On the 9-10 May 2001, the House of Representatives met in Melbourne to celebrate the Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sittings. Twenty years on, only five of those who were sitting as Members that day are still members of Parliament.

On the 9-10 May 2001, the House of Representatives met in Melbourne to celebrate the Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sittings. Twenty years on, only five of those who were sitting as Members that day are still members of Parliament.

One is Kevin Andrews, a somewhat desiccated hangover in the Coalition, who is about to be consigned to “feather duster” status, after an undistinguished 30 years in Parliament and after losing preselection.

Warren Entsch and Bob Katter are from the wilds of Northern Queensland. Both have been able to ensure election without regard to any political affiliation. Katter is part of a dynasty, and both have fiefdoms. Intervention in any issue of national importance is incidental; neither is in a position to be national leader; and indeed, do not want to be so. They both want influence of their own choosing, even as they have become old men.

The other two who were there that day? Antony Albanese and Tanya Plibersek. Each has represented inner Sydney electorates for the Australian Labor Party for that period of time; in fact Albanese was elected in 1996 and Plibersek 1998. Frankly, I thought there would be more than just five, but these latter two are still very relevant to Australia as we move towards 2030.

Yet what have they done to move the needle towards ensuring a better life for Australia?

When Whitlam came to power in 1972, he gave Australia a mighty jolt. He had foreshadowed significant change during the vindictive years of McMahon and the alcohol-stained Gorton incumbency. “It’s Time” rang around Australia.

So dangerous was Whitlam to the bunyip aristocracy that eventually, with the connivance of the Royal household and the American security service, a coup was engineered in 1975 which led to Whitlam being sacked by a drunken popinjay called Kerr, dripping in the lard of an antique post and aided and abetted shamefully by the then Chief Justice Barwick.

However, the people showed very clearly that they were tired of Whitlam. I was a spectator in these exciting times because, whatever could be said of these years, Australia threw off its bunyip ossification.

What followed was instructive, and the fact that the current government is as bad as it has ever been has given me cause to reflect. The decade post-Whitlam saw some of the most important policy made at a national level which brought us from a narrow Poujardist, sectarian-ridden country to one where the economy and the social structures bloomed – until this past decade.

Howard, for all his conservatism and his unconscious comic talent, strangely was the last remnant of that age, during which the mood of the country reverted to that previous xenophobic jingoistic time.

Malcolm Fraser came to power in 1975 in a landslide, which could be interpreted as a rejection of progress, and he was then successively re-elected until he was voted out in 1983. Fraser was a “curate’s egg”. For instance, his approach to economic reform was that of nineteenth century Victorian protectionism. His attitudes here with the morning-suited Eggleton whispering in his ear, set back our progress a decade.

However, despite the whisperings, he did make a number of decisions that can be attributed to his government having worthwhile impacts. I have tried to think of what Albanese and Plibersek have accomplished given that they have held ministerial positions and been in Cabinet over the past decade.

The reason I am musing about this was the discovery of an article in the Guardian Weekly written 13 years ago. The title “Harpoons Down – Australia’s Last Whaling“. The last whaling hunt happened in 1978. The last whaling station was at “Cheynes Beach” near Albany, a city on the southwestern coast of Australia. It was closed that year. At the time, there was a great deal of concern expressed as to the fallout in that community; the normal talk about the loss of jobs and of a city under stress given its isolated location.

I remember visiting the station six years earlier when it was fully operational. When we arrived, the whales were being cut into huge slices. We weren’t worried about the smell. There is a lot of blood, but my children eagerly touched the body of the closest whale carcass.

My sons haven’t forgotten that experience since. People may abhor the slaughter of whales – whaling was so much part of our heritage as watching them has become today. My sons had grown up spending their holidays in Port Fairy, in a rubble walled stone cottage built in 1848. Port Fairy, together with other settlements on Victoria’s southern coast and the offshore islands of Tasmania, owed much of their origin to whaling. The cottage was named for Ben Bowyers, himself a whaler, who built it.

