There is one thing about the configuration of hotel/motel rooms. Much is made of the fact that “accessible” rooms are routinely part of a hotel’s room complement – but what does this really mean? When people think of disabled, they recognise that the signage for disability is the wheelchair. However, there is another level of disability which, on occasions, may require a wheelchair – it now tends to be described as “ambulant”, although that seems to only apply to bathroom doors. When I need a wheelchair, I use one that can be borrowed. This is sufficient. I can manage on two sticks, even with my balance problems.

But back to those accessible rooms. Bathroom/toilet facilities need to be user friendly. Wheelchair friendly facilities must have sufficient space and most disabled facilities recognise the need to eliminate steps. Nevertheless, many of these are not appropriately designed for the disabled who use sticks or crutches unless there are sufficient railings to assist navigating a wet floor, where sticks are liable to slip as one tries to walk on the cracks between the tiles to avoid sliding The criteria for accessible rooms definitely need to include non-slip-when-wet tiles.

What is also not factored in are the beds, which need to provide a safe place to site and reasonable ability to get out the bed. I use carer help, or else a chair located next to the bed to wrestle myself up. The mechanics are deceptively simple to assist sitting up and swinging legs over. The height of the bed should be related to the height of the person so ideally the height should be adjustable, particularly as modern beds seem designed for an accompanying ladder. The modern hospital may be the template. Hospital beds have a feature that makes them more appropriate, high-low functionality. The user can raise and lower the bed vertically, making a hospital bed ideal for people like myself, who need more assistance when getting in or out of bed.

The other issue is the inappropriateness of the chairs provided in most hotel/motel rooms – often rickety hard backed chairs or ludicrously low armchairs. Even rooms that purport to have a work desk rarely have a suitable chair on wheels. From my point of view, a decent office chair makes life much easier and I suspect for others, avoiding having to push a normal chair back and forth from a desk would be welcome.

The other issue is the inappropriateness of the chairs provided in most hotel/motel rooms – often rickety hard backed chairs or ludicrously low armchairs. Even rooms that purport to have a work desk rarely have a suitable chair on wheels. From my point of view, a decent office chair makes life much easier and I suspect for others, avoiding having to push a normal chair back and forth from a desk would be welcome.

It may be said that I am speaking from the viewpoint of a rara avis, but does anyone know? An ideal disabled room should incorporate some of the suggestions discussed above, and it would be useful to convene a working party to set the standard.

Considerations of Some Matters

Some years ago, we visited the first ghetto in the world which is located in Venice. When it was constructed to house the city’s Jews, the gates were locked at night, emphasising its quasi-prison conditions. The ghetto is far from the centre of Venice. Apart from a gaggle of Chinese tourists, the ghetto square was empty save for a Jewish family enjoying the balmy sunny day, sitting under a tree. The only jarring note was the bulletproof door to The Holocaust Museum. We did not go in. I had seen the gruesome museum in the old Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. One Holocaust Museum is enough. Pity, the Israeli government seems not to have seen it lately.

In any event we had eaten a delightful kosher lunch marred by the officious surliness of the staff. Quite obviously, non-Jews were not particularly welcome, even if we did have an inkling of the food taboos.

Reflecting on that I wonder when the world will be able to bask on the shores of the Gaza Riviera. Maybe without gates to lock the Israelis out.

The above were just a few introductory thoughts if you wish to read on.

Avraham Stern – who split from the Irgun to form the Lehi (also known as Stern Gang) in 1940 – had suggested securing support from the Third Reich.

Haaretz adds that Lehi representatives met with an official from the German Foreign Ministry in Beirut at the end of 1940.

“The establishment of the historical Jewish state on a totalitarian national basis, in an alliance relationship with the German Reich, is compatible with the preservation of German power,” the newspaper cites the Israeli document as saying. The Cradle, June 2023 (a journalist-driven American publication founded in 2021 covering “West Asia voices not heard in the world’s English-language media. That’s not the only differentiator. Not owned by any donors, and so they have no say over what is written or not.”)

Q: True or False?

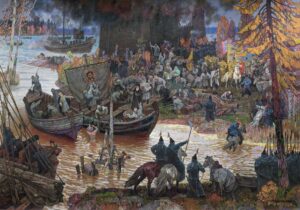

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw ghetto uprising began after German troops and police entered the ghetto to deport its surviving inhabitants. About 700 young Jewish fighters fought the heavily armed and well-trained Germans. The ghetto fighters were able to hold out for nearly a month, but on May 16, 1943, the revolt ended. The Germans had slowly crushed the resistance.

