There has been flooding of the Murrumbidgee River this week, and Wagga Wagga has been one city where there has been some flooding. I know the city well, and where the flood seems to have its greatest impact, as reported, seems to be in North Wagga Wagga and particularly the caravan area adjoining the Wagga Beach. It has always been somewhat anomalous to see a sign to the Wagga Beach, which is inland and not on the coast. However, the major rivers – both the Murray and the Murrumbidgee – have areas of sea-mimicking beaches in spots along their respective river courses. One of these is in Wagga Wagga, and after a major flood there is always the chance that one will find pieces of jasper on the beach, as I did once.

My find was a substantial piece about the size of a hand. Jasper is a microcrystalline form of quartz, usually a deep red due to the iron impurities. Further up the River is the village of Wee Jasper, close to the Brindabella ranges south of Canberra and near where the Burrinjuck Dam is located. Wee Jasper was named unsurprisingly by an old Scot who found small pieces of jasper at the site. So, Jasper and Murrumbidgee are linked … as is flooding.

The flooding is not catastrophic, as we crossed the river further north of Wagga Wagga at Gundagai, where the river splits the town of 2,000 people into North and South Gundagai. Here there is a large flood plain. There was evidence of flooding, in fact massive flooding in parts, whereas in other parts there were cattle and sheep grazing on soggy ground. I did not see any houses underwater but then we were on the highway, where the bridgework is high above any flood line. I well remember the old wooden bridge and the old railway bridge – all were constructed high above the Murrumbidgee River and its adjoining flood plain.

Gundagai learnt its lesson early, as in 1852, the whole township was swept away by floods, with a loss of 89 lives, then a third of the population. The death toll, the highest ever in an Australian flood, would have been even more if some of the local Aboriginals had not paddled their canoes out and saved upwards of 40 people. There was a re-allocation of lands so that residences were built above the flood line, but not before the settlement was hit with another flood in the following year.

I have travelled the Hume Highway, the major four lane artery between Melbourne and Sydney, countless times but rarely if ever have I crossed such a flooded Murrumbidgee River. The road builders have got it right.

As the Daily Advertiser reported: Gundagai escaped significant damage over the weekend despite major flooding along the Murrumbidgee River, which peaked at just over 9.02 metres on Saturday afternoon.

Moderate flooding conditions continued on Sunday and State Emergency Service Gundagai unit commander Ross Tout said volunteer crews had responded to one car crash and two livestock rescues.

“We have pretty much finished here as the river is dropping down. We have done a lot of running around with the council to organise the clearing of bridges,” he said. “The river is going to stay reasonably high for a while as they’re going to keep on getting water out of Burrinjuck Dam.

“We were pretty safe here in Gundagai, there were no evacuations, no houses in the water … Gundagai is designed well for floods.”

Run, Oliver Hoare, Run

To my chagrin, I had never heard of Oliver Hoare before this week. This is because if you are a gun track and field athlete, there is no point hanging around Australia. Hoare won the Commonwealth Games 1500 metres against a world class field, in record time. There have been a number of pretenders to the class of 50’s, culminating in that extraordinary win by Herb Elliott in the 1500 metres at the 1960 Rome Olympic games, when nobody came near him. After all, he had heralded this success at the 1958 Cardiff Commonwealth games, when Australia filled all three places in the mile – Merv Lincoln and Albie Thomas finishing behind Elliot.

Elliot inherited the mantle from John Landy, who always seemed to be beaten, because he was the one who ran from the front and therefore he was the sitting target as he was in the Vancouver Games when he looked back over the wrong shoulder and the Englishman Roger Bannister burst through on the outside to beat him; and uncharacteristically in the Olympics Games 1500 metres final in Melbourne in 1956, Landy got caught in the ruck but still finished a valiant third.

I had no idea about Hoare, as I watched him line up for the final of the Birmingham Commonwealth Games 1500 metres. I saw him get passed in the last lap and thought, here was another creditable fourth or fifth coming up. I remembered the career of Craig Mottram, who promised and promised…

Not to be this time. I witnessed one of the great athletic feats by an Australian track athlete, rivalling Ralph Doubell’s win in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games 800 metres, when he overpowered the Kenyan, Wilson Kiprugut, in the last 100 metres, as Hoare did this week to his fellow competitors, including two Kenyans.

