Arachibutyrophobia is the fear of peanut butter sticking to the roof of your mouth.

Kingaroy is the peanut growing centre of Australia. The terracotta soil is apparently excellent for the cultivation of the underground peanut, and my wife in a spirit of horticultural patriotism only buys Kingaroy peanuts.

Kingaroy is the peanut growing centre of Australia. The terracotta soil is apparently excellent for the cultivation of the underground peanut, and my wife in a spirit of horticultural patriotism only buys Kingaroy peanuts.

Now Kingaroy is in Queensland and is famous for being the home for Joh Bjelke Petersen, part of a Danish Lutheran family. His grandfather, Georg and grandmother, Caroline, migrated from Southern Jutland initially to Hobart. One of their children, was Carl Georg, who became a Lutheran pastor, married Maren, another Danish immigrant, and departed to New Zealand. Joh was born here in Dannevirke in 1911.

This township was founded by Norwegian and Danish immigrants, who were brought to New Zealand by the government in 1872 to cut down the forest which covered much of southern Hawke’s Bay and then to farm the cleared land.

Carl was sickly and the family migrated back to Australia and settled in Kingaroy, established a farm and the association between Joh and the Peanut was born. One of the many Joh quirks was that he spoke Danish fluently, but when he eventually went back to Denmark, his heavily guttural rural dialect made him very difficult even for the Danes to understand. They were not the only ones, especially when he reverted to English.

I only met Joh once when, of all people, John Button, the puckish Labor senator introduced me at a reception in King’s Hall. What struck me was how dead his eyes were. Even people with the perceived deadest of eyes like Greg Norman could not compete with Joh’s level of deadness.

I have worked around Queensland, and for a period a close friend of mine worked in Kingaroy and invited us to visit.

The legacy of that visit long term was the purchase of a collared T-shirt which had been deliberately “dyed” with the soil. Over the years, the colour has faded, but I have never had to use the sachet of Kingaroy soil which came with it, to “re-dye” it. I heard that the wives of the peanut farmers always claimed that their husbands brought the soil to bed, and for those who did not wear pyjamas, it was red sheets in the sunrise.

One of the bonuses of Kingaroy is that the Bunya Mountains are close by. These Mountains are an isolated segment of the Great Dividing Range. When you drive into these mountains as we did, we entered a brooding, mist enshrouded forest area, which remains subtropical yet cooler due the thickness of the forest cover and the fact that the roads climb to nearly 1,000 metres.

Bunya pines are a member of the Araucaria family. They used to be much more widespread than they are now. One of the few remaining areas is the Bunya Mountains, the remains of an extinct volcano, ostensibly 30 million years old, where the Bunyas grow well in moist basalt soil.

Bunya Pines grow up to 50m tall, and in summer are potentially dangerous, because they have this unpredictable knack of ‘bombing’ with their nut. These nuts can weigh up to 10 kgs, so being hit with one of these is potentially lethal if one is unfortunate enough to be standing under that Bunya. Despite the dire warning, it is difficult to find any record of a person who has actually died by Bunya cone.

Bunya Pines grow up to 50m tall, and in summer are potentially dangerous, because they have this unpredictable knack of ‘bombing’ with their nut. These nuts can weigh up to 10 kgs, so being hit with one of these is potentially lethal if one is unfortunate enough to be standing under that Bunya. Despite the dire warning, it is difficult to find any record of a person who has actually died by Bunya cone.

While we were in the Mountains, we bought five Bunya saplings. Why? When I thought about it later, I rationalised that we would nurture them and then give them away. The concept of growing five trees with the potential to grow to fifty metres in a suburban garden was more than daunting – it verged on madness. It reminded me of the story I once heard, perhaps apocryphal, of some deranged inner suburban arborist, who planted twenty-four lemon gums in a postage stamp courtyard. As a result, so much water was sucked up by the eucalypts, that all the walls of the houses lining the square were cracked.

Thus, we did not plant any of them in the garden, kept them in pots. As they grew larger and larger we offered one to our gardener, who gave it a more suitable home on his country property. We also gave one each to the sons, and kept two. One is stacked in a small pot, like a Chinese woman strapped in tiny shoes, yet has continued to grow against all the odds. We put it out in the lane, on the grounds that it would be taken and given a better home than the one we could give it. It is still there defiantly growing. Its sibling is growing slowly but robustly in the garden, still in a pot.

Time to go back into the land of the Bunya. The nuts are edible, and I once picked up a cone in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens, and the cone began to unravel into a strings of these nuts. I threw the nuts away. It was the Age of Bush Tucker ignorance.

