After not being given sufficient time to explain my remarks re Brett Sutton last night on Q&A what I wanted to explain is that he is not an Epidemiologist and it is on his medical advice to Govt that we continue to have shut downs. If I have offended Prof Sutton my apologies.

Q&A is a pulpit. A woman called Susan Alberti AM, AO, AC, a stepping stone queen of Order, developer extraordinaire, professional philanthropist and general Liberal party lady about town cast a nasty aspersion against the Chief Medical Officer of Victoria, Brett Sutton, on that ABC program this past week. She said he was not a doctor – a sotte voce interruption when Tom Elliot was in full flight. Now I have never watched Tom Elliot, because he is a Melbourne phenomenon, or perhaps I have had enough exposure to his father to last a lifetime.

However, I was directed toward this excerpt of the program, which I rarely watch. It brought back memories. Here Mr Speers was conducting this meeting of the Coalition with a guest from the Opposition. He seemed to be acting as President of this newly-formed Q&A Branch of the Liberal Party, where Tom Elliot had been invited as the main speaker. I had heard of this chap as he was at university at the same time as my offspring.

I had known his father from his days at the University of Melbourne, where he was several years behind me but had a refreshing Baptist School old boy attitude to beer, billiards and of course fags, however defined.

It was refreshing to hear all the nostrums with which his father used to amuse us. Listening to Young Tom I had never realised his father, Old John, was such a fine ventriloquist. Moreover, Old John did not appear to be in the room – what a feat.

What I objected to however was the lack of immediate correction about Brett Sutton. Speers should have stopped the meeting and corrected Alberti immediately. Even in her apology, she says he is not an epidemiologist. Well, Alberti, not all epidemiologists are doctors—and to be Chief Health Officer, he does have to have a medical degree and has had extensive overseas medical experience, just not restricted to counting the dollars in the fields of Dandenong and Hallam.

Her sidekick, The Moroccan Soup Bar kid, Hana Assafiri OAM, had chimed in at the same time with the same comments, but also scrawled some sort of an apology: “unequivocal apology on getting your title wrong! The intention was to convey that you are not simply a doctor, that you heave (sic) a wealth of expertise guiding this state through the pandemic. Obviously didn’t translate the way it was intended.” I do hope, Hana Assafiri, that your pigeon pastilla does use icing sugar not iodine – sweet not bitter taste on the pie.

Stop the frolic! David Speers as a balanced chair of an ABC program, I’m afraid you are a disgrace. Full stop.

And as for Susan Alberti, my total contempt, made worse by your awkward misstatement, which is in no way an apology.

Brett Sutton is the hard man; he is one who is identified with the lock up strategy, whether fairly or unfairly. The above comments are not the only ones floating around about him. In crisis situations, you need hard men and women who can differentiate self-interest from legitimate criticism; who have a clear view of the end point. Often a lonely job.

Toilers from Homes?

A cognitive scientist by training and a working mother, has been warning about the unintended consequences of workplace flexibility, including the mental toll on mothers who still do the brunt of the housework.

The scientist stresses that managers can’t just leave it up to workers to figure out the right balance. Companies, for example, could decide there are certain times when everyone is in the office as a way to head off problems arising on work-from-home days when employees are out-of-sight, out-of-mind.

Employers could also decide not to schedule meetings at certain times of the day — such as before 9 a.m., between 3 and 4 p.m., or after 5 p.m., allowing parents (note change from above) to make school drop-offs and pick-ups, and to prepare dinner.

This expresses concisely the sentiment for developing a hybrid model of working both at home and in the office that has become the preferred option for services where front of house or on-site physical activity are not required. This describes much of the so-called gig economy.

The quote above concentrates on women to the exclusion of men.

The hybrid model is constructed with women in mind, given they inevitably are primarily responsible for children and the domestic arrangements, which all need to be sustained when she is at work. It also recognises the increasing number of women at all levels of bureaucracy – they are not just the stenographers of yore. Nevertheless, for many women the nature of their work does not give them the option of a hybrid model of remote work.