Landy, Elliot and Doubell all trained in Australia in an era when athletics was a prelude to a professional career elsewhere, and before the Iron Curtain countries, America and certain of the European countries instigated virtual professionalism and moreover systematic cheating through the various cocktails of drugs, including “blood doping”.

Yet here was Oliver Hoare who, early in the year, had won the Wanamaker Mile at the Armory in New York, where it has been held since 2012. The Prize money for winning is modest: $3,000, then 2nd place $1,500; 3rd place $1,000; 4th place $759; 5th place $500; 6th place $300. Still the event attracts the best middle distance runners in the world.

The indoors Armory track is rubber and the mile requires eight laps of the surface. It makes for a fast race with the speed on from the start by having one of the runners being the designated pacemaker, running the first four circuits before dropping out.

Given that Channel 7 had overlooked him in their pre-game publicity, it was difficult to watch as the following day, the Channel tried to retrieve the fact that their know-all commentator, Bruce McAvaney, had missed this guy. Moreover, they had the cheek to try and push McAvaney to front and centre with Hoare rolled out as an appendage to try and retrieve the Omission by the Oracle. But to be fair, most of us did also.

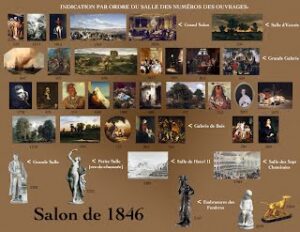

The Salon of 1846

I have just finished picking my way through The Salon of 1846 by Charles Baudelaire, who is remembered as the poet author of Fleurs de Mal. Baudelaire led a dissolute life, but when he wrote his review of the pictures in the exhibition, he was still only 25 years old. As has been written, it was not a particularly good exhibition. There were several major painters of the period who had bypassed the salon.

It was an unstable time in Paris (and France as a whole), as the government of Louis Phillipe was under fire because of the very limited voting franchise – France was shuttling between Empire and Republic, but the great mass of the French people was shut out of government – after all élite is not an English word.

In fact, Baudelaire is writing his review of painting two years before 1848, when Europe was eventually convulsed by revolution provoked initially in France; and against a backdrop of famine across Europe and consequently migration of the oppressed to a “Newer World”, where they might savour freedom.

Michael Fried is the name of a prominent art critic rather than the title of a Salvador Dali picture, and in a foreword to the most recent publication of these Baudelaire’s essays he writes: “Structurally, the Salon of 1846 comprises a dedication (“To the Bourgeois”) followed by eighteen short sections, each bearing a title. Not all the sections are equally crucial to his overall argument, but taken together they are remarkably consistent; the task of someone like myself who seeks to introduce this deceptively simple-seeming text is to do justice to that consistency as well as to the particular vision of painting and criticism it attempts to convey.”

Baudelaire has mastered the skill of every chapter being an island but fitting into a coherent archipelago. Therefore, I find that I can read one chapter, and it makes sense without it being in some continuity. Yet it is not a book of aphorisms – sprinkled with self-conscious wisdom.

It is difficult to excerpt the text itself because much of the criticisms relate to painters who have been long forgotten. Baudelaire admired Delacroix and his interpretation of “la héroïsme de la vie moderne” Baudelaire methodically takes us through not only Delacroix but also another painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, illuminating his belief that “the pursuit of the ideal must be paramount in artistic expression”. With Baudelaire, there is mixture of admiration and disdain, given that the salon audience was predominantly the bourgeoisie, itself in a state of flux as France lurched from monarchy to republic.

I must say that I found the selection of subject matter and paintings hung at that 1846 Salon as all very much painted in shades of umber and russet with splashes of more optimistic colours. They are an incredibly gloomy set that made me feel you are wandering around a poorly lit cathedral. There is a Corot, and I have always liked these almost silhouette countryside paintings. Here exhibited it was Vue prise dans le Forêt de Fontainebleu, which conformed very much to the Corot formula.