Lobster – I have Tasted Everywhere, Man!

I have had many wonderful meals of lobster, which have been taken from the sea where they live a salty existence. I write that to distinguish them from crayfish, which are freshwater.

The few times I cooked lobsters, I gave them a merciful death by drowning them in freshwater. Takes time, but I feel more at ease than the horrendous practice of throwing them into boiling water or shoving a long knife up their spine.

One of the privileges of being an Australian is the number of places around the continent where lobster is available – as a rule of thumb, lobster is available in any month which contains the letter “r”.

There are two types of Australian lobsters, the western rock lobster and the more widespread southern rock lobster. The place where we have gorged on western lobster was on the Abrolhos, the long coral reef, which lies off the Western Australia coast.

These lobsters undergo a synchronised moult in late spring, when they change their normal red shell colour to a creamy-white or pale pink. The lobsters are then known as ‘whites’, until they return to their normal red colour at the next moult a few months later. The lobsters harvested in the ocean near the Abrolhos tend to be smaller, but a fresh lobster is a fresh lobster.

The southern rock lobsters leave their signature along the Limestone Coast of South Australia, and we once ate a lobster purchased from a seafood factory, beautifully cooked. We went down to the foreshore with the lobster and chips. There is something about eating seafood overlooking the Southern Ocean, especially if you love sea gulls.

Then, the next lobster port of call is the Victorian township of Port Fairy, where we once had a country cottage. Before the days of tagging, one could go down to the fishing boat and buy a lobster directly off the boat.

Finally, there is Tasmania where, from the early days of travelling there, lobster was always available. There was a woman who even grew them in tanks. On one occasion she provided one for us free. For a time, as with Port Fairy, you could go down to the Strahan harbourside where lobster was readily available from a shop on the quay.

Then there were none. Why? Most of the catch was exported to China or ended up in high-priced local restaurants around Australia. When China banned the import of Australian lobster, for a brief period there was a glut.

Just after alighting from the plane in Hobart, one had barely left the airport before being enticed by signs on the caravan of “freshly cooked” lobster. On that visit, lobster availability was more evident than even in the days when lobsters were not tagged.

Needless to say, the underground lobster trail to Asia has re-started with intermediate stages before the ultimate Chinese destination being in places such as Singapore to conceal the Australian nature of this cretaceous contraband. As a result, the price of lobster has risen as the local supply dwindles.

But in the meantime, I have developed an allergy to lobster.

Bisque Funder

John Funder is a remarkable polymath in his own write. He and I met in first year medicine, both children swaddled in the cloth of private male schooling, both sons of doctors. He was a Xavier lad; I wasn’t. Xavier taught ancient Greek; he was well steeped in the classical; he was a glittering research scientist. As for myself, I did Latin reasonably up to year 12 and obtained a mediocre PhD in researching angiotensin I & II.

Funder was and will always be my cynosure of “perceived relevance”. Whenever he came into my life, I always knew I was going through a phase of “faux-influential” – somebody worthy of being recognised, if not courted. One of those times occurred in 1973, when he was working in Hamburger’s Laboratory in Paris. No, this was not the scientific arm of McDonalds nor was it the crucible of “French fries” science.

Jean Hamburger (OM-boo-yeh) in fact was no joke. He was an eminent renal immunologist, whose pioneering work facilitated renal transplantation; and he even coined the word “nephrology” to describe the discipline of renal medicine and naturally was père de la néphrologie.

Funder, as was his wont, was thus living in Paris. It was early summer and as part of his overseas trip, Snedden had included Paris in his itinerary. The Department had booked him into the Hotel Georges V on the Champs Elysees. The suite which was allocated to Snedden was modestly luxurious and overlooked the Champs Elysees rather than the antique plumbing, which was my view from one of the rooms at the back, presumably once part of the servants’ quarters. I always remembered how spare it was, considering what it must have cost the Australian Government.

One evening, Snedden went off on a prior engagement with one of his banker mates, and I was left to my own devices for dinner. The telephone rang. It was Funder, who had tracked me down to the Hotel. As I was about to dine on my own, I invited him over to join me for dinner.

Funder took over the menu. His intention was that the meal would do justice to the fact that he was in the Georges V, a scientist on a meagre salary who deserved the best the Georges V could provide. I was not particularly well, and a week later I was seeing a Harley Street specialist, who drained my ear of pus.

But what I remember was Funder introducing me to lobster bisque. The bisque was luxuriant and there seemed to be litres of it. But I excused myself early; Funder delicately left me with the bill. I have had bisque since, but never in Paris on the Champs Elysees – nor with John Funder.