So the tug-o-war now applies to the bureaucracy however defined and be it public or private sector, responsible for delivery of product without need to be on site. The recent addition of teachers to that group as “remote learning” becomes easier to set up is an added complexity.

However, does the person in the street benefit when seeking advice or resolution of their particular concern if the hybrid model becomes generalised?

The problem is in the implementation of what could be construed as “new” bureaucracy. For the person who, by the nature of his or her job, requires a large amount of time to think, create or write, the wish to work without distraction is understandable. After all, Silicon Valley is always quoted as that – of having the libertarian approach to workstyle.

But even here, to quote a CNN source: The tech industry might seem well-positioned for remote work indefinitely but it has also spent years building a culture of collaboration and innovation that it will be loath to give up, spending untold billions on huge offices and perks like free food, gyms and nap pods that convince employees to spend more time there than they do at home.

But this above is not conventional bureaucracy nor is it one which is female dominant. Or is it just the vanguard of a “new” bureaucracy created by the pandemic where a larger proportion are women?

It may be reasonable to postulate that most people working at home have a need for ongoing communication – in no way different from working in the office. Thus, “rules of engagement” need to be clarified. The last paragraph of the cognitive scientist’s assessment needs better definition. There must be discipline imposed on the environment where children need to be picked up and domestic duties resumed. Does domesticity take priority over the requirements of the job; one unpredictability being illness in the children – as one of my colleagues once said, “young children are bags of virus”. It is here that the father is introduced into the hybrid model discussion.

This is the contingency which needs to be addressed if working at home is accepted as part of the hybrid model. These gaps need to be patched in the structuring of rules. In the office situation, employees take carer’s leave, or sick leave to deal with these situations, or negotiate short working days.

As soon as rules are established there will be exceptions. If the rules become the subject of an industrial award, work flexibility becomes beset with the legal rigidity of industrial contracts – with the temptation of putting in place “one size fits all”.

The problem with work flexibility is that communication becomes increasingly difficult. Over the years, unless you happen to be the person of influence, to get in touch with “the responsible bureaucrat” in the office can be bad enough, but away from the office can be a nightmare when you want urgent resolution. There are so many reasons for having a day off and thus the decision-making is even further delayed or even forgotten.

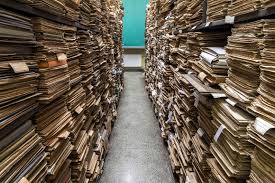

When this is added to the actions of paranoid Government departmental heads who seem to keep their staff on the move until the corporate memory becomes totally attenuated and thus is finally lost. Then “the wheel has to be re-invented” and the same mistakes are liable to be repeated.

How many times have I had to face bureaucrats with no sense of what has gone before; who are unaware of what works and what doesn’t work? That is the problem with much of bureaucracy when it loses its corporate memory – there is a tendency to start the same process all over again, especially when there is a change in government.

Now introduce into that mix working from home without rules.

How often do you try to contact a person only to be told he or she is working from home? This is said in the sense the person is incommunicado until he or she returns to the office. The person may as well thus not be at work. So, if working at home becomes accepted as the new norm, then the bureaucrat needs to be contactable at home and must be prepared to sacrifice the privacy of the home as an “inviolate castle of domesticity”.

Where flexibility of the hybrid model is maintained alongside strong productivity, I suggest it is due to the leadership – what Max Weber called “charismatic”; but such leadership is difficult to sustain, because so much of the work pattern is determined by the leader, and the quality of that leadership. The charismatic leader leads, and then does the hybrid work model revert to a bureaucracy? I am not sure that the hybrid model has longevity; because long term “charismatic” leadership is the exception in the life of any bureaucracy – longevity is not its strong suit.

