, have virtually dried up in COVID times. The Guardian Weekly and The Economist subscriptions fortunately have not been interrupted, although I also receive them online.

Exhaustion

The problem with the persistence of coronavirus in one form or another is that the Australian population is exhausted and, despite their bluster, governments have given up, except Western Australia which remains defiant.

Lockdown indicated that the governments of the Federation were prepared to fight the virus, the fear of which prompted a strong vaccination response in the adult community. In the first wave before vaccination was available, there was an appreciation across the community of the need to lock down, with a ban on almost every movement. At that time, there was a high rate of acceptance of this strategy by the community. Thus, when the Virus spread to nursing homes, the media swooped on the relatives waiting outside with their plaintive complaints.

How life has changed, with daily deaths mostly no longer getting even the perfunctory acknowledgement which they once got at the daily news conference. Borders were a weapon in illustrating how much one State was performing better than another. The only consistency through all this has been the complete ineptitude of the Commonwealth Government, which refused to accept that Constitutional responsibility for quarantine was its – and its alone. That is one reason there should not be any electoral forgiveness.

It allowed that stupid sophistry about personal responsibility to be let out of the Pirouette’s ideological kitbag. Underlying such a statement is a belief that information in the health sector is symmetric – time and time again this has been shown not to be so.

The various responses, whether to children’s vaccination, boosters, wearing of masks, social distancing and the use of hand sanitisers, show differences depending on demographics.

What is the present state of play? Personal responsibility has degenerated into a fervent wish that Australia must have passed the peak – however that is defined – of the pandemic. Booster and child vaccination are lagging because there is no spur.

Pity that another variant has appeared.

The Canoe Tree

There are many canoe trees scattered throughout Victoria, South Australia and NSW and one wonders, given the revival of many old traditions, why more bark canoes are not being made and the craft celebrated. After all, the popular smoking ceremonies were adopted from the American Indians who were here during the Year of the Indigenous.

One area in Southern Australia where there do not seem to be canoe trees is Tasmania, although there has been publicity surrounding bark canoes recently being made with intention that they be part of the biennial wooden boat festival. It is one thing to mimic the past, but the construction should demonstrate the authenticity of being able to float an agreed distance, bearing a person using a spear as a paddle, especially down the D’Entrecasteux Channel.

In 2011 Major “Moogy” Sumner, a Ngarrindjeri and Kauma man, crafted a bark canoe on Ngarrindjeri land, the first recorded in over 100 years. These people live at Raukkan on Lake Alexandrina and move between there and Port Pierce on the Yorke Peninsula. Major Sumner has been photographed standing on the canoe with the spear/ paddle, and therefore the assumption was that the canoe was waterproof and navigable, at least on the lake. His people are river people and before “trouser time” they existed on a diet of littoral birds, eggs and vegetation such as samphire.

Sumner later said that creating his canoe reconnected his communities with the traditional art of canoe-building. There does not seem to be much evidence of modern bark canoe manufacture beyond this effort. In such a riverine culture a bark canoe was an essential item, and as such it is surprising that revival of the art has not received more attention.

It may be argued that stripping trees of bark would have severe consequences, particularly on the river red gum and stringybark population. The Aboriginal people live in harmony with their environment, as we all know and thus this would not be a problem.

In his book about Australian Aborigines, Thomas Worsnop describes the construction of the bark canoe in Southern Australia:

In constructing a bark canoe a suitable tree, generally a large red gum, is selected, and always one that was bent, or that had an outward bulge on one side. On that side the bark is marked out or cut by painted dots, or by notches in the shape of an elongated ellipse, approximating as nearly as possible to the shape of the canoe itself, after which by pressing the wooden handle of a tomahawk and a pole between the bark and the wood the sheet is carefully removed. The outside roughnesses of the bark then are pared off, leaving the thin, hard, and woody inside shell, and the sheet is placed over a fire of red hot ashes to cause the ends and sides to be gathered up and brought together.