But perhaps the pictures of the Red Indians would not be found next to the Biblical Mary or Rebecca. The more you look at the array of neoclassical paintings the more I understood the mood of Baudelaire – the rebel in the style of Stendhal and Balzac; but I am sure Baudelaire had a tricky mind.

Magritte

Among the satirical questions, one asked, is “Name five famous Belgians?”

Well, Rene Magritte was one.

I had always admired Magritte’s paintings. I had a print of Dominion of Light (L’empire des Lumières) in my Melbourne office in 4 Treasury place, then the Old Customs Office. I do not remember which one it was of the 17 versions that Magritte painted, but I loved the juxtaposition of the darkened buildings against the backdrop of blue sky dotted with white cumulus. Surreal; paradox … to me it represented the confusion of life dependent on senses.

To me, surrealism is irony in painting.

I am not on my own in admiration of this work. A 1961 version of Dominion of Light, one of the largest from these paintings of the same name, was offered at Sotheby’s earlier this year. It came from the collection of Anne-Marie Gillion Crowet, the daughter of Magritte’s patron Pierre Crowet. The painting had remained unsold with the Crowet family and was on long-term loan to the Musée Magritte in Brussels from 2009 to 2020.

The price paid was almost £59.4m.

In 1998, a major exhibition to celebrate Magritte’s birth in 1898 was held in Brussels at the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts. It was scheduled to run between 6 March and 28 June, and we belatedly decided in June to go. The problem was we grossly underestimated the availability of tickets and didn’t book ahead. Thus, this intrepid pair set off to Brussels with the belief that tickets would easier to procure on site; only to be proved wrong, so wrong.

We thought Martin Walker, then the European correspondent of The Guardian, whom I had invited to Australia to give the Cowper Oration might be able to help. Despite the fact that he and his wife, Julia Watson, a noted food writer, over dinner at their home in Brussels agreed to help, they also both drew blanks when they tried to get tickets.

As a last resort we went to the Exhibition, hoping that there may have been tickets returned. Again, shaking of heads. Then the clouds opened. A woman who had been listening to our pleas…. that we had come all the way from Australia… that we so loved Magritte… and so on, motioned to us. She was apparently a supervisor and it turned out she had the discretionary power to admit people, if they fitted within certain categories. Thus, we became representatives of an Australian Art Gallery of our name. She whispered you better agree on the name if you are challenged.

Then the deal was done. Courteously escorted through the barriers without ticket, without payment. We had made it. Magritte in all his magnificence lay before us. The exhibition did not disappoint. We were not challenged.

Ceci n’est pas une pipe! It certainly was – in fact “deux pipes”.

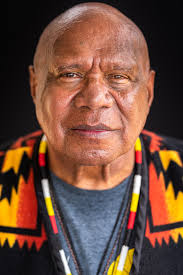

Archie Roach – The Balladeer

Recognition of Archie in the American media, The Washington Post is reprinted below.

On 31 July, the day after Archie died, another magnificent singer, Judith Durham also died. The Washington Post too has acknowledged her contribution in her obituary.

Whose contribution to Australia culture was the more important.

Daniel Andrews, the Premier of Victoria, offered a State Funeral to the Durham family. He obviously thought her contribution should be recognised. Was Archie Roach’s family afforded the same recognition?

This American recognition of the life of Archie was republished in The Boston Globe.

When Archie Roach was 3 or 4, welfare officers came to take him away from his family in southeastern Australia. His aunt tried to scare them off with a gun, and his cousins tried to hide him under a pile of leaves. His mother wept; his father came running in from the fields. His memories of that moment were scattered, he said, but eventually he was carried away on a police officer’s shoulder, told that he was leaving for a picnic.

When Archie Roach was 3 or 4, welfare officers came to take him away from his family in southeastern Australia. His aunt tried to scare them off with a gun, and his cousins tried to hide him under a pile of leaves. His mother wept; his father came running in from the fields. His memories of that moment were scattered, he said, but eventually he was carried away on a police officer’s shoulder, told that he was leaving for a picnic.