A somewhat sarcastic Bartleby opus in The Economist suggested that working from home on a Monday or Friday is a joke. On the latter day, as Bartleby writes, managers may call to listen out for tell-tale signs of the beach or golf – a comment, both sexist and ageist. Bartleby’s point is made about ageing men.

Yet if the hybrid model becomes an object for gaming and maximising “slacking”, then the above article has a set of tips. If hypothetically two days at home working are allowed, then there are ten combinations – and Monday and Friday may just raise suspicions, if not hilarity. Again, gaming is not restricted to one sex.

In the end, like the cognitive scientist’s thinking, I suspect the office environment will win out against the hybrid model, because as the final paragraph of the opening quote implies, the home environment will breed conflict within the job framework – unless the office can be made totally separate and distinct from “the hearth”.

Yet there is at least one more elephant in the room, and that is the increasing resistance to people coming into the office with an upper respiratory infection. I suspect that a population which has come through lockdowns, mandatory masks and forced compliance will be less tolerant of anybody who challenges the health of the office by coming into work, even with a common cold.

More thought needs to be given to childcare services provided under the aegis of the State to mirror the new workstyle of those who need to use them. It is worth more than an addendum to an apologia or not of the work hybrid model.

Schools work on fee-for-term model, so that the fees make allowance for absences. When I was chairing a childcare co-operative, until that “term” business model was adopted, then the income of the childcare facility suffers from the vagaries of domestic problems – child illness being a big slice of that.

With the increasing discussion, albeit demand for a hybrid model, then childcare services usage may have to change to reflect that change in work practice. That is another topic to be explored in a future blog, when reminiscing over personal experience, admittedly many years ago, which nevertheless may still provide productive comment.

I knew it well, Dunmunkle

As I promised, I write my take on the three towns which once were the three Townships of the Shire of Dunmunkle in the Victorian Wimmera, north of Horsham.

I used to know this area reasonably well since I was asked to resolve an issue around the delivery of health care in the 1980s at one of these townships, Minyip and went back over the next decade or so. The other two townships are Murtoa and Rupanyup. Minyip traditionally is a Lutheran town, part of the Protestant German diaspora which is layered across Southern Australia from the Barossa Valley to the NSW Riverina around Albury. By contrast, Rupanyup has Scottish Presbyterian heritage and Murtoa, Irish Roman Catholic.

Rupanyup lies on the Dunmunkle Creek, which flows into the Wimmera River. Murtoa lies on the major Melbourne-Adelaide railway line. Minyip is surrounded by wheat cropping, and once was on a spur railway line.

Watching the “Backroads” program on the ABC, I was fascinated by one item, and wondered why I have missed it. The second was the fact that Murtoa was ignored while, the program concentrated on Rupanyup and Minyip. That puzzled me, especially as the most interesting item in the program was the huge Murtoa grain store built in four months during World War 2 at the end of 1941, which is the only one left in Australia – the so-called Stick Shed, because it has 560 mountain ash poles supporting a galvanised iron roof structure, the building spread over four acres, and held up to 92,000 tons of wheat. The sloping roof was built in the way wheat grain naturally stockpiles itself. A majestic bush building but working inside must have been a major industrial hazard.

The other puzzle was why Murtoa was otherwise ignored. After all, it was the birthplace of Mary Delahunty, one of the most well-known ABC faces and the ABC tends to identify and remember its own. Therefore, the puzzle is why the program ignored Murtoa until almost the last frames, given that it is also the biggest of the three towns.

The tactic of the “identity” is the method of packaging the half-hour program, which inevitably gives a caricature of rural life; so different from the rural program “Landline”, which is genuinely informative about rural life. In fact the segment on Rupanyup, which is the one township struggling to survive, concentrated on chick pea production and its diverse uses, and could have as easily segmented into “Landline”. This diversification into pulse legumes around Rupanyup starting in the 1980s with field peas extended to many of the other crops, in particular lentils and chick peas, the latter most visible in the supermarket in the form of hummus. But what does that have to do with Rupanyup, the few views of the township are a tableau of peeling paint and empty shops?