These canoes are of very light draught. With one or even two blackfellows, the draught is seldom above 3in or 4 in. Some that I have seen on the River Murray will carry a considerable load; but, being quite round on the bottom and without any keel, they overturn with the greatest ease imaginable.

Later he describes the Montagu Island canoe:

Bark canoes were used by the coast natives of New South Wales; they were from 6ft. to 10ft. long, and 2ft wide. A sheet of bark of the desired length and breadth was stripped from a straight stem and the two ends scraped until they tapered to a very thin edge. These thin ends were then raised by being creased into ridges, and gradually pressed close together. A peg was then driven through the folds at each end, and the bark twisted round to keep the sheet from slipping back. The sides were kept apart by sticks sharpened at each end and placed across the canoe, and it was ready for use. It was propelled by sticks used like paddles, or by small sheets of bark held in the hand; the largest of these canoes would carry five or six natives safely across the strait, about two miles wide, which separated Montagu Island from the mainland.

Ironically, the best recent depiction of a bark canoe construction was shown in the 2006 film, appropriately named “Ten Canoes”. “Ten Canoes” was inspired by a photograph shown to film director Rolf de Heer by David Gulpilil. The picture was of group of ten native men in their bark canoes on the Arafura swamp in East Arnhem Land. The photo was taken by anthropologist Dr Donald Thomson, who worked in central and north-eastern Arnhem Land 70 years earlier, during the mid-1930s.

Among the old men of the tribe, the film makers found some who remembered the craft and were able to make the canoes. There is no mention of whether the canoes were made with stone tools or with more modern equipment. Nevertheless, in the film they seem to be very functional. Again, this film seems an isolated tribute to the bark canoe.

Yet the canoes made in the Northern Australia were generally dugouts, either in the manner of their Melanesian neighbours or were seen to have prows fashioned after the Macassar canoes. So, the bark canoes that were featured in the film negotiating the Arafura Swamp would seem unusual.

It seems difficult to work out why the Aboriginal people are loath to make bark canoes in the manner of their ancestors Thus there is one challenge in Tasmania – build a bark canoe that can reach Montagu Island as your forefathers did. Go to it. If a whitefella like Thomas Worsnop in 1897 has set down clear signposts, so should the tradition be still handed down among the Aboriginal people, rather than exist in a few isolated pockets.

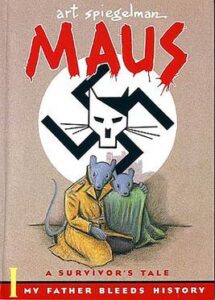

Maus

A guy called Art Spiegelman has written a children’s book about the Holocaust called “Maus”. My Swedish friend has pointed this piece of censorship out to me.

To ensure the book will be a best seller, the McMinns County Board in Eastern Tennessee, known as the Midge State after its Senator, has banned the book.

The Board said by way of explanation (sic):

“One of the most important roles of an elected board of education is to reflect the values of the community it serves. The McMinn County Board of Education voted to remove the graphic novel Maus from McMinn County Schools because of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide. Taken as a whole, the Board felt this work was simply too adult-oriented for use in our schools.

We do not diminish the value of Maus as an impactful and meaningful piece of literature, nor do we dispute the importance of teaching our children the historical and moral lessons and realities of the Holocaust. To the contrary, we have asked our administrators to find other works that accomplish the same educational goals in a more age-appropriate fashion. The atrocities of the Holocaust were shameful beyond description, and we all have an obligation to ensure that younger generations learn of its horrors to ensure that such an event is never repeated.

We simply do not believe that this work is an appropriate text for our students to study.”

I have published the whole piece, including the last paragraph written by the resident weasel. “Maus” is about the Holocaust – it depicts violence and suicide. Well, your forefathers were very fortunate in settling in the shadow of the beautiful Smoky Mountains. And as for profanity – eight words; and nudity – a naked mouse!

To be fair I have not read the book, but I have ordered it to see what the fuss is all about. I am not a fan of censorship, except in the case of demonstrated sedition.

