“Less than 10 percent of the 280,000 species of flowering plants produce blue flowers”

I love blue flowers. I remember there were masses of hydrangeas growing in Victorian Gardens. They were blue, pink, white and variegated. First cultivated in Japan, they are found worldwide in the wild, without there being a single source from which they first grew. There are even Australian hydrangeas with small cream flowers vaguely resembling jasmine and found along streams in NSW and Queensland.

They are a garden flower; brought indoors they are somewhat “crowded house”. They need a big canvas upon which to show off. Living in a maisonette, small rooms just tended not to be the best place to display these flowers. I was told that if you put copper filings in the soil, there would be hydrangeas blue; and if an iron nail is put in the soil, hydrangeas pink.

This formula was not true, truly mythical. In acidic soil with aluminium sulphate as the key component, in a temperate climate, then the blue hydrangea blooms. Quite the opposite of the litmus test, which always records acidic soil as pink.

The scientist’s quote above says it all. Flowers are uncomfortable with blue pigments. Yes, the Japanese have created a blue chrysanthemum by genetic manipulation. Of the few true-blue flowers, if you discard the intrusion of the various shades of red and indigo, all are a delight – well at least for me. If you treasure these flowers then one of the times to be in England is in early spring when bluebells come out in a riot of colour for a few weeks and then retreat, leaving the lush greenery of a well-watered landscape bereft.

Cornflowers are the spiky kid on the block. They have their day at the Spring Racing Carnival in Melbourne when they are the flower of Derby Day. With their small confident upright stance, they make an excellent lapel adornment.

A symbol of hope, the cornflower is the national flower of Germany – and the basis for Prussian blue. Its name was derived because it grew in the wheat, barley and rye fields. There is an Australian native cornflower, but the flower is different in configuration, but given the cornflower has the feel of the Australian everlasting, our version is found in arid regions.

But my favourite is the delphinium, with its tower of blooms. There are various shades of blue but given there are apparently 300 different species and apparently they can be either merged with larkspurs or they remain close relatives, this flower from the high mountains of Africa and Europe is my favourite blue, because there is more than one shade of blue.

They tend to have a brief expression of glory. As one writer put it: Sadly, the flowers were short-lived. And being tall with a heavy abundance at the top of each stalk, all it took was one heavy rain to knock it over and send the flowers sprawling all over the grass. I enjoyed it while I could, and after my first summer, I sunk a tall rose climber into the ground to support the top-heavy stalks and protect them from heavy rain.

When I see the delphinium begin to drop its flowers, it should be realised that they are toxic. In fact, all parts of the plant are toxic – the active ingredient being the neurotoxic effects in the flower’s diterpenoid alkaloids.

So be wary if your herbalist friend offers you delphinium tea.

In explanation of my blue reverie, I’m very visual – how could I ignore the blue hydrangea!

The War of Jenkin’s Ear

Well, we know what happened to Robert Jenkin’s ear. It was sliced off in a confrontation between Jenkins, who was the captain of the British brig Rebecca, and the Spanish coastguards who boarded his ship off Cuba in 1731. Eight years later it was the casus belli for the British Government to declare war on the Spanish. Jenkins had appeared before a Parliamentary Committee to tell his story and allegedly show the Committee his severed ear. Shock, Horror – and the British declared war on Spain in 1739.

It was a desultory affair confined to the Caribbean, except in British eyes the capture of the Portobelo fortress by Admiral Edward Vernon (the man incidentally who gave us the word “grog”). Portobelo was a Spanish possession on the Caribbean coast of what is now Panama. It led to much rejoicing and inspired the writing of “Rule Britannia” and the name has been immortalised in the name “Portobello Road” in both London and Edinburgh. This war ended up merging into the European dust-up, the War of Austrian Succession. In fact, the name was coined in 1858 by the historian Thomas Carlyle; but the name has persisted.

Now the dilemma of Trump’s Ear. The world has moved on. Trump has had a pillow completely obscuring his right ear at the Republican convention. Now Trump said he was shot. The media have taken that as gospel; and even the sceptics say the bullet grazed his ear. The gunman had a high-powered rifle sufficient to kill one of the spectators and injure two others. The gun was not a pop gun.

I have looked at the right ear in the multiple photos available. He has a bloodied right upper helix of the ear and what appears to be clotted blood in the triangular fossa. A medical opinion later said it was a two cm cut.