I got to know Minyip when they closed the local hospital in the late 1980s and replaced it with a community health centre, which for many years had the advantage of continuity in its administration. The closure of a hospital, even a small one as happened in Minyip, made me realise that when you close a small hospital, as I have written “it is like a death in the family”. The community traditionally was born and died in the hospital. When services are rationalised even when a community health centre was constructed and proved to be excellent, the community’s grief can be underestimated.

I suspect it is less so now, presumably with dilution of the Lutheran influence. After all, in 1935 the congregation decided to move the Lutheran church with dimensions of 16 x 8.5 metres including the 19m high bell tower, 50 tons in all, a distance of 10 miles to Minyip. The congregation jacked it up onto a 12-wheel jinker and by means of a steam traction engine moved it to its present site in the township. The trip took three days. Would it happen today?

The other anecdote worthy of note was in the early days of settlement when they decided to put the shire hall in Minyip, the Murtoans came across at night and took it to Murtoa. Minyip retaliated by taking it back, in a clash of the jinkers. Then it burnt down; and for years there was a residual animosity between the two communities.

Generally, the animosity or rivalry, however defined, is worked out on the football field. In 1995, with a declining pool of players, old grudges were forgotten; the Murtoa and Minyip teams amalgamated and the jumper was redesigned to absorb the colours of the two football teams. Rupanyup has been the outlier, in that its football team dropped out of the Wimmera League and down to the Horsham and District league.

The other characteristic of townships such as Minyip is that they provide cheap lodging, and therefore the problem of the traditional farming town becoming a refuge for welfare recipients and again as the community ages, the elderly members are loath to leave and they retire into towns. These towns become wellsprings of rural poverty.

At least that was my observation when I was a frequent visitor. At the time I wondered whether this continued to feed the sustainability of these tiny townships. There were pockets of rural poverty scattered across rural Victoria. The extent of the poverty could be titrated by their closeness to provincial centres. Whether that holds now in these centres, I know that for other small towns with which I have been closely involved in the intervening years, the answer is probably yes, but immigration and other social movements have changed the 1980s profile of some of these small townships, including gentrification.

Now what was Minyip to “Backroads”. The impression given was that its continued existence due to it being the set for the Flying Doctors series, and then as a convenient backdrop for other films, The Dry and the Dressmaker. Eric Bana on the first floor veranda of the local pub was not Minyip, any more than the war memorial to commemorate the Relief of Mafeking in the main street is. They are props – but they are not Minyip.

Backroads is undoubtedly entertainment, and rural Australia does have its identities, its eccentricities but it is pity that the series provides no thread, no clues to the reasons for their survival – and Australia has about 14,000 settlements with less than 1,000 people.

The diversification of cropping – is that the reason for Rupanyup? The occasional movie set – for Minyip?

Or else is there a more general reason for the persistence of settlements that you would have suspected to have outlived their reason to being, and yet not obviously changed their role?

El Obrero

I have become immersed in the Portuguese language, which is a somewhat schizophrenic pursuit. Most of the teachers – in Sydney at least – are Brazilian; my initial teacher has been a Portuguese national. There is a strong representation of both cultures through the respective communities in Sydney.

Therefore, I was intrigued for us to get together for lunch at the Portuguese Community Club, which is sequestered in the industrial area of Marrickville, an inner suburb of Sydney. The club is signified by a fading sign directing our car along a potholed pavement. The club has a grass area in front of the entrance resembling an old bowling green, but the building is squeezed between two railway lines, yet access is easy. No problem parking here, unlike most of suburban Sydney can be always very problematical

Inside the club it is very plain, and those at lunch were workers, some in their steel capped boots and hi-vis vests. Voluble in exchange in Portuguese it was just what it purported to be – a working man’s club. Our group of four were the interlopers, two were woman. Our garçom was a Nepali with a good grasp of Portuguese learnt paradoxically in Australia.