In April 1979 Malcolm Fraser pledged his government’s “total commitment to protect the whale”. It was said that he was heavily influenced by his daughter, Phoebe. Nevertheless, a total ban on whaling in Australia and the development of policy for the protection of whales further afield in international waters followed. For this, Fraser could claim that he had achieved a major change in Australian policy and attitudes.

The cessation of whaling did not convert Albany into a ghost town. I think of an ongoing prosperous city today when, across the Continent, there are coal mines dotted all along coastal New South Wales. Yet Albanese and Plibersek, if not cowering under the assault of the coal mining industry and their union collaborators, are certainly not indicating a co-ordinated program to reduce coal mining either.

That is the worrying problem. That if Australia is faced with ridding itself of a corrupt government prolonging the moral desert, do we need a timid alternative with a blank record dedicating itself for minimising change, thus retaining a compromised bureaucracy with a carousel of consultants looting the country? Moreover, where is the plan to rid the coastal strip from the Illawarra to the Hunter of coal mining? After all, I am old enough to remember the despoliation of the beaches in the same area near Newcastle by sand mining and the bleat about loss of jobs. No sand mining in the Myall Lakes now. Loss of jobs? Not that you ever know whether these sand miners were ever reduced to penury.

Do we trust a government led by any NSW politician of any political colour? When last in power in this State, the ALP government was full of corruption, as we the community are being reminded as we watch the fall out still be played out in the courts.

More spine, Albo. Dig up the “goat tracks”, as Eddie Obeid so colourfully described the trail of lobbyists and hucksters wandering to and around the Parliamentary Executive Offices!

Additionally, a small piece of advice, get yourself or at least one of your trusted lieutenants to become fluent in Health as Neal Blewett did. The lack of appreciation that Health has a separate language leaves any politician such as Plibersek at a disadvantage. Certainly it did when she was Minister.

When I met her some years ago it was clear that she and her advisers spoke a form of Health creole. However then, speaking fluent Health was not as critical as it is today, especially in the misinterpretation of the meaning of vaccine percentages.

The Mystery of Jane Halton

Vaccine advances, including the remarkable success of mRNA technology, made it possible to develop jabs for a previously unknown pathogen in less than a year, rather than the decade or more it would traditionally take. But as much as we improved, the delivery of vaccines still took far too long. In the future, our goal must be to roll out vaccines in just 100 days. This goal, first articulated by CEPI, has been adopted and championed by the UK Government as part of its G7 Presidency. Achieving it could save millions of lives and trillions of dollars should we face another pandemic threat. – Richard Hatchett – June 2021

Richard Hatchett is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Oslo-based organisation formed in 2017. The following blurb, even suitably abridged, sets out the objectives:

Richard Hatchett is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Oslo-based organisation formed in 2017. The following blurb, even suitably abridged, sets out the objectives:

CEPI works to advance vaccines against emerging infectious diseases…and establishes investigational vaccine stockpiles.

CEPI also funds new and innovative platform technologies with the potential to accelerate the development and manufacture of vaccines.

CEPI is working with partners across the world on the development and manufacturing of a safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19 and is seeking US$2 billion from global donors to carry out this plan.

Australia has given CEPI a relatively small amount of $13million (half of which has already been provided) towards the $2billion. In addition to governments, notably the UK, the Gates and Wellcome Foundations have each given $100 million.

Richard Hatchett has had a remarkable career and it is outlined most relevantly in a recent book by the prolific Michael Lewis titled “The Premonition – A Pandemic Story”. In short, Lewis focuses on a group of scientists and doctors who spent years trying to ensure America was prepared for a deadly pandemic. A medically-trained epidemiologist, Hatchett is first mentioned in the book as having being recruited by one Rajeev Venkayya, a relatively junior medical graduate himself part of a group planning for governmental response to pandemics.

Serendipity is often but not invariably associated with momentous change. Dr Venkayya arrived at the Bush White House at a time when Bush, as described in the book, was “pissed”. Bush had been at the helm when 9/11 occurred; there had been the catastrophic Hurricane Katrina – and he did not know what to do. In fact, my personal memory from afar at the time of 9/11 was of the dazed, uncomprehending look on Bush’s face when he was interrupted reading a story to pre-schoolers, to be told of the planes crashing into the Twin Towers and the Pentagon.