What surprised me was there seemed to be no indication of the aural cartilage having been damaged, but then maybe the angle was distorted. However as one who has seen and sewn up a cut ear, it is not a trivial exercise. There just did not seem to be any damage in Trump’s ear. A bullet striking the ear, however you measure “grazing”, would have left its mark on the ear cartilage.

Turning to the Trump face just after he emerged from beneath the lectern, there was a smudge over his right mandible, but what intrigued me were the two thin lines of blood which seem to arise without relation to the bloody ear. They are thin straight lines which converge on his lips. The lower line seems to defy gravity by starting at the base of his mandible with no discernible source and moving upwards. Somebody might explain it, but then it was all too trivial. Trump said he was shot and that man with his history of fable telling must be believed.

And hallelujah, if you removed the ear dressing, the ear would appear normal – just a God given miracle.

Later, his controversial doctor, Ronny Jackson, stated that Trump sustained a two cm wide wound from the track of a bullet “that extended down the cartilaginous surface of the ear.” No sutures were required for Trump’s wound, Jackson said, but “there is still intermittent bleeding requiring a dressing to be in place”.

What an amazing bullet! It initiated a two cm cut without damaging the cartilage? I liked the last bit about the intermittent bleeding. Is Trump on anticoagulants?

We await the water stroll, or before that intercession by His Buddy, will Trump’s failed assassination just merge into the War of the Trump Succession?

Paper, Paper Everywhere and not a Thing to Show for It

We’ve been clearing out boxes and boxes of papers – a concentrated episode of nostalgia. Some files are just thrown out, because the link with that subject matter was tenuous and I wonder why I kept them. Yet there are the others, which attract both my amateur archivist interest and nostalgia at the same time. They are files which showed something in which I was involved.

Nevertheless, more than a passing comment, those committees or matters on which you have the minimal involvement of the passing observer are far too common. It is one of the pitfalls of trying to involve every person or organisation that those in authority think are relevant or politically important. Then they either do not turn up with or without an apology or the representative attends, contributes nothing, is basically unprepared and then at the next meeting a different representative attends without any real interest, and at what cost. So much “shuffling the sand” and getting nowhere.

I was asked to undertake a Rural Stocktake to ascertain what should be done to encourage doctors to go to the country. The then Minister of Health, Michael Wooldridge, had as one of his priorities, improvement of rural health. One of the tangible expressions of this was the improvement in the rural medical workforce, which in turn would flow onto improvement in the health professional workforce, including the Aboriginal health workers. Whether this could be construed as a “trickle-down” phenomenon, or a coincidence, was a question which I believe after all these years relies on a successful multi-professional approach. This is difficult to achieve because each profession, because of regulation and tradition, will be ever-present, especially where conflict between the various entities is provoked.

The original terms were that it be a three-month consultancy, that there would be a committee to help me and I would have the Department providing me with administrative assistance and at times one of the bureaucrats travelling with me. I was given an Optus phone, which in those days did not have enough rural coverage to be of any use. The Department would write the Report.

What happened? The consultancy was extended for six months; the committee might have met once at the very start. The makeup conformed to what I have said about Committees. After I had completed the Australia-wide consultations which absorbed the whole six months, I wrote the Report, which took three months for which I did not get paid. But it didn’t stop the politicians questioning the amount of money my company was paid. Some of them were taken aback when I called them directly and asked the basis for their concern. Not much came of that except mumbled responses.

The problem was that at that time, I was close to the Minister, which attracted the normal set of “maggots” who seem to think everything is rotten in such a relationship, only to find out that there was nothing there. Our affinity rested on the desire to get things done.

In addition, the Secretary of the Department, Andrew Podger, whom I did not know previously, was extremely progressive and fitted into the Wooldridge agenda. When Wooldridge retired prematurely, my view was that it was bad for his unfinished agenda and not particularly good for himself personally. But that is life.

The Stocktake involved me travelling around Australia, but I had the advantage of already having been involved in rural health issues really since the first week after medical registration, even before I started my first year internship. Then with my then wife, who had also just graduated, we undertook a locum in Birregurra in Western Victoria. That was January 1964.