The Book Lender

My love of books had started as my father gradually built up his collection of Penguin books. I never asked him what fascinated him about these books, but as he collected them, from an early age I was surrounded by these colourful paperbacks, beginning with the children’s series called Puffin. There were even Baby Puffin books, but I bypassed this first step on the literature ladder.

Allen Lane, the founder of these paperbacks, had always said that the Penguin book was there to entertain and the subsequent Pelican line to instruct. Lane labelled his various types of books after birds beginning with “P”. Why? Well, he took the bird idea from a line of German books published by one Albatross Press.

My wife suggested that this segment of my life be recorded for posterity. I was in a junior school and it was just after World War II, and the library in the school was full of those daring-do books which seemed to be reminiscences of men who had fought in the Boer War or were generally putting “those native chaps” back in their place. These books were daunting to pick up let alone read, encased as they were in extravagant hard covers.

My mother banned me from having comics, although I remember a period where I managed to obtain Bosun & Choclit, which provided a diet of both ageism and racism in a jocular form, an ideal socialising force for us bambini, I don’t think.

I remember buying my first Champion, an English “boy story paper” at the newsagency at Flinders Street station, and my mother relented. Then for some years I regaled myself with stories about Rockfist Rogan, a World War II air ace, Colwyn Dane, a “tec”, Danny of the Dazzlers, a football team which seemed to be modelled on Arsenal, with feeder teams such as the Glimmers to construct a hierarchy of teams based on luminosity. There was the obligatory school hero, Ginger Nutt, “the boy who took the Biscuit”.

I remember buying my first Champion, an English “boy story paper” at the newsagency at Flinders Street station, and my mother relented. Then for some years I regaled myself with stories about Rockfist Rogan, a World War II air ace, Colwyn Dane, a “tec”, Danny of the Dazzlers, a football team which seemed to be modelled on Arsenal, with feeder teams such as the Glimmers to construct a hierarchy of teams based on luminosity. There was the obligatory school hero, Ginger Nutt, “the boy who took the Biscuit”.

I became steeped in Pommy argot, learning for instance that dribbling was not necessarily of sialic origin. These stories shielded one from reality; a shadow may pass across the storyline but always the stories ended in the sunlight. Life was a jolly jape, where success came to the eponymous heroes.

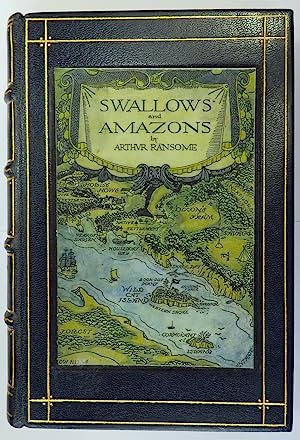

There were two streams of books that were popular. One was the Biggles books, with his sidekicks, Algy, Worrall and Gimlet. The others were the Swallows and Amazons series of Arthur Ransome, children’s adventures mainly on Cumbria lakes and the Norfolk Broads.

There were two streams of books that were popular. One was the Biggles books, with his sidekicks, Algy, Worrall and Gimlet. The others were the Swallows and Amazons series of Arthur Ransome, children’s adventures mainly on Cumbria lakes and the Norfolk Broads.

I am not sure how it started but somebody asked me for the book I was reading, and I lent it him. It was the last I saw of the book. But then I had many books, which included some that had been written with children about 8 or 9 years old in mind. I decided to set up my own lending library, and soon I was doing a roaring trade in lending my books out at threepence, tuppence or a penny. I might have asked for sixpence for the better book. I recorded each transaction in a notebook, and my classmates were remarkably honest in returning the books.

But such an enterprise only had a limited life expectancy. One day, when I was finalising a transaction on the stairs, the principal walked by and asked me what I was doing. I told him. Then he asked me to come to his office.

At a school where the sons of successful business persons roamed, I was forbidden to carry out any more trade. It was just not the done thing, you know, to earn money by exploiting my fellow classmates. He was very nice about it, but he could not have his pupils participate in trade. Heaven could wait!

In the meantime, I have accumulated books my whole life, without ever setting up a bookshop.

Haven’t I Seen You before?

Genetics put them together, and epigenetics and microbiome pulls them apart. – Dr Esteller

According to one study, the likelihood of two people sharing the exact facial features is less than 1 in 1 trillion. Put another way, there is only a one in 135 chance that a single pair of doppelgängers exists on our planet of more than 7 billion people. Yet another source says that there are six people in the world, who can be mistaken for you, excluding twins and triplets.