By the way, the county seat is Athens, somewhat ironically named.

The Nickname

Michael Rowland from ABC Breakfast has done us all a service by refusing to refer to either the Prime Minister or the Leader of the Opposition by their nicknames. This is not to say that these names will not still have general usage in the bar at the Kembla Grange races. Even Menzies had a nickname – “Ming” – but it was not in common usage when discussing his everyday activities in the public media. His enemies dubbed him “Pig Iron Bob” because of his unfortunate advocacy of iron being exported to Japan before the Pacific War. But in the political commentary it was Menzies and successively Chifley, Evatt and Calwell – maybe first names were used – but not Mingo; Chifo, Evo or Caldie.

It’s all a matter of perspective. I find it confronting when a youngster calls me by my first name because for me the divide in how I’m addressed should reside within myself. A Christian name implies a degree of licence, not to be used by all and sundry.

However, if the Honourable Antony Norman Albanese or the Honourable Scott John Morrison want to dispense with any of their given names or titles and be known as Scomo and Albo, no wonder some may think that they write their policies on the back of a beer coaster or a tithe receipt.

As a postscript, I read the comments of a journalist attempting to devise a smart comment about “Albo”. Obviously, as a child, the journalist had done a couple of lessons in Latin and equated “alb” with white, since the Latin (and incidentally also the Romanian word) for white is “albus”. However, in Italian “bianco” is white, “alba” is dawn and Albanese “Albanian”; in Latin “aurora” and “Ilyrii” respectively.

There is a strong link between Albania and Italy which goes back to Roman times, but I seem to have drifted a long way from Michael Rowland’s timely comments. Still, the association between Albania and Italy is worthy of another blog.

The Virtuous Cycle

Over the next four years, the Morrison Government will invest more than $13 billion through the Education portfolio alone to support research in Australia, including $8 billion in research block grant funding.

“This includes the Trailblazer Universities program recently announced by the Prime Minister. Trailblazer gives four universities access to more than $240 million to build world-class research commercialisation capability.”

So runs the media release from Minister Robert this week. It came at a time when the Boston Globe has produced a comprehensive article on the biotechnology research around Boston, which I have reproduced in an abridged version without distorting the content of the original article. It should be remembered that, in the context of the article, New England has a population of 15 million, so it provides a significant comparison with this country, where all the biotechnology expertise has also been concentrated in a select number of institutions.

I participated in the Wills Medical Research Strategic Review, which Michael Wooldridge commissioned in 1998 and which resulted in a report with the optimistic title of the Virtuous Cycle. One of the areas of recommendation was the commercialisation of research – and with a somewhat wry smile, I note the new jargon, the Trailblazer Program. Back in early 2002 it was the Flagship program launched by the CSIRO, as if in response to the Will’s Report. I’m not sure “what oceans the Flagships are now plying”, but perhaps the trailblazers will find out.

Now back to New England and what the Boston Globe has to say about the matter. No flagship has been reported off Cape Cod, but perhaps nobody was looking, except that “Flagship” is part of the title of Moderna’s venture capital offshoot.

It’s almost like Massachusetts has too many biotechs.

The industry is hotter than ever, with companies routinely raising millions of dollars in venture capital, startups blooming on a weekly basis, and developers planning more lab space seemingly by the day. But the pipeline of qualified workers to fill all of the added jobs can’t keep up with the burgeoning demand.

The market for biotech talent in Massachusetts has long been robust, but lately the crunch has turned critical. That’s causing some in the industry to worry that it will not only inhibit growth, but also affect the quality of work as key positions become harder to fill and lower-level workers jump from company to company in search of a better compensation package.

Hiring “is definitely more competitive than it was a few years ago, there’s just no question about it,” said Michael Gilman, chief executive of Waltham-based Arrakis Therapeutics, which more than doubled its staff during the pandemic.

The surplus of startups reflects investors’ desire to pour more money into the world’s leading biotech hub. But with every new company that comes out of stealth mode or a mega-funding round that comes with mega-hiring goals, the people problem has gotten worse.