Mr. Roach was part of the “Stolen Generations,” the tens of thousands of Indigenous Australian children who were forcibly removed from their homes under government assimilation policies that lasted into the 1970s. As an adult, he struggled with alcoholism and homelessness, sleeping on the streets of Sydney and Melbourne while trying to reconnect with members of his family. He spent time in prison and in hospitals, suffering seizures that doctors linked to his alcohol abuse, and he attempted suicide while trying to dry out.

Music helped ease his pain. “It gave me something to fill the gap left by drinking,” he told People magazine. With his husky baritone, gentle guitar playing, and poignant lyrics about family, love and politics, he became one of Australia’s most renowned singer-songwriters, raising awareness of the Stolen Generations through his debut single, the 1990 ballad “Took the Children Away.”

“This story’s right, this story’s true; I would not tell lies to you,” he sang. “Like the promises they did not keep, and how they fenced us in like sheep. They said to us, ‘Come take our hand,’ set us up on mission land. They taught us to read, to write and pray.

“Then they took the children away.”

Mr. Roach was 66 when he died July 30 at a hospital in Warrnambool, Victoria, on Australia’s southeastern coast. His death was announced in a statement by his sons, Amos and Eban, who gave permission to use his name and image. (For cultural reasons, many Australian Indigenous people do not use a person’s name and image after death.) They said Roach had a “long illness” – he acknowledged struggling with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – but did not cite a specific cause.

A senior elder of the Gunditjmara and Bundjalung people, Mr. Roach was a leading advocate for Aboriginal communities, working with Indigenous children in juvenile detention centers and developing educational resources to help students learn about the Stolen Generations. The mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was “as much a part of Australia’s history as Captain Cook and Burke and Wills,” he told the Guardian in 2020, referring to British explorers who helped map the continent.

“We still need to own the whole history of this country and be honest and courageous,” he said. “It’s the only way we’re going to move on.”

Mr. Roach drew on American country, soul, and gospel in his music, releasing 10 studio albums and opening for artists including Billy Bragg, Tracy Chapman, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, and Paul Simon. But he remained best-known for “Took the Children Away,” which he wrote in the late 1980s, a few years after historian Peter Read started using the term “Stolen Generations” to describe the forced removal of Indigenous children from their homes.

“It is a landmark,” the Melbourne Age wrote in 1990, shortly before the release of Mr. Roach’s debut album, “Charcoal Lane.” “Quite apart from its place in Aboriginal history, it is a great Australian folk song, perhaps the greatest since ‘The Band Played Waltzing Matilda.’ “

When Mr. Roach first started playing the song, audiences were dumbfounded. “I had goose bumps and the hairs went up on the back of my neck as he sang it, to dead silence from the audience,” singer-songwriter Paul Kelly told the Guardian, recalling a 1989 performance by Mr. Roach in Melbourne. “He finished the song and there was still dead silence. He just stood there for a minute, and there was still silence.

“Archie thought he’d bombed, that everybody hated it, so he just turned and started to walk offstage. And as he walked off, this applause started to build and build and build. … I’d never seen it before – people were so stunned at the end of the song that it took them a while just to gather themselves to applaud.”

Five years after Mr. Roach recorded the song, the Australian government launched a national inquiry into the Stolen Generations. It found that from 1910 to 1970, as many as one in three Indigenous children – many of mixed white and Aboriginal descent – were removed from their communities and taken to churches and foster homes, under the premise that a Western upbringing was more humane. Many of the children faced physical and sexual abuse, according to the inquiry, which likened the forced-removal policies to genocide.

After more than a decade of campaigning by Mr. Roach and other activists, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued an official government apology in 2008, acknowledging what he described as “a great stain on the nation’s soul.” Last year, Australia’s government agreed to pay about $280 million in reparations to survivors taken from their families.

“For years I’d walked around with this burden, not just of being removed, but of who I was removed from: my mother and father,” Mr. Roach told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. in 2018. “It was like I was carrying them around with me for years, on my back. When the apology came it was like the weight shifted and I felt light. To me it was like they were set free – Dad to return as a red-bellied black snake, and Mum to fly away as the wedge-tailed eagle,” a central figure in Aboriginal mythology.

