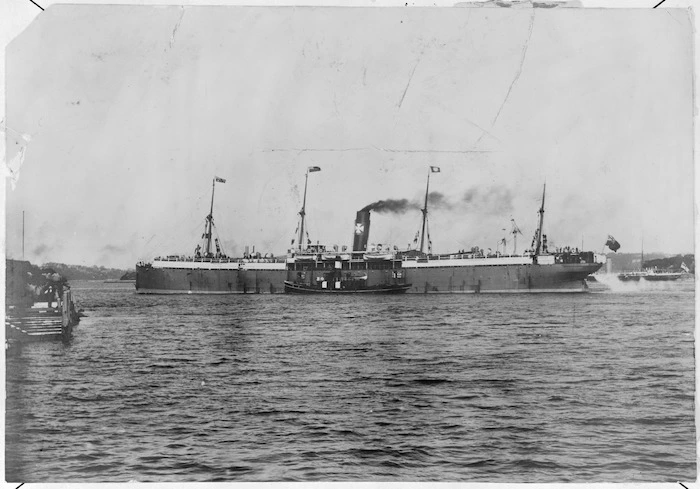

The first Royal Commission commenced in August 1902 and ended two months later in October 1902. The Royal Commission was established to inquire into and report upon the arrangements made for the transport of troops returning from service in South Africa on the S.S. “Drayton Grange”.

The Drayton Grange, a 6600-tonner, was a troopship chartered to return Australian soldiers from the Boer War in South Africa. With more than 2000 aboard, the ship was overcrowded and unsanitary, with inadequate medical facilities.

By the time the ship docked in Melbourne on August 7, 1902 at the end of a month-long voyage, five were dead and another 12 died subsequently.

From the ship docking in Melbourne to enactment of the Act, to appointment of Chair, to handing down the results of the Royal Commission took two months.

There were no specific recommendations. But this paragraph apportions a level of blame, “We find that the responsibility for what, under the circumstances of the troops and the nature of the voyage, was undue crowding of the vessel, for the insufficiency of hospital accommodation, and for the defects in the deck sheathing, rests with the Imperial Embarkation authorities in South Africa; for the non-landing of the sick with the authorities in West Australia; and for the failure to improve, and the unnecessary aggravation of, the undesirable conditions in the vessel, on the Officer Commanding Troops and the Medical Officer in Charge.”

Royal Commissions take a considerable time. Perhaps Mr Justice Toose, who undertook an investigation into veteran affairs in the 70s, set the exemplar for the timeless Commission. He asked for several extensions, and there was often a tone in ridicule about this Inquiry which extended for five years for 800 pages and 300 recommendations.

Toose’s exercise has been dwarfed by $600m spent on the Disability Royal Commission; the Government’s response is not to implement the 222 recommendations in its 6845 pages, but to set up a Taskforce of bureaucrats to respond, thus delaying any implementation by at least 18 months.

Why the length? To justify the Royal Commission, which remains divided in its recommendations and service. Think about the time and cost for a split decision.

Given it was headed by a former Federal judge, Ron Sackville, once described as a law reformer, his Commission’s major recommendations just tread the familiar line of a new Act, a Disability Commission, and a complaints mechanism. Big deal; could have taken a good dinner to come up with these recommendations.

Recently, at the Australian Legal Information Institute (AustLII), the Attorney-General, Minister Dreyfus, made a lukewarm comment ending in a crafted ambiguous conclusion, where “clarity” would not be the word I would use.

“None of this is to say that royal commissions should necessarily be a government’s ‘go to’ option when a difficult issue arises. Most areas of public policy are best dealt with by the ordinary work of policy development by Ministers and their Departments, and even when an inquiry is merited, a royal commission might not be the most appropriate kind. Very often, matters concerning the operation of government will be best dealt with by an ordinary administrative inquiry.

Nonetheless, it is certainly clear why royal commissions have occupied such a significant role in our system of government over such a long period.”

Dreyfus had recounted, prior to this excerpt, that Royal Commissions had advantages. These were independence, information gathering, and to hear vox populi. All are relative. How independent can it be when the government selects the commissioners; information gathering can be subjective, as can listening to the people, although this takes a bleak view of government. But why not? This current government, increasingly prone to secrecy, does not make me more supportive of royal commissions, expensive exercises in marching on the spot.

The major problem with Royal Commissions is that they raise expectations. The government looks for the recommendations with which it broadly agrees, and often these are the most trite.

To me, a useful Royal Commission should make recommendations, which are not “feel-good” waffle, but should isolate the changes which could be made, theoretically from the next day. Key recommendations must be coherent and limited in number. It helps if one happens to be reductionist in approach. It provides that clarity which Dreyfus advocates.

Fashionista

“Brunel, along with numerous young models, was a frequent passenger on Epstein’s private jet, according to flight manifests. The agency owner also allegedly received $1 million from Epstein in 2005, when he founded MC2 with his partner, Jeffrey Fuller; although Fuller and Brunel denied any such payment from the billionaire pervert in 2007, when rumours started swirling, Sarnoff got confirmation from a former bookkeeper at the agency. Whether the money was a secret investment in MC2, or a payment for Brunel’s services as a procurer, is unknown. Brunel also visited Epstein in jail.”

