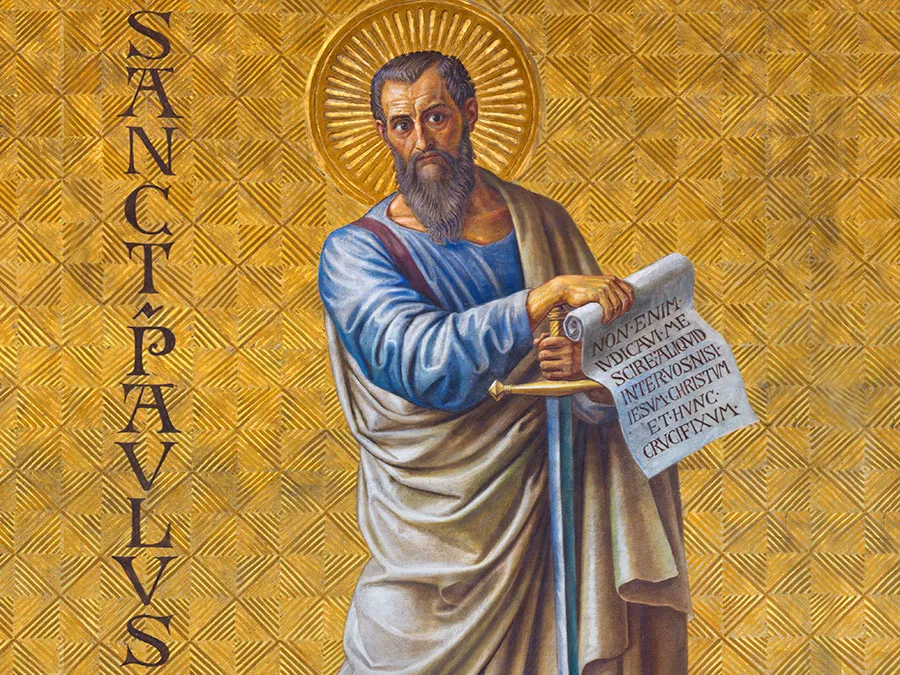

My elder son is called Paul.

He was named after St Paul. It caused some consternation on one side of the family. Where did that name come from? “Bit Catholic” was one typical comment. Belying this comment, in Sydney there are 10 Anglican St Paul’s in addition to the Anglican St Paul’s College at the University of Sydney and only three Roman Catholic St Paul’s. In addition, there are two Lutheran Churches of that name, and shared names with St Anthony in the Coptic Church and with St Peter in the Russian Orthodox Church. Thus, recognition of St Paul is eclectic, but strongly Anglican in the Diocese of Sydney. I’m sure he would be bemused about the naming rights.

To me, St Paul was integral to the propagation of the Christian faith – the original missionary. But he is also the traditional convert who become far more wedded to the Christian cause as he did because of the fateful episode that the then Saul, a violent Anti-Christian, had that one day on the road to Damascus. I recognise that converts are often weird and fanatical but driven. In St Paul’s case, his conversion was so completely a positive event for the Church which his subsequent actions confirmed. Yet Paul did not work alone. He had supportive people by his side, for instance, Barnabas and Silas, when he made his three major tours through the Mediterranean countries. Even St Luke was present to witness his travels. St Paul attests to that in his second letter to Timothy, where Luke seems to be Paul’s only companion.

He was “a bloke” – so far from some of the modern Church ministers of religion, where raiment and the arcane trumps everything. No, he would have eschewed such frippery, despite him being painted as some balding bearded man in flowing robes. He was the archetype worker priest. He was plainspoken and yet some of his words have been so often repeated that their force is lost as a cliché.

How many times has “Through a glass darkly” been quoted; but what an image such words provoke!

St Paul was undoubtedly authoritarian – always telling the people to whom he wrote his letters what to do – probably inciting dread in the early Christian community. “Paul is coming next month. We better clean the house.”

St Paul was undoubtedly authoritarian – always telling the people to whom he wrote his letters what to do – probably inciting dread in the early Christian community. “Paul is coming next month. We better clean the house.”

He was a misogynist, but in his defence, it reflected the mores current at the time. In other words, he was not some alien person, who floated round the Mediterranean as some ethereal figure without sin.