One Canadian photographer, François Brunelle, who happened to be a doppelgänger for Rowan Atkinson was intrigued with this whole area. He photographed an extensive portfolio of doppelgängers. Looking through his photographs, they are stunning even given that being a photographer, he would have photographed the pairs in the most favourable light.

Last year, Dr. Esteller, a Spanish scientist reported on research where he recruited 32 pairs of lookalikes from Mr. Brunelle’s photographs to take DNA tests and complete questionnaires about their lifestyles. The researchers used facial recognition software to quantify the similarities between the participants’ faces. Sixteen of those 32 pairs achieved similar overall scores to identical twins analysed by the same software. The researchers then compared the DNA of these 16 pairs of doppelgängers to see if their DNA was as similar as their faces.

Dr Esteller found that the 16 pairs who were “true” doppelgängers, sharing significantly more of their genes than the other 16 pairs that the software deemed less similar. It all came down to the more they were alike, the more they share important parts of the genome.

However, DNA alone doesn’t tell the whole story of our makeup. The epigenome, the lived experiences, and those of our ancestors, influence which of our genes are switched on or off. Then there is one’s microbiome, the microscopic accompaniment made up mostly of bacteria and viruses, which is further influenced by our environment. Thus, while the doppelgängers’ genomes were similar, their epigenomes and microbiomes were different – working in the opposite direction to the genome.

Alfred Hitchcock’s film, Vertigo, released when I was a late teenager, impressed me by the element of shock, where the one character portrayed by Kim Novak is the lookalike of herself, and where she is forced to re-enact events which had gone before – and emphasises that when the concept is artificially fused, there is a certain madness. Jimmy Stewart does madness very well as he seeks to break the fusion apart.

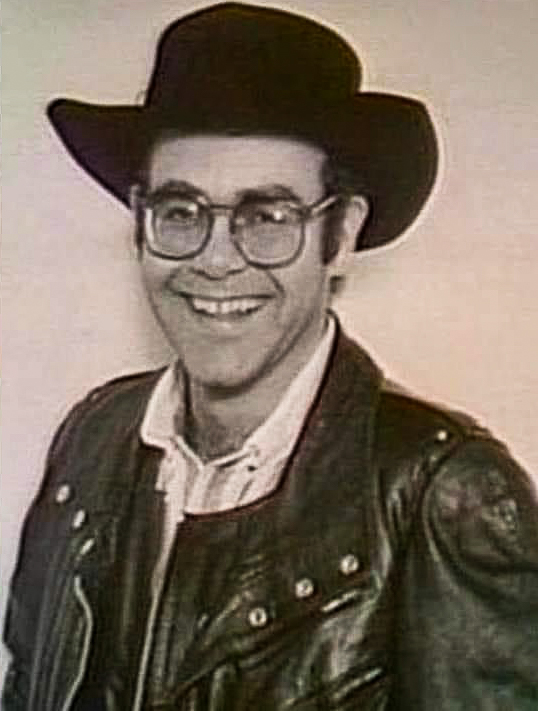

Thus, this area has always fascinated me – the more so when I was said to resemble Elton John. I remember a time when Elton John was touring Australia and sustained a leg injury which put him in a wheelchair. One of my associates at the time said: “Put Jack in a wheelchair with a cowboy hat and nightclubs, here we come!”

Thus, this area has always fascinated me – the more so when I was said to resemble Elton John. I remember a time when Elton John was touring Australia and sustained a leg injury which put him in a wheelchair. One of my associates at the time said: “Put Jack in a wheelchair with a cowboy hat and nightclubs, here we come!”

It was the time when Elton was about to marry a woman, but even so I suspect it would have been quite a ride, if we had gone through with the wheelchair tour through a confused world of gender identity.

The first time I realised that he was my look-alike was back in 1972 when two young women at a work barbecue started looking at me and then began whispering and giggling. At that stage, I had never heard of Elton John. But somebody showed me a record cover, and the similarity was immediately recognisable. When you are both mesomorph with heavy legs, wear glasses and have at certain angles, a similarity in features, then does that make one a lookalike – a sosie – a doppelgänger – a double? It may.

With me, it has never been more than a quirk, occasionally a conversation piece – but the confounding variable is lifestyle and, with time, nobody could be a genuine doppelgänger for such a unique personality as John – certainly not a retired guy called Jack without the same array of wigs. I really conform to the research findings about environmental push-back.

Mouse Whisper

There were two celebrities who looked alike. In a restaurant, one approached his doppelgänger, and before he could say anything, the first looked him up and down slowly, and said “My, you are a handsome fellow!” and without further ado got up and left.