The SS and police captured approximately 42,000 Warsaw ghetto survivors during the uprising. They sent these people to forced labor camps and the Majdanek concentration camps. The SS and police sent another 7,000 people to the Treblinka killing center. At least 7,000 Jews died while fighting or in hiding in the ghetto. Only a few of the resistance fighters succeeded in escaping from the ghetto. – Holocaust Encyclopaedia.

Q: Tell me why the current Gaza situation is different from Warsaw?

The attendees hadn’t expected a policy shift from the meeting, according to the accounts, but felt confident that their concerns would be conveyed to Biden, to be taken into consideration in his public remarks about Palestinians. Two days later, the President made the comments questioning the accuracy of Palestinian casualties at a time when Arabic-language TV channels were showing nonstop footage of lifeless, dust-covered children being pulled from the rubble after Israeli strikes. –Washington Post

Could someone tell me why Israelis are viewed as more truthful than the Palestinians?

The Venetian Ghetto was the first ghetto instituted in 1516 by decree of the then Doge Leonardo Loredan and the Venetian Senate. It would be ironic if, by his actions in Gaza, Netanyahu emulates the Doge, albeit for a different reason, reviving the ghetto so that every Jew, whether Zionist or not, is worldwide forced to live in armed enclaves for their own protection.

When the Gunman Comes to Town

The following is from the Boston Globe response to an edited account of the mass shooting in Maine. I have spent some glorious times in Maine, although I have never been to Lewiston as far as I can remember.

The following is from the Boston Globe response to an edited account of the mass shooting in Maine. I have spent some glorious times in Maine, although I have never been to Lewiston as far as I can remember.

Mass shootings are a rarity in Australia although I well remember the Port Arthur massacre in 1996 when 35 people were killed. I was one of the few who saw the police film of the horrific aftermath, a coloured grainy film. It was a time when I had just stepped down as President of the Australasian Faculty of Public Medicine, and my successor strongly supported our Prime Minister’s response, which inter alia resulted in banning semi-automatic and pump action shotguns, without good reason. While there were concessions to the rural lobby, there were restrictions which, despite some high-profile shootings since, have seen deaths due to firearms decrease.

Nevertheless, what is interesting about this Boston Globe article is the description of the emergency medical response, given most of the shooting victims were dead. Those injured are not as newsworthy, given the concentration on the event and the number dead. How much of the response of Maine health professionals is applicable to the Australian situation?

Dr. Sheldon Stevenson was at home hosting 10 fellow emergency physicians when the call came in Wednesday night around 7:30. Colleagues at his hospital, Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston, were resuscitating a gunshot victim. More were on the way.

Stevenson, the hospital’s chief of emergency medicine, had been expecting this call to come one day; mass shootings had grown far too common.

With scarcely a word, the doctors stood up and decided who would stay behind and take over for the others the next morning. The rest sped the roughly 35 miles from his Portland home to the hospital.

Meanwhile, chief executive Steven G. Littleson and chief nursing officer Kris Chaisson had already fielded similar calls. There was an active shooter, and the local emergency dispatch center had activated “code triage,” alerting everyone at the medical center that a disaster was unfolding.

As the hospital braced for what would prove to be its worst disaster ever, the staff knew what they had to do, but knew little of what they might face. Ambulance crews were reporting possibly 15 to 20 victims from two shooting sites. But the gunman was at large, and there was talk of as many as five or six additional sites, possibly waves of patients streaming in all night.

Alerted by the code triage, doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, support personnel, about 20 to 30 people in all, assembled in the ER within minutes. As word spread throughout the medical community, the emergency room filled with 100 people ready to help. Blood supplies arrived from other hospitals. Five helicopters were parked outside, ready to transport victims across the region.

The first gunshot patient arrived at 7:24 p.m. Thirteen more would stream in over the next 45 minutes — many more severely injured patients than the hospital had ever seen at once.

By the time Chaisson, the nursing chief, got to the emergency department, four shooting victims were being assessed in the trauma bays and the ER was filled with “a sea of people.”