That was the great quality of this Man – a person driven by a desire to change the world by word not sword. He projected a powerful message; and as I have always said I define my own ideal companion as a person whom I can trust but not necessarily a person who will always agree with me. Those I suspect, because if one can be as disagreeable as St Paul was on occasion, one must generate animosity even if, as can be detected in the Pauline writing, there is compassion underpinning his interpersonal relationships.

My reaction to this restless man is not unique. Other authors have noted his missionary zeal. Essentially these words in his Letter to the Philippians reveal a man, who has a firm moral code, to which he can be called to account.

Finally, brethren whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there to be any praise, think on these things.

Preceding this call for meditation are those words which have become the conventional benediction for many Christians.

And the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.

And that about says it all, except to mention that recently I prayed to St Paul for his intervention, and my prayers were answered. I have always found comfort in the above words which I whispered to myself on this occasion.

I Must Report

My grandfather may have described himself as a mercer rather than working in schmutter aka “the rag trade”. Notwithstanding one must call it as it is – a man in a bowler hat, detachable wing collar, handmade shirts and suit, bow tie, waistcoat with fob watch and of course spats. (Memoirs of a watcher over a Toorak stuccoed stone fence)

There are two meals that stick in my memory. Given that I have regularly devoted parts of my blog to personal observation, I thought it important for me for me to write up these two meals. They did not occur overlooking the sea or high on mountain tops; nor were these meals in elegant places with silver service and the light glinting on crystal glasses.

The first was sometime in the 1940s when there was still rationing in place. As I have written about my father’s nomadic need to travel before, once he had a car, he would often try to get away for a weekend with my mother and myself. There were no motels and therefore we depended on the availability of local hotels to have a bed. Towns had the Railway Hotel and the Commercial hotels to reflect where they were built and who inhabited them during the week. And Strathmerton did not disappoint – there was a low-slung Railway Hotel. Strathmerton was a small dairying town just south of the Murray River on the edge of the Goulburn Valley.

Remember, this was a time before credit cards, and payment was restricted to cash or cheque.

Now why do I remember this place. In the morning, the breakfast was something I had never experienced: sausages, steak and eggs, and the bacon. I still can picture those rashers of bacon. The toast was thick, warm and buttery.

This was a time when rationing of some food items was still in place, meat and tea. Eggs, milk and particularly butter were in restricted supply – sugar was removed from rationing in 1947. I had only experienced brown sugar, so white sugar was a novelty. Chocolate was non-existent, except in Laxettes.

This was a time when rationing of some food items was still in place, meat and tea. Eggs, milk and particularly butter were in restricted supply – sugar was removed from rationing in 1947. I had only experienced brown sugar, so white sugar was a novelty. Chocolate was non-existent, except in Laxettes.

None of these restrictions meant much because, until I was six, I had never lived in a country not at war. When I stayed in the country then with my aunts there were eggs and milk. I did not like milk anyway. But eggs … and Marmite; that was something else.

This breakfast was so different – a full on delicious Australian breakfast. I have always enjoyed big breakfasts since, but unfortunately in growing older self-rationing becomes de rigeur.

The second memorable meal came in the second year after graduation. It was the first time we had a car. I was married and our first child was on his way; yet we had no car. I had a job at Geelong Hospital, but my wife was working as a post-graduate research scholar at the University of Melbourne. My mate, Don Edgar had been recently ordained and he had a locum posting in Tallangatta in North-east Victoria.

We had not seen him for a while, and he invited us up to stay with him. But we could not have chosen a worse night to drive. It was a time when a car may have had a heater but was not air conditioned, where the car did not have the safety features of the modern cars, and the Hume Highway was still mostly two-lane. The weather was bitterly cold, it was winter, and at times we encountered sleet.

I remember bringing a bottle of Moyston claret to drink with Don if and when we got there. In a time before mobile phones, and a disinclination to venture out into the weather to ring him from a phone box, we pressed on.

Tallangatta is a village on the shores of the Hume Weir, which had been rebuilt once the original township was sacrificed to be swallowed when the Murray River was dammed.

Once we arrived in Tallangatta it took us time to find where Don was living. Eventually, we saw the light in the window, and there was Don at the door, appropriately rugged up.

He ushered us inside, where he had built a roaring fire. The residence was basic but coming in after such a stressful drive it was a palace. The claret was warmed; the soup was robust, and the bread rolls were fine. This was almost biblical, but fish was not on the menu.