According to the latest report from industry association MassBio, nearly 85,000 people work in the state’s life sciences sector, up 55 percent from 2008.

Most of the hiring is happening in Cambridge, where companies posted more than 2,630 biotech job listings

Large companies, such as Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceutical, as well as Moderna Therapeutics and its venture capital backer Flagship Pioneering, were seeking the most workers during that period.

Turnover is on the rise, too. About 16.5 percent of life sciences employees in Massachusetts voluntarily quit their jobs last year, a recent survey from research firm Radford found, up from 13 percent in 2018. Both figures are high enough to affect a company’s effort to grow.

Naturally, one way to recruit and retain people is to keep paying them more.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average salary in Massachusetts for chemists and scientists was about $100,000 in May 2020. But biotechs are finding that historical data and closely watched benchmark surveys from Radford quickly become outdated.

“One of my companies realized they had fallen behind in some positions by more than 10 percent,” said Tony Mullin, a biotech human resources executive. “They offered $130,000 and were losing candidates because they were getting $145,000 or $150,000 from other companies.”

Executives said some firms seem to be aggressively outbidding each other for candidates, though most agreed it isn’t a sound strategy.

There’s also a sense that employees are easily swayed by “title inflation,” a phenomenon that occurs when people climb the corporate ladder faster by bouncing around.

There’s a short-term satisfaction with getting a bigger title, but then along with it comes expectations of success.

Beyond compensation, biotech firms are also paying close attention to perks and benefits. It’s not uncommon for companies to have ping-pong tables in their offices or to provide catered lunches Silicon Valley-style.

Dyno Therapeutics’ new office will have a rock climbing wall. Relay recently began offering employees free diapers for the first year of a child’s life. Pet insurance is becoming more common.

One option in expanding the talent pool beyond Massachusetts is an “easy way to kind of simplify the problem for yourself” in a tight labor market. But hiring too many remote employees to fill job openings could be a quick fix that forever changes what it means to work in the biotech epicenter of the world.

When it comes to culture and career development, it has been found that being local is really important, both for the company and the employee.”

Adam Koppel, managing director of Bain Capital Life Sciences, said he often gets asked about what could slow the momentum of the Cambridge-Boston biotech ecosystem.

“The proliferation of new companies has created somewhat of a supply and demand mismatch in the marketplace for skilled managers,” he said.

Koppel said the talent pool has not matured enough to fill key areas from the C-suite and clinical development, all the way through to the commercial launch of products. And, he said, there is increasingly competitive intensity in the industry due to many “copycats” that are “going after the same targets.”

“The ecosystem could benefit from a certain degree of consolidation,” he added.

At least for now, though, executives seem to believe that the biotechnology business in Massachusetts will keep expanding, regardless of its hiring and retention problems.

“It is conceivable that all the capital dries up in our industry, companies shut down, lay off scientists, and they have no place to go,” Gilman said. “I don’t see that happening anytime soon, honest.”

Mouse Whisper

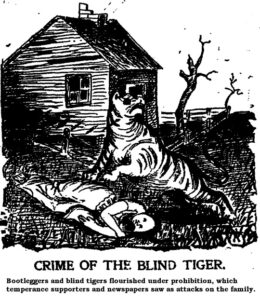

Welcome to the Year of the Tiger. Watching the Cincinnati Bengals reaching the Superbowl reminded me of a discussion I overheard while I was tucking into a piece of manchego that one of them had dropped on the floor.

It concerned a blind tiger, and apparently my Mäuseherrin has a T-shirt with a blind tiger featured on it. She acquired it in a downtown Cincinnati tavern from the owner, who had an Australian boyfriend and given they had wandered into her joint about midday when business was slow, she had time for a chat and told the Australians about the name of the tavern. “Blind tiger” is one of the nicknames for a speakeasy, during Prohibition. The joke was that you paid to get in to see the blind tiger – and the drinks were free.

I wonder how long that ruse lasted before the police moved in.