“It was an organized chaos,” she said. “There were so many people but they knew exactly what they needed to get done … It was like a work of magic.”

Littleson, the CEO role would coordinate everything that happened next. The hospital was full Wednesday night, its 170 beds occupied, and the emergency room was already busy with the usual crush of 25 to 30 sick patients, including some who were waiting for beds. The staff would have to somehow make room for an untold number of casualties. Patients were moved into holding areas and other available spaces.

“We knew that the patients coming out of the operating room would need critical care. We had to mobilize some of our less critical care patients to other floors, to free up the ICU to take care of these patients,” Chaisson said.

Nine gunshot victims went swiftly to operating rooms — their awful wounds an urgent and obvious diagnosis. Privacy rules prevent a discussion of individual injuries, but Dr. John Alexander, the chief medical officer, named the types of surgeons who worked on them to give an idea: four trauma surgeons, four orthopedic surgeons, a vascular surgeon, a cardiothoracic surgeon, and a urologist.

Stevenson, the emergency chief, said the hospital treats gunshot wounds at least every month. But typically they are from handguns and hunting rifles, involving a single bullet wound.

The wounds he saw this time were an order of magnitude more severe, because the automatic weapon the shooter used sprays people with multiple bullets and shrapnel that rips the flesh. “They’re devastating wounds. Lots of soft tissue injuries, vascular injuries,” he said.

Because patients had been rushed to the hospital, and then into surgery, some were still unidentified two hours later. “That was a very difficult time for the families and for us as well,” he said, but eventually family members were brought inside and the patients identified.

In all, 15 gunshot casualties were taken to hospitals: 14 to Central Maine, and one to St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center, also in Lewiston.

Central Maine discharged two less severely injured patients after treatment on Wednesday night. Another patient was transferred to Maine Medical Center in Portland because the Lewiston hospital didn’t have enough operating rooms. Two died in the emergency department, and one died after surgery at Central Maine.

On Thursday, one surgical patient was discharged to home and another was transferred to Massachusetts General Hospital because of the nature of his injuries. The patients cared for at St. Mary’s and Maine Medical Center were also discharged. Late Friday two more patients were discharged from Central Maine.

That means that, of the 12 injured survivors, five remained hospitalized on Saturday — four at Central Maine (three of them in critical condition) and one in stable condition at Mass General. Staff members had prepared for such an emergency many times, in drills and exercises. Just a month earlier, they’d done a tabletop simulation involving mass casualties.

“People have assigned roles,” said Alexander, who is an emergency physician. “They understood what their roles were. They stepped into those roles and they acted accordingly. They are just incredibly heroic.”

Once it became clear there were no more gunshot patients, the challenge was convincing day-shift nurses to go home, because they would be needed the next day. They took comfort huddling with their teams, and feared leaving the hospital.

“We had to almost push them: ‘You’re still safe. … Let’s get a security escort to your car and let’s try and get you home. You’re safe at home.’”

The next day the hospital was eerily quiet. With the shelter-in-place order in effect, the hospital cancelled surgeries and the emergency room saw just 35 patients all day, compared with 120 on a typical day. By Friday, as the hospital resumed normal operation, clinicians and workers who had been stunned and shocked started processing what had happened. Counsellors were made available throughout the hospital.

“Their training and their skills take over during the event. Emotions and feelings take over afterward,” Littleson said. “The grieving process will now unfold over the next couple of weeks. In some respects, the hard part has just begun.”

Littleson, who used to work at a hospital in New Jersey not far from Manhattan, recalls preparing to receive an influx of patients on 9/11. None arrived because there were so few survivors.

He thought of that when he realized that in Wednesday’s mass shooting, the 18 dead outnumbered the 12 injured survivors.

“The tragedy of this event,” Littleson said, “is that there weren’t more patients to care for.”

I think I know what he meant, but it could have been better said.

It’s Just Dust

“When you actually successfully regulate something, so that nobody sees it anymore, your very success is the thing that causes it to emerge again. Because it’s just lost in people’s minds.” Dr Frances Kinnear

Who remembers Bernie Banton? Do you remember David Martin? What did they have in common. They both died of asbestos-induced disease. One, Bernie Banton worked for the industry villain in asbestos – James Hardie – in the 1960s and 1970s.