A Forgotten Observer

They were familiar not only with the grass seed they so laboriously gathered and ground into flour, but with many bulbs and herbs and underground nuts and tubers also, the native carrot and native onion, the edible yam, which is so like our floury potatoes and a much sought-after food all over the continent. The quandong, too, sometimes called the wild peach, which is good eating when raw and makes a tasty jam – how easily could a tribe have planted practically unlimited number of such fruit-trees! Yet these things they never once thought of growing and cultivating during all the thousands of years they have been struggling for life in this country. And yet they carefully explain to their baby daughters all about the yam-vine from its “beginning” to its “end”, the soils the different varieties grow in, and the conditions and seasons necessary for its growth. They even explain that a few must always be left, so that with the next rain others may grow up. Yet apparently, they have never thought of planting one.

In the coastal and more favoured areas of the continent, if they had thought of such a thing they might have said, “Everything grows in plenty for us here, in a good season anyway, then why should we toil to grow it?” But over the far greater area of the continent, with its recurring harsh times, that they never thought to improve their food supply by growing edible seeds and plants and fruits is a puzzle in the progress of human life.

Ion Idriess was a prolific author, writing 50 novels about this country of ours. He has lost the popularity he once had, but for a man born in Sydney in 1889 and dying 90 years later in Sydney in the intervening years he was very busy. There was an extraordinary litany of achievements through various occupations – opal, tin, gold miner, buffalo and dingo shooter, shearer, boundary rider – in diverse parts of Northern Australia. He encountered many Indigenous people, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

His perspective in the above has, to my mind, never been introduced into the confused debate of whether the Aboriginal people ever embraced the agricultural revolution.

His writing at times makes one react as if he was scratching his fingernail across a blackboard. The use of “Stone Age” as a description is not acceptable, because clearly the Aboriginal people are not. The use of inappropriate language in one context does not destroy the validity of his interpretation of some of his observations. In the face of these observations what sophistry would Bruce Pascoe use to justify his thesis? What I have found irritating in all this debate, given all the literature available, is how much has been ignored, such as that of Idriess.

Idriess, because of his times and his language in relation to Aboriginal contact, might jar. Nevertheless he had a clear eye, and in days before the taboos were well articulated said he was able to “bribe a ‘witch doctor’ ” into showing his sacred objects. Again, the Aboriginal “witch doctor” may have double-crossed him about the nature of what he revealed, but the observation may have been just as valid.

It is just that I once was given the privilege of seeing sacred objects, which only men are allowed to see. His observations did not tally with mine. However, the diversity of these individual tribes should never be underestimated, and every time I look at my collection of paintings and other artefacts, it just reinforces the diversity among these Aboriginal mobs. Idriess travelled extensively and that is why his descriptions ring true. He was an observer, admittedly culturally insensitive, but nevertheless historically valuable in being able to describe situations that now are hidden by cultural taboos, whether confected or not.

One of Idriess’ strengths was that he effortlessly mingled with Aboriginal people, but never “went native”. Like me, he did not have the genes which had been coursing through Aboriginal people for thousands of years. I retain the ultimate regard for the heritage of Aboriginal people.

If there were to be an honest appraisal of the actual achievements not the constant blame as if it were totally one-sided; the persistent talk without action (so-called “conversations” in different exotically attractive venues across the continent, also a form of expensive, diversional therapy for whitefellas able to afford the entry and travel costs or paid courtesy of the government), then I would without question vote “Yes”.

There is so much humbug floating around.

Try a “conversation” in the Tanami desert in January, Prime Minister.