Yet there, in this book “The Premonition”, it was said that in the summer of 2005, Bush read a book about the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak and the devastation wrought. The book influenced Bush to such an extent that he wanted a plan to prevent this happening again. Bush had had many plans pushed his way on a number of matters, a number of which yielded catastrophic situations occurring, for instance, in Afghanistan.

Yet this proved different.

At the time in 2005 we had the outbreak of avian flu H5N1, and dire predictions of massive loss of human life, which never eventuated. Yet in the previous two years, the world had got its first spread of the SARS coronavirus, the forerunner of the COVID-19 virus.

Bush listened to Dr Vekayya, who wrote down a sketchy plan – 12 pages “which amounted less to a plan than a plan to have a plan”. Bush asked Congress for $7.1 billion to spend on this three-part pandemic sketch plan, and Congress gave it to him. It was an insight into how Bush governed by instinct but, on this occasion, he was mostly right. Yet the business of getting a policy into place, which was little more than vaccinate and isolate, proved very difficult, given that it crossed the influential Centres for Disease Control (CDC) way of thinking.

To the Vekayya group another doctor was recruited, Carlton Mercer. He came from the Veterans Administration and over time this little-known figure became, with Hatchett, the vanguard for turning the Vekayya sketch into a defined course of action, namely when a pandemic appeared imminent, in the absence of a vaccine it was to go quickly and hard in locking down the community, close schools and social distance people from one other. The problem with people who genuinely drive change is that there is always the research/medical establishment prepared to cast aspersions. In this case, this was the CDC.

When Obama came to power, he stopped listening to these Bush appointees and their accumulated experience. He was bolstered in 2009 by predicted dire consequences of the swine flu pandemic – caused by another influenza virus H1N1 – that did not eventuate. Mexico had followed their guidelines; so what! America did not; and nothing much happened.

COVID-19 was yet to come.

Richard Hatchett in 2017 ended up running CEPI, which was a critical position as related in the book, because it was able to redirect substantial funding in the development of vaccines, particularly Moderna and AstroZeneca, when the pandemic struck and the Virus was isolated. Funding was also provided by CEPI to the University of Queensland for its ultimately failed vaccine. Considering the hype surrounding this group, perhaps more reliance was placed on its success than should have been. In any event, it left Australia with very few vaccine paddles, later in 2020. At that time Australia was basking in its success of suppression of the Virus.

Richard Hatchett in 2017 ended up running CEPI, which was a critical position as related in the book, because it was able to redirect substantial funding in the development of vaccines, particularly Moderna and AstroZeneca, when the pandemic struck and the Virus was isolated. Funding was also provided by CEPI to the University of Queensland for its ultimately failed vaccine. Considering the hype surrounding this group, perhaps more reliance was placed on its success than should have been. In any event, it left Australia with very few vaccine paddles, later in 2020. At that time Australia was basking in its success of suppression of the Virus.

Since leaving the advisory role to a President who had stopped listening to him, Richard Hatchett has been very active nevertheless.

The mystery of Jane Halton? Given her position as Chair of CEPI, which she is always flaunting, the question has been asked as to why she did not influence Australia in its acquisition of vaccines by Australia in 2020, given the directions being taken by CEPI, given the obvious international standing of the CEPI CEO, Richard Hatchett. I would have thought she would have told the Government what to do, as is her wont. She certainly should have known about the efficacy of the various vaccines under development around the world, including that of the University of Queensland, and the need to stockpile a range of vaccines, not just one.

Very strange, almost as mysterious as why she is the Chair of CEPI in the first place.

Sprod

A drawing of a Grecian urn. The athlete on the urn being offered a laurel wreath. The caption – “no thanks I’ll take the money.”

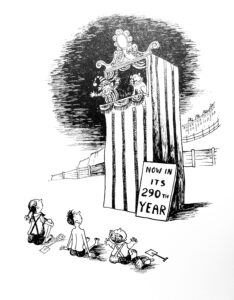

The children on the beach watching a Punch and Judy show. The sign against the beach stage read “Now in its 290th year”.