The other was a naval officer who was Governor of NSW until a couple of days before his death from mesothelioma in 1990. He had been exposed to asbestos in the ships on which he served in his long career. The navy was his life, commencing as a midshipman and rising to the rank of rear admiral.

Asbestosis was a vertically integrated disease. By this I mean from the workers in the Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR) blue asbestos Wittenoom mine, which operated between 1943 and 1965. Here in the Hamersley Ranges, Lang Hancock started his career, in an environment where asbestos fibres are carried by wind and water everywhere, and disturbed by human activities such as walking or driving around the area. 7,000 workers and their wives and children succumbed.

This was the same story with asbestos with its cottonlike appearance, easily pulled apart or packed as insulation throughout buildings until 1984, when the dangers of the material became apparent, and the community gradually come to realise a deadly material lay in the walls of so many buildings built post-war. James Hardie was the major distributor where Banton and his two brothers worked for 20 years.

Then there were the people who worked in an asbestos-riddled environment, as the rear admiral did.

The problem is many employers, in response to public health problems, have sought to obfuscate, refuse to accept responsibility, lobby parliamentarians about loss of jobs and social catastrophe if the use of material is curtailed. Just muddy the waters, bugger the toxicity, until the community pressure through legal redress catches up with the employer’s venality. As was written a decade ago: “The banning of asbestos in 2003 was the culmination of a three-decades long process that got underway in the 1970s through the efforts of workers and their families, health professionals, and researchers” – note the absence of the employers, the big mining companies seemingly doing nothing to improve the situation.

The current furore about the silica-based material, which has become fashionable for kitchen countertops, but in the process of cutting the material to size, creates a silica-laden atmosphere. When I was entering my career as a doctor, silicosis was a major occupational health disease, contracted then by miners and quarry workers. It received so much attention and publicity as a cause of respiratory disease there was no controversy within the health profession as to this association. A major associated problem was that most of workers then were also cigarette smokers; the danger of cigarette smoking was comprehensively exposed by the work of Doll in the 1970s.

The current furore about the silica-based material, which has become fashionable for kitchen countertops, but in the process of cutting the material to size, creates a silica-laden atmosphere. When I was entering my career as a doctor, silicosis was a major occupational health disease, contracted then by miners and quarry workers. It received so much attention and publicity as a cause of respiratory disease there was no controversy within the health profession as to this association. A major associated problem was that most of workers then were also cigarette smokers; the danger of cigarette smoking was comprehensively exposed by the work of Doll in the 1970s.

In this current scenario, where the culprit is a fashionable kitchen countertop product that is silica held together by resin, one would think that it was a no brainer to ban the product.

As the SMH editorialised this week, The (Safe Work Australia) report (recommending a ban on this stone) was handed to the governments on August 16 but not released until last Friday. Despite the delay, the Minister for Workplace Relations Tony Burke then skirted the issue of a national blanket ban saying it was not reasonable to make a final decision without the public knowing the Safe Work Australian’s recommendations. Burke said a meeting of federal and state work, health and safety ministers would be convened by year’s end to consider the next step.

Mr Burke, who have you been talking to, when the dangers of silica are so well known even before you were a boy? Your response in the media is laughable. Why the delay? Who has been in your ear?

A Fashion Plate at the White House

At a dinner at the White House on Tuesday, Mr. Biden and first lady Jill Biden presented the Prime Minister with an antique writing desk, designed by an American company in Michigan, the White House said. The first lady gave (Jodie) Haydon a hand-crafted green enamel and diamond necklace.

At a dinner at the White House on Tuesday, Mr. Biden and first lady Jill Biden presented the Prime Minister with an antique writing desk, designed by an American company in Michigan, the White House said. The first lady gave (Jodie) Haydon a hand-crafted green enamel and diamond necklace.

The NYT covered the Albanese visit by sending its fashion editor.

In amongst all the plaudits, the visit fulfilled all the expectations outlined in my last blog. The Americans laid on the treacly flattery, and characteristically Albanese responded to his swain in the audience while talking at the dinner, by saying it will be all downhill from now on. He may be right, but not for the reason stated.

Biden treated Albanese as anybody would treat a fawning vassal. Let me indicate, as I have before, I am not a great fan of Biden, but watching him in government he gets it right most of the time. Hooded eyes, which mean it is difficult to assess his mood, a flawed man who has spent most of his life in Washington, a man who has grieved far more than most of us, Biden has a residual advantage – that “Pepsodent” smile. I would imagine that if I were in the Albanese shoes, how seductive that would be, especially if I needed a father figure.