Archibald William Roach was born in the rural town of Mooroopna, Victoria, on Jan. 8, 1956. One of seven children, he was living in Framlingham, not far from where he died, when he and some of his siblings were taken to a foster home. Officials tried to westernize him, including by attempting to comb his hair flat, and falsely told him his parents had died in a house fire.

Mr. Roach was adopted by Scottish immigrants in Melbourne, whom he described as kind and loving. But “there was always a restlessness in me, like a fault line waiting to rupture,” he recalled. Around age 14, he got a letter from a little-known sister, Myrtle, telling him their mother had died the previous week. He left home and spent the next 14 years searching for information about his past, eventually reuniting with two sisters and other relatives.

As a homeless teenager in Sydney, he met Ruby Hunter, a fellow Aboriginal musician who had also been taken from her family. They became musical partners, got married and referred to each other as “Dad” and “Mum,” terms of affection that they used in the absence of their birthparents.

By the late 1980s they had formed a band, the Altogethers, and moved to Melbourne, where Mr. Roach’s performance on a local television show attracted the attention of guitarist Steve Connolly, who played with Kelly’s band the Messengers. Together, Kelly and Connolly produced Mr. Roach’s debut album, which won two ARIA Awards, the equivalent of an Australian Grammy.

Mr. Roach said he was initially uncomfortable with the spotlight, and for a time he considered quitting music. He continued after receiving encouragement from Hunter, who told him, “It’s not all about you, Archie Roach. How many Blackfellas you reckon get to record an album?”

His later records included “Jamu Dreaming” (1993), “Looking for Butter Boy” (1997), and “Tell Me Why” (2019), which accompanied his memoir of the same name. When the coronavirus pandemic forced him to cancel what was supposed to be his last concert tour, he sat down at his kitchen table and rerecorded the songs from his first album, releasing the new version as “The Songs of Charcoal Lane” (2020).

Information on survivors was not immediately available. Hunter died of a heart attack in 2010 at age 54, and Mr. Roach was still grieving her loss when he suffered a stroke that left him temporarily paralyzed on his right side. The next year, he was diagnosed with cancer, which caused him to lose half a lung. Still, he continued to perform, aided by supplemental oxygen.

He often said that each time he played “Took the Children Away,” he let go of a little pain. “I still feel the pain, every day,” he told Time magazine. “Sometimes it threatens to engulf me. But I’m not going to let it destroy me.”

Eventually, he said, that pain would be gone for good.

To complete the week of black crepe, now there is also Olivia Newton-John dead on 8 August. All in a week gone! The offer of a State Service was dwarfed by the public grieving in America fuelled by the various media reminiscences and her protean interests beyond the entertainment world. The memories and obituaries for her easily surpassed the other two. Yet each of them represented a facet of a Victorian childhood, albeit briefly, and as such in the death a reminder for me of the ballad rendering of:

“When I’m feeling sad

I simply remember my favourite things

And then I don’t feel so bad.”

I know this Twitter did not emanate from Prince Rupert

Republicans now want to abolish the FBI, CIA, IRS, Dept of Ed, impeach the President, VP, DHS Sect and AG, put the NIH Director in prison, and it’s only Tuesday.

Mouse Whisper

Reflecting on The Salon of 1846, I mentioned that I wanted to see France before I die. My friend, Rosemary, looked at me sagely and said I must have thyme on my paws. Next morning, pinned to my mousehole door, was the following:

“Brown rats and roof rats were eaten openly on a large scale in Paris when the city was under siege during the Franco-Prussian War. Observers likened their taste to both partridges and pork.

According to the “Larousse Gastronomique”, rats still are eaten in some parts of France. This recipe appears in that famous tome. “Alcoholic rats inhabiting wine cellars are skinned and eviscerated, brushed with a thick sauce of olive oil and crushed shallots, and grilled over a fire of broken wine barrels.”

Fortunately, I am very abstemious when I go to France.