The children on the beach watching a Punch and Judy show. The sign against the beach stage read “Now in its 290th year”.

An exercise in whimsy.

George Napier Sprod was an Australian cartoonist who, for much of his working life after the Second World War, worked in England. A cartoonist who signed himself Sprod? Who would believe the name was not just a humorous pseudonym? But George Napier Sprod was indeed born in South Australia.

As has been written elsewhere, in 1938 at the age 19, George Sprod left home without notice. He had decided to ride his bike along the Murray River en route to Sydney. He got as far as Hay before selling his bike and continuing by train. Once in Sydney he set up residence in Kings Cross and started freelancing as a cartoonist and working as a street photographer.

World War II intervened. He joined up, became a gunner, was sent to Singapore, was captured and then was a POW in Changi until the end of the War. During that time he teamed up with Ronald Searle and the two of them edited a paper called “Exile”. It must have been difficult for the Japanese to comprehend, given their distinctive styles. Searle in fact had a marked effect on the Sprod development

After the War he went back to Australia, worked for a time on the Packer papers, the Daily Telegraph and Womans Weekly, found out he was not a political cartoonist and went to England, where he hit paydirt, particularly with then Punch Editor, Malcolm Muggeridge.

In the “Introduction” to a collection of Sprod cartoons, mostly ones that had appeared in Punch, published in 1956 under the title “Chips off a Shoulder”, Malcolm Muggeridge described Sprod’s drawings as very funny, with a gusto, an earthiness. “The inherent absurdity of human life positively pleases him, and his bold and uproarious situations convey this pleasure. I would say he was in no tradition at all, but just Sprod.”

Muggeridge, later on the Introduction, opined on why Australia produced and nurtured more humorous artists than anywhere else. He suggested it may have been the harshness of life and the vastness of Australia, which elicited the wry smile as the readiest and most natural response, as Muggeridge so elegantly puts it. Muggeridge mentions a number of Australian cartoonists, but lumped David Low in with them. Low, probably the most acclaimed political cartoonist of them, was a New Zealander, who did work for eight years in Sydney before spending the rest of this life cartooning in England.

Just before I left running the community health program in Victoria, one of my nursing team, as an impromptu gesture presented me with a first edition of “Chips off a Shoulder”. The year was 1979, the book having been published two decades before. On the fly leaf, she had written my initials and under these the words “A sense of humour” and then below at the foot of the page “Best wishes, always” followed by a long dash. I remember once she did ask what I would like as an epitaph. I don’t remember how this matter came up, but I remember my response, “I tried”.

It is funny what you treasure and would never sell. After I left the job, I never saw her again. Her name was Beryl.

But then I never went searching for Sprod, who by that time had retreated from England back to Australia because of some messy domestic relationship there. He died in Marrickville in 2003, I know that much and that he did go on to publish a number of other books of cartoons.

Where has All the Influenza Gone?

Influenza is very much part of the discussion swirling around the COVID-19 discussions. Reference is continually being made to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic; and reference is made to the fact that people have died of influenza in the past and we did not lock down Australia.

One can speculate about this. My view is that the Australian community has become used to the winter appearance of the virus, and there was always at the outset of “the flu season”, the Australian representative of the World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Reference on Influenza appearing to warn us of its dangers. Australia was thus well placed. Scientists at the Centre in Melbourne—one of six such centres globally—faced an imprecise predictive process because of the variability of the various strains. This explained the vaccine’s varying effectiveness year to year as the Commonwealth Serum Laboratory (CSL) tried to make the most effective vaccine to counter this shifty virus.

Thus, there is a yearly vaccine, and there were established rituals. Those working in the health sector were encouraged to be vaccinated, and each health centre, generally as part of infection control, provided a systematic approach. In any event the prevalence of influenza waned as the country emerged from winter.

People died, and in fact up to 2020, every year from 2014 onwards the number of people who died increased, almost reaching 1,000 a year – until 2020 when the number dropped to 36, and then this year nil. The average age of death was 88, and hence influenza mortality was conventionally believed to be confined to the very old.