Now there is one industry that needs to be examined – the fashion industry. Not only does it create a great amount of detritus, but the question is how many occupational health and safety rules does it violate?

For instance, a modelling career for women starts between 14 and 16 years and is over by the mid 20s. It is an industry which cultivates the “stick insect” look and emphasise that ugliness by forcing the models in very high heels to traverse the catwalk in that uncomfortable stalk, which seems to be de rigeur.

For instance, a modelling career for women starts between 14 and 16 years and is over by the mid 20s. It is an industry which cultivates the “stick insect” look and emphasise that ugliness by forcing the models in very high heels to traverse the catwalk in that uncomfortable stalk, which seems to be de rigeur.

For example, in one instance more than half the models in a US survey found were told they wouldn’t be able to find any more jobs if they didn’t lose weight. So, not only are models being pressured to lose weight, but they’re being told that their livelihood depended on it. As the writer said, “this immense pressure to lose weight in order to protect your ability to make a living is unacceptable. It’s incredibly damaging to models’ mental health and their overall safety and wellbeing.”

Health professionals are always concerned with anorexia and bulimia as well as body dysmorphia in young females. Once you step into the malnutrition zone, then there are consequences, not the least of which is osteoporosis. The overlay of mental health in these women, especially when they are discarded for a younger wave of aspirants, undoubtedly leaves a legacy.

The 2017 movie “Straight/Curve: Redefining Body Image” was made by an Irish born US film maker Jenny McQuaile. It reveals how beautiful pictures in magazines or TV shows in the fashion industry have actually affected the current generation of women and young girls.

In a comment on the film: it linked the exposure of images of underweight air-brushed female bodies to unhealthy eating habits and decreased self-esteem, so poor body image can lead to even more serious consequences. Overweight status, self-perception found that girls who were unhappy with their appearance were at a significantly higher risk for suicide. The evidence is overwhelming.

Against this, there is the further depressing statistic that Australia is the second largest per capita consumer of textiles in the world, after the USA. Indeed, the average Australian consumes 27 kg of new clothing a year.

Revenue from the Australian apparel market is expected to reach $20 billion before growing by slightly more than two per cent per year until 2027. The industry contributes 1.5 per cent to the Australian GDP, generates $7.2 billion in exports each year, and employs more than 489,000 people – 77 per cent of whom are women. There lies the kernel for the case for government not interfering in the catwalk disease. It creates income.

The other resistance would come from the “social X-rays” that form the catwalk audience. It beats me how one could not be repulsed by seeing these emaciated nymphets in the flesh, unadorned by the photographer’s illusionary tricks to emulate images of unattainable perfection; instead, they look as if they have been released from a concentration camp decked out in grease paint.

The racing industry relies on dieting in jockeys trying to keep weight down to 54kg, above which life for most jockeys’ rides is limited unless they are in the top echelon or are a jumping jockey, and in this later instance their races are confined to Victoria and South Australia.

The racing industry relies on dieting in jockeys trying to keep weight down to 54kg, above which life for most jockeys’ rides is limited unless they are in the top echelon or are a jumping jockey, and in this later instance their races are confined to Victoria and South Australia.

You just must see such jockeys in their forties with their sunken cheekbones and hollow eye sockets – excessively thin and also liable to osteoporosis. Unless you are dwarf, this prospect awaits. Some of the jockeys on the tiny side have an extraordinary physique with disproportionate limbs, but it is a more dangerous occupation – falling off a horse at full gallop in the middle of a race is more so than marching down a catwalk.

A study in Victoria in which jockeys completed an anonymous questionnaire, resulted in 75 per cent reporting routinely skipping meals and 81 per cent restricted food intake in the 24 hours prior to racing. Sauna-induced sweating was used by 29 per cent of respondents and diuretics by 22 per cent to aid in weight loss prior to racing. Smoking is less prevalent and induced vomiting and the use of laxatives are more in the realm of the fashion industry – not to mention use of the peacock feather.

At least, the racing industry has made token recognition of the problem with raising the minimum weights in most races. There are well-placed photographs of the champion jockeys with judicious use of healthy diets and strenuous exercise. But then, have they metaphorically been air-brushed?

Hence the need to evaluate whether Society is aiding and abetting an unhealthy lifestyle, which nevertheless suits a cohort of influential people. Moreover of course, there is the view that an individual has the freedom to do what they wish; but does a fourteen year old have that unfettered right to condemn herself into a life of starvation and slavery? I think not.

In a Brown Study

Millennials come in for scorn from the dealers I meet. Millennials don’t want things; they want “experiences,” according to opinion surveys. Many dealers are befuddled by this attitude as well as by millennials’ texting and tweeting. Antiques are not easily translated to the digital realm. They’re not part of the point-and-click universe. They’re not Instagrammable. Look at us on this brown couch! And look at this thumbtack Windsor chair from 1825 in faded yellow paint. It has such a rich “patina,” the touch of history. Nope. That’s just a worn-out old chair. – New England magazine

I remembered one of my contemporaries was besotted with brown furniture. He lived in one of those large Victorian mansions with high ceilings, poor lighting and faded wallpaper. The fittings, the staircase all brown – and moreover the furniture was brown – different shades of brown, but nevertheless very brown. If it was not mahogany, it was French polished or varnished, all to a high-quality brown.