The food belied the surroundings. It was superb – my steamed clams – amêijoas also with an Italian label “vongole” in the menu, followed by grilled quail with the signature vinho verde to wash the food down.

The spare surroundings reminded me of another worker’s restaurant we were introduced to in La Boca in Buenos Aires. We had asked the driver if we could go to a place to eat which was typical of the “working La Boca”. He said nothing but just dropped us off in front of the nondescript building. After all, La Boca is a substantial port area, although it is known for tourists wandering the narrow streets with the gaudily painted buildings, street dancers performing the tango and stalls covered in cheap knick-knacks. All Porteno kitsch!

So different from the unprepossessing place with the barred windows, four-panel brown door and the old washed-out Coca Cola Sign juxtaposed against the green restaurant sign above the doorway.

Such a modest entrance, but once inside, the dining area was long and expansive. The walls were covered in photographs, including the obligatory one of Maradona. From the ceiling had been hung football shirts, from teams all over the world, like an international clothes line. We were early for lunch and were ushered to a table on the side where we could see the incoming tide of workers, who quickly filled up all the tables.

The Italian influence is strong in the menu; agnolotti, parmigiana, calamari – but the carafe was the local tinto. Nobody spoke English, but in the hubbub, it was easy to indicate what you wanted. We seemed to be the only tourists there; at least we seemed the only diners to be using sign language rather than just gesticulating.

Argentine dining is associated with the parilla – the Argentinian barbecue where it is all beef and firebox. El Obrero like the Portuguese Community Club are authentic restaurants– being able to settle down into a meal which is a cultural experience can never be topped. Yet then again I wonder whether it is possible, as a tourist, to ever be authentic, the truth of which I tried to verify as I riffled through my memories of countries where I have been. I wonder how many times you have to dine in a place to be authenticated – if that is the word.

Mouse whisper

Our surname, he said, was originally ascribed as Mac Aodhadáin around the 12th century. This family are stated to be no ordinary people. They were bardic scholars and brehons – the interpreters of Irish Law. The extravagant statement that without this family, there should have been lost a precious part of Irish history. It was a name that percolated into eighteen Irish counties.

As the author of this family monograph opined “It has been said that a person’s own surname is the key to a doorway on the past. This is because one of the most interesting ways of gaining some insight into history is to follow the pathway of your own names through the maze of documents still preserved in various sources.”

Maybe, but as I found out, my Swedish mouse relative is known as Kyrkligaråtta not Kyrkomus as written in the last blog. A genuine erråtum, I’m afraid.

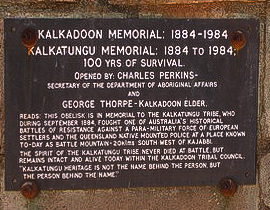

This obelisk is in memorial to the Kalkatunga tribe, who during September 1884 fought one of Australia’s historical battles of resistance against a para-military force of European settlers and the Queensland Native Mounted Police at a place known to-day as Battle Mountain 20 klms south west of Kajabbi.

This obelisk is in memorial to the Kalkatunga tribe, who during September 1884 fought one of Australia’s historical battles of resistance against a para-military force of European settlers and the Queensland Native Mounted Police at a place known to-day as Battle Mountain 20 klms south west of Kajabbi.

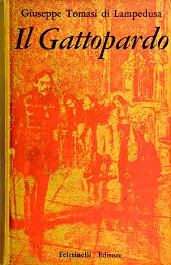

Draghi then goes on with a quote from “The Leopard”, where Prince Trancedi Falconeri says to his uncle Dom Fabrizio, “If you want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Draghi then goes on with a quote from “The Leopard”, where Prince Trancedi Falconeri says to his uncle Dom Fabrizio, “If you want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”