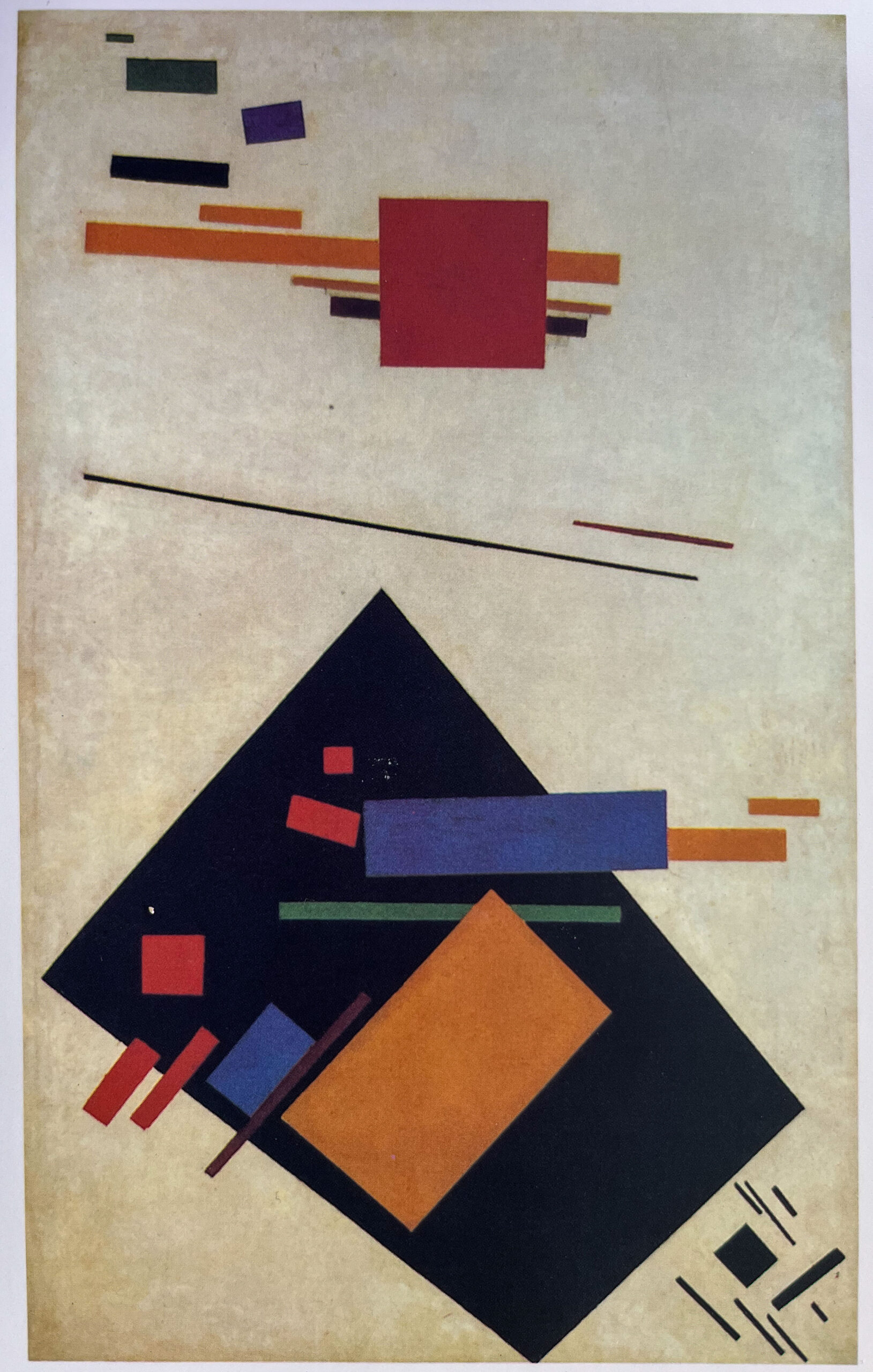

Malevich – Remarkable Painter

The Athletes also concerns the artist’s own metaphysics, which are quite distinct from that of the stablished church. He has erased all particular detail in order to bring to the fore his vision of humanity’s connection to the cosmos …The removal of facial features and the lowering and flattening of the horizon graphically emphasise the figures’ tenuous connection with the earth. Their feet on the coloured ground, their heads in the infinite white heavens – their half-white heads – all express the dualistic nature of natural beings and their evolving destiny.

I was sorry that we were unable to visit the Vermeer exhibition this year in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Vermeer, together with Magritte and Malevich, are the three painters whose exhibitions, in normal circumstances, I would have made every effort to travel anywhere to see.

We did so in 1998 for the exhibition in Brussels to celebrate the centenary of Magritte’s birth. I have written about the hoops we had to jump through to gain entry into that exhibition. This escapade has stuck in my memory; it was a good story, especially as it ended up in the “happily ever after” box.

But what of Malevich, the third of “my must see” painters?