This year the community was advised to space its influenza and COVID-19 injections. I had the influenza injection first, when it became available. This I did because early in the year the COVID-19 virus seemed suppressed and the Delta variant had yet to emerge as the scourge it has become. So, in my case, “vaccine hesitancy” was an artefact, because of the expert advice to space the injections.

There is much speculation about why this apparent extinction of influenza mortality has occurred. The first is that it is only a lull in the disease progression and it will come roaring back with enhanced infectivity. Others suggest that the measures taken in regard to the current pandemic, such as social distancing, better hygiene and school closures have contributed.

Whatever the core reason for the current situation of zero mortality, the course of the influenza virus should be closely monitored but, from this unexpected effect, it does suggest that the hard approach is working.

In 1918 the community was hit by the influenza pandemic which, some say, never really went away. It just became attenuated; but there have been pandemic years. I remember the Asian flu pandemic in 1957 because I ended up in Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. There have been outbreaks since, all caused by descendants of the Spanish flu virus, generally milder and seasonally self-limited. In summary, seasonal influenza has tended to kill the oldest and youngest in a society but has been less virulent since the 1918 pandemic – roughly half of those who died were men and women in their 20s and 30s, in the prime of their lives.

In 1918 the community was hit by the influenza pandemic which, some say, never really went away. It just became attenuated; but there have been pandemic years. I remember the Asian flu pandemic in 1957 because I ended up in Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. There have been outbreaks since, all caused by descendants of the Spanish flu virus, generally milder and seasonally self-limited. In summary, seasonal influenza has tended to kill the oldest and youngest in a society but has been less virulent since the 1918 pandemic – roughly half of those who died were men and women in their 20s and 30s, in the prime of their lives.

Why does the community not get so worried about influenza? First, I suggest it is because of its predictability. This is reflected clearly by the ritual of flu vaccine injections. Yet have the measure that have been put in place over the past two years fatally suppressed the flu virus? An open question.

Secondly, the coronavirus is different. The common cold is a coronavirus; the conventional wisdom – we don’t die of the common cold. But this is different, and the world was unprepared for this relative of such a mild disease to rear up and become a dangerous lethal virus, initially with no vaccine and then, as if in response to the emergence of vaccines, the more dangerous delta variant appeared.

Influenza has a predictability; this virus has not, especially as the messaging changes almost daily. These changes have increased the uncertainty, whereas the rules to deal with pandemics from a pure public health context have always been simple and unequivocal, with perhaps the added use of masks. Social distancing, school closure, restriction of all movement, personal hygiene, use of hand sanitiser, the importance of the reproduction factor – all well known.

Thirdly, another difference compared with influenza is the way this current pandemic has been handled in Australia. This is the politicisation with the inability of politicians not to interfere. The failure occurs when politicians panic, want instant solutions, unfortunately showing both ignorance and weakness at the same time. Politicians always seem to know better, especially when it interferes with business and political donors.

Ignore the public health rules, as is happening at present in NSW, and how long will it be before it is not only Afghani seeking refugee status in States with low rates of infection. One person, being a proponent of the “Let it rip” school of dealing with the Virus, said to me that he wanted to leave the country. Don’t worry. Currently, NSW is the place for you.

Mouse Whisper

Michael Kirby is an illustrious man of the people. He is known to deliver newspapers. Yet he has 30 honorary doctorates – quite a collection. There are 23 from Australian universities. Shame on the University of Western Australia and the University of Queensland. You are real laggards. But has anybody else got more honorary doctorates than our Michael K?

What a fancy dress party Michael, the Thespian, can stage. But why the number? I suppose it is because some people collect stamps; others, like Michael, collect Tudor caps.

My mausmeister has fond but distant memories of him and that other colourful figure of Sydney University politics, the late Vincent John Flynn. He remembers the things which were said about him by those two worthies during those halcyon days of student politics, not to his face, but after he had left a meeting early.

You see Flynn had inter alia currency issues; and so does Michael. Different form of currency; different definition. Both defined by spotlight, one avoidance of it, the other always searching for it.