The treatment: “Don’t be a naughty boy and play with that kid across the road without telling us. Otherwise, I’ll send you to bed without your banquet.”

Thus, Albanese is lucky – slap on the back, not on the wrist – yet. Depends now on how he navigates China. The removal of tariffs is probably more important than some hypothecated underwater war toy (if ever launched at a time when “AUKUS” has replaced “obsolete” in the Australian vocabulary.)

Albanese is lucky. I surmise this US administration cannot countenance Dutton, especially following the Morrison debacle. However, Trump would be another matter. Yes, it is Halloween this week.

Mouse Whisper

Ever heard about my Andean cousin, the leaf eared mouse. They have been called “extremophiles” Why? Well let the current issue of Science set the scene:

Few places are as inhospitable as the top of Llullaillaco, a 6700-meter volcano on the border between Chile and Argentina.Winds howl nonstop and no plants live there; daytime temperatures never get above freezing and plummet even more come nightfall. Oxygen levels are just 40% of those at sea level, too low for mammals to live there —or so biologists thought until 3 years ago when a research team captured a live leaf-eared mouse at its summit.

That has proved not to be a fluke as climbers in the high Andes have seen the mouse scurrying across the snow searching for lichens to feed upon.

There you are! Mice on top of the world.

Our kitchen benchtop is Corian, a synthetic material composed of acrylic polymers and an aluminon trihydrate extracted from bauxite. Marble too has negligible silica, but natural granite and its synthetic offshoot Caesarstone has a variable amount up to 90 per cent silica. Corian is cheaper, but not so resistant to stains and chipping apparently as Caesarstone.

Our kitchen benchtop is Corian, a synthetic material composed of acrylic polymers and an aluminon trihydrate extracted from bauxite. Marble too has negligible silica, but natural granite and its synthetic offshoot Caesarstone has a variable amount up to 90 per cent silica. Corian is cheaper, but not so resistant to stains and chipping apparently as Caesarstone.

After the First World War a Scot called McLean Kay set up a tea plantation of nearly 900 hectares in Southern Malawi. This estate is called Satemwa, in the centre of which is Huntington House, the residence of the Kays. We spend a couple of nights there. It is not the main tea picking season, but we pass a line of men plucking tea leaves and placing them in shoulder baskets. Here both men and women share the load, unlike earlier in the year, where I had seen in Sri Lanka near Kandy tea leaf being picked by women with their baskets supported by a headband around their foreheads. Here the baskets were supported by the shoulders and the Malawi terraces were not the precipices of the Sri Lanka tea plantations where goats, let alone women with heavy baskets, would be hard pressed to cling. Malawi was way more considerate in the way the tea had been planted for the workers.

After the First World War a Scot called McLean Kay set up a tea plantation of nearly 900 hectares in Southern Malawi. This estate is called Satemwa, in the centre of which is Huntington House, the residence of the Kays. We spend a couple of nights there. It is not the main tea picking season, but we pass a line of men plucking tea leaves and placing them in shoulder baskets. Here both men and women share the load, unlike earlier in the year, where I had seen in Sri Lanka near Kandy tea leaf being picked by women with their baskets supported by a headband around their foreheads. Here the baskets were supported by the shoulders and the Malawi terraces were not the precipices of the Sri Lanka tea plantations where goats, let alone women with heavy baskets, would be hard pressed to cling. Malawi was way more considerate in the way the tea had been planted for the workers.

History does not celebrate the first skin-eaters, cultures around the world now enjoy skin recipes — whether Canadian scrunchions (pork rind), Indonesian krupuk kulit (beef skin), Jewish gribenes (chicken or goose skin cracklings with fried onions), Mexican cueritos (pork rind), Slavic cvarci (pork crackling) or Vietnamese tóp mo (fried pork fat).

History does not celebrate the first skin-eaters, cultures around the world now enjoy skin recipes — whether Canadian scrunchions (pork rind), Indonesian krupuk kulit (beef skin), Jewish gribenes (chicken or goose skin cracklings with fried onions), Mexican cueritos (pork rind), Slavic cvarci (pork crackling) or Vietnamese tóp mo (fried pork fat).