These days doing such a locum just after graduation is debarred. For God’s sake, one has gone through five or six years of a medical degree, and the graduate doctor cannot practise unencumbered. It is one of those expensive unproven exercises that are imposed by authoritarian administrators without any real evidence. However, there is a more insidious reason and that is in the pursuit of private practice, teaching recent graduates is relegated down the list of priorities. Has anybody calculated the cost of this? No, because it is easy to bluff politicians with words like “safety” and “malpractice”, although the doctors do not retain the omniscience they once had.

Wooldridge agreed with the major recommendation of the Stocktake to establish a series of rural clinical schools linked to universities which already had a medical school. I reported in March 2000. Twelve months later, in anticipation of the 2001 Federal Budget, Wooldridge announced in Bairnsdale the creation of rural clinical schools, the Bairnsdale site being part of the Monash rural clinical school. Funding was provided for another seven sites. It was an extremely quick adoption of the Stocktake recommendation.

At the time the Universities with medical schools were enthusiastic. With most of them I had extensive consultations, which were also facilitated through other links. Wooldridge was able to fund the rural clinical schools directly through his Health budget rather than through Education where the central administration of most Universities generally skimmed off a percentage of this funding for “God-knows-what”.

The aim was to train a cohort of medical students in their clinical years in a rural setting. For instance, the University of NSW Rural Clinical School would have nodes at Albury, Wagga Wagga and Griffith. One of the ways the Stocktake was crafted was get the country areas and the universities positive. As those who are familiar with rural Australia know, there are intense rivalries (e.g. Albury vs Wagga Wagga). It is one of the problems of rural living and, as a rule of thumb, the closer the townships often the fiercer the rivalry, which makes collaboration a tricky business.

Then within each of the townships, there is conflict between professions, and this needs some degree of massaging. Nevertheless, there was a need to involve general practices as teaching sites. There was already a registrar training program where the Government funded the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). The problem was while there were good teaching practices, many used their registrars as “mules” just doing unsupervised consultation on government funds – in effect “double-dipping”. The entry of the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM) with their initiative of the “rural medical generalist” coincided with the approval of the medical School at James Cook University in Townsville, with subsidiary campuses at Cairns and MacKay. Ian Wronski, who was a leading academic with long experience working in Northern Australia, particularly the Kimberley, was the driving force behind the initiative; I prepared the submission and Wooldridge approved it. The process was open, the arguments persuasive.

Wronski, in pursuing this agenda, not only created a rural medical school in the tropics but also saved the University which had built up a reputation in marine biology but very little else. Wronski then developed schools of dentistry, allied health professionals, including nursing and veterinary science.

The other part of this approach to rural health had been the creation of University Departments of Rural Health (UDRH). The first two sites – Broken Hill and Mount Isa – were chosen because of remoteness, because the aim was to have a multicultural training centre in population health. The concept was new, but I was able to obtain locally-based allies in both cities.

The UDRH program has been successful in the number which have been created (12) but they have strayed from the original intention of the program to integrate population health into clinical practice. However, the progression of the program has been hampered by the failure of the Rural Health Commissioners to progress the agenda and so the program still has limitations in its ability to satisfy its original aim.

The Hanging Participle

John Funder AC is a sage and probably would be happy to hear himself described as a polymath. He is the father of the best-selling author, Anna Funder.

Jesuit-schooled, Funder is one of the few who took the traditional Classics whilst at school, Latin and Ancient Greek. An excellent orator, Funder usually was able to navigate the shoals of academic research and university politics with ease. We knew one another from shared university and post-university experience, never close but generally experiencing entertaining interactions when we did.

But I was surprised one day to receive a note, commencing as always charmingly:

Dear Beastie,

You’ve done it again. Not only is “The Best of Best” terrific as it routinely is, but the underlined sentence is now the benchmark for the floating (a.k.a. hanging) participle.