I stare hard at the figurine of one of the Athletes in the painting by Kazimir Malevich. I purchased the figurine as a memento of the Malevich exhibition. It was the one with half the head coloured red the other side white. The rest of the figurine is a mixture of red and black. It doesn’t look like an Athlete, but I read the explanation, with which I headed this piece. I also have a coffee table book which shows most of his paintings, as well as a set of Malevich postcards and a large poster titled The Carpenter, which was painted and reflects very much the style he used in The Athletes.

I stare hard at the figurine of one of the Athletes in the painting by Kazimir Malevich. I purchased the figurine as a memento of the Malevich exhibition. It was the one with half the head coloured red the other side white. The rest of the figurine is a mixture of red and black. It doesn’t look like an Athlete, but I read the explanation, with which I headed this piece. I also have a coffee table book which shows most of his paintings, as well as a set of Malevich postcards and a large poster titled The Carpenter, which was painted and reflects very much the style he used in The Athletes.

Kazimir Malevich, the man born near Kiev in 1878, spent most of his life in Russia. His professional career was counterpointed by the 1917 October Revolution and the growth of the Soviet Union. He died in the then Leningrad in 1935. Only on two occasions did he leave Russia, having been given permission to go to Poland and Germany in the 20s. Most of his works therefore are retained in Russian Galleries, but there was an exhibition of his paintings a decade ago at the Tate Gallery in London.

He was the central figure in the Supremacist movement and there is a great force in his paintings – notably in his originality in style. He is the one painter, whose work I could gaze at for hours. For most galleries I just breeze around absorbing image after image without stopping for long in front of each work. Yes, I admit Guernica, Picasso’s painting makes me want to sit and have a longer look. Otherwise, Picasso does not provoke the same level of interest as Malevich; Picasso had this great facility to dash off a figure with an almost impeccable facility, but they do not connect emotionally.

But Malevich, with his ability to break form down to component and colour, appropriately and deftly lays a beautiful tableau. Even the definition of the principles of Suprematism to reject any form of realism and paint simple shapes such as the circle, square and triangles forces one to recast your view of the world. They also used these shapes as vessels to explain and communicate themselves to the public or the viewer without any use of words or typography. There was limited use of colour in the palette with only basic colours such as red, yellow, blue and green, in addition to white and black.

This colour minimalism is shown by a series of diagrammatic paintings, with anonymous numbering of most of them. What I find fascinating is they seem to be architectural drawings if viewed casually, perfectly outlined rectangles, circles, squares – the architect of the cosmos. The juxtaposition of the components seems to be in harmony; I frankly don’t know why and thus if I try to articulate what they mean I’ll end up in a tangle of words. There is one of these Supremacist works which he links to an aeroplane taking off. The reference point to this are several red lines – he would deny that the red line was the horizon, just a guide to his black and yellow rectangles and oblongs, the plane about to fly off the page.

The solid black painting is the signature of the Supremacist movement – just a pure Black Square. As though in a dark place we are seeing a lunar eclipse at the time when the Moon is closest to the earth (perigee), but paradoxically The Black Square is boxed in by a frame, and it is always hung in a corner of the gallery where normally in the Russian household an icon is hung. I can see what Malevich is trying to do, but that painting is easily mocked by others, including the Australian painter who replicated the Black Square by inserting a combination lock into his version of the Black Square. It brought contemplation of this Malevich work back to Earth.

On Malevich’s gravestone there is a Black Square, with a generous white concrete border.

Malevich went through post-impressionist, cubism, fauvism phases. After his Supremacist period, he reverted to folk artist primitivism, which persisted up to his death. Given how uncertain life was under Stalin, in a period where purges had continued that Russian propensity for pogroms, Malevich may have gone back to folk art as a Survival phase, but he did not live to the Great Terror of 1937. Yet one of the enigmas surrounding Malevich is his sudden cessation of Supremacist painting and reversion to folk art. Why? Perhaps he could not progress his ideas any further.

In the end, if you asked why I so am attracted to Malevich that once I was prepared to travel across the world to see a retrospective, it is his unique representation of the level of affinity and appreciation of what are essentially spatial juxtapositions, so clinical and technical; yet so original … and so difficult to articulate.

Mouse Whisper

Wrestling with concept of Suprematism?

A plane of painted colour hung on a white sheet of canvas imparts a strong sensation of space directly to our consciousness. It transports me into an endless emptiness, where all around you sense the creative nodes of the Universe.” – Kazimir Malevich.

To be read in conjunction with “Untitled (Suprematist Painting) painted in 1915 now hanging in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.