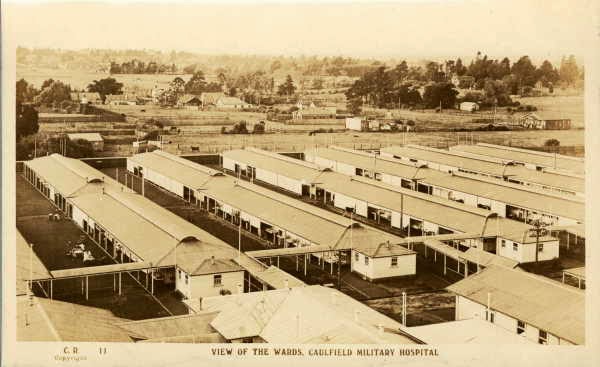

The underlined sentence occurred in an article where I was mentioning being at a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art honouring the Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto. The year was 1998, the centenary of Aalto’s birth, and for those unfamiliar, he was inter alia the original architect for the modern hospital, producing those characteristic airy flowing designs, so different from the forbidding Victorian hospital design,

The underlined sentence occurred in an article where I was mentioning being at a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art honouring the Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto. The year was 1998, the centenary of Aalto’s birth, and for those unfamiliar, he was inter alia the original architect for the modern hospital, producing those characteristic airy flowing designs, so different from the forbidding Victorian hospital design,

And the sentence over which Funder waxed lyrical: Wandering around the pictorial display of Aalto’s genius, interspersed with scale models of his various buildings, there is certain familiarity.

Well, at least I could sit down on my benchmark to recover from such a gust of praise.

Mouse Whisper

This would appear somewhat relevant to what is going on with the current Construction, Forestry, Maritime, and Energy Union (CFMEU) conflict with all the associated heavy-handedness.

This observation appeared in the Column 8 of the SMH some years ago. A reader wrote that he had seen a truck with what the writer described as a flamboyant sign: Rough as Guts Constructions. The number plate on the truck, YAH-HOO.

Also, when I was working for Repatriation Department, I assembled all the outstanding medical files, including the backlog, in less than a month. So much so that my supervisor told me to slow down. Instead, once I had no files to assemble in my in-tray, I went into the rooms where the medical files were kept, and with the enthusiasm of youth assembled the files of several high ranked officers not knowing if I was transgressing any regulation. In any event nobody stopped me. I was amused when I encountered what amounted to the brown hard back medical record. This was the venereal disease record, and there was no way this could be missed. It was an early introduction to my eventual medical career.

Also, when I was working for Repatriation Department, I assembled all the outstanding medical files, including the backlog, in less than a month. So much so that my supervisor told me to slow down. Instead, once I had no files to assemble in my in-tray, I went into the rooms where the medical files were kept, and with the enthusiasm of youth assembled the files of several high ranked officers not knowing if I was transgressing any regulation. In any event nobody stopped me. I was amused when I encountered what amounted to the brown hard back medical record. This was the venereal disease record, and there was no way this could be missed. It was an early introduction to my eventual medical career.

The Defence force spends somewhere in the region of $40m a year in recruitment of men and women to the army, navy and air force. Nowhere in the advertisements is the message, join the defence force to be killed fighting for your country. Rather, learn skills, enjoy yourself.

The Defence force spends somewhere in the region of $40m a year in recruitment of men and women to the army, navy and air force. Nowhere in the advertisements is the message, join the defence force to be killed fighting for your country. Rather, learn skills, enjoy yourself. The other perception of the Church is how ludicrous some of the regalia looks when placed alongside stated conservative attitudes. After all, look at the fancy dress of the church dignitaries and then fast forward to the forthcoming dress-ups for mardi gras by the queer dignitaries.

The other perception of the Church is how ludicrous some of the regalia looks when placed alongside stated conservative attitudes. After all, look at the fancy dress of the church dignitaries and then fast forward to the forthcoming dress-ups for mardi gras by the queer dignitaries.

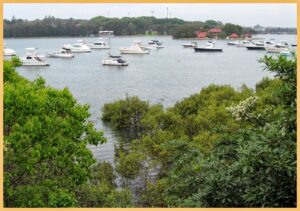

When I used to run the Iron Cove, the mangroves were there, but not to the height and extent as the mangrove forest now. It used to be stunted and did not exhibit its current lushness – rather it was a swamp bordering on the estuary, the water flowing tidally, and at ebbtide, it was a muddy swamp with just a thin cover of mangroves. Now it is different and given the mangrove so essential for water hygiene, maybe the underlying pollution will diminish.

When I used to run the Iron Cove, the mangroves were there, but not to the height and extent as the mangrove forest now. It used to be stunted and did not exhibit its current lushness – rather it was a swamp bordering on the estuary, the water flowing tidally, and at ebbtide, it was a muddy swamp with just a thin cover of mangroves. Now it is different and given the mangrove so essential for water hygiene, maybe the underlying pollution will diminish.