Mahogany is exotic – Cuban or Honduran was always part of the description. There is an Australia hardwood eucalypt, which is called among other names, Australian mahogany. Another major contributor to this brown diaspora was the native cedar, logged from Queensland forests. I have a red cedar desk which my great-uncle owned and used daily in his work as a well-known early Melbourne architect. There was a what-not which he purchased, always mentioned to me as Chippendale. It was not.

Thus, I had inherited from both my maternal and paternal lines a considerable amount of brown furniture, to which I added further items when we moved into our terrace house in Balmain in 1987. Then it was not cheap, and in fact the bookcase was very expensive, being beautifully made with inlaid decoration.

In one of our storerooms sits a round walnut table, used for many years for dining. Walnut is brown enough to be unwanted, as this is.

But that was another era. Now brown furniture is shunned. The current open space house with few interior walls encourages a light and airy existence with clean cut steel and corian kitchens. Then there are glitzy bathrooms where the standalone brilliantly white bathtub made of fibreglass and stainless steel reinforced with polyester resin, stands in the a room bordered by wash basin, shower recess and toilet. Here, use of brown tiles would be somewhat confusing.

And after all, who has a brown car in their double garage after you walk through the laundry where, if you are hunting for brown artifacts from a lost Brown Age, it is there you may find such relics. But probably not. Even the cleaning equipment is variegated in colour- and “whitegoods” are just that, unless the essential utilities are now with facades of blue-grey steel -be it a washing machine or refrigerator.

Now left on the footpath, sideboards, chiffoniers, tables, cupboards line the roadside. The markets have crashed; the word “antique” is increasingly anathema. “Vintage” is now substituted for “antique” in those fairs where period pieces were once sold.

I have looked at this brown study from a home-owner’s perspective, but then there is the various young generation’s perspective bought up on IKEA, where furniture is not decorative. It is purely utilitarian.

I remember when I was in a University College I took a Victorian vintage nursing chair into my study, because I thought it would provide a convenient place to rest to read a book or to just “crash”. I left it there when I left College. Initially, I regretted leaving it there. But time has confirmed the correctness of the decision. It would have been very expensive to store.

Maybe the nursing chair has remained in the College, souvenired, or more likely it has ended up as firewood, very much the fate of so much of this brown detritus from another Age. Years on, it may have survived awaiting to be recovered, a sombre counterpoint to the hedonistic modernism, a symbol of a world browning in the change in climate.

There is one solution that my wife has used. We had a very well- constructed mahogany chest of drawers, very chestnut. My grandparents had brought it back from Britain in 1919. Thus, it had lasted a long time. My wife decided she needed some storage and rather than throw out the solid brown chest and buy a new one she asked the painter to give it a distressed blue finish. He did an excellent job, and it now complements the back room, where an equally distressed painted bookcase faces it – but the aforementioned brown cedar desk still occupies one corner of the room, as a quiet reminder.

There is one solution that my wife has used. We had a very well- constructed mahogany chest of drawers, very chestnut. My grandparents had brought it back from Britain in 1919. Thus, it had lasted a long time. My wife decided she needed some storage and rather than throw out the solid brown chest and buy a new one she asked the painter to give it a distressed blue finish. He did an excellent job, and it now complements the back room, where an equally distressed painted bookcase faces it – but the aforementioned brown cedar desk still occupies one corner of the room, as a quiet reminder.

In Search of the Native Beech

Nestling hard against Tasmania’s Western Tiers, at the end of a gravel road winding through the tall eucalypts, is Habitat, a native plant nursery. We drove there after disembarking from the car ferry at Devonport. It is at the back of Deloraine on the other side of the Meander Valley. The Valley itself which was massively flooded at the same time last year was now brilliant green, its pastures covered by the dots of sheep. The ewes had been lambing prolifically. This tableau was Acadian, there being barely a cloud in the sky.

Our destination was near Liffey, but not on the road to the Liffey Falls. We were instructed to turn left and follow the bush road. Habitat appeared to blend with the bush, but this is where for 21 years they have harvested seeds and grown the plants from this seed.

They had closed their retail outlet earlier this year, now “growing to order” and have sufficient orders not to take any more until the end of 2024. Then the owner said she would be taking a “sabbatical” with her husband in 2025, and then they would be taking orders again from 2026.

Even though there is temperate rain forest at the bottom of their property, they had been ordered to evacuate their property because of nearby bush fires twice in the 21 years. They are in a high risk area with one narrow exit road lined by tall mountain ash and an understory of dense bush.

We were there to pick up five native deciduous beeches which we had ordered in March (and which I wrote up in an earlier blog). These had been left over from the previous year’s orders.

She said that the two most difficult plants to cultivate are the Tasmanian waratah and the native beech, which incidentally is the only native deciduous tree. In Strahan, there are numerous Tasmanian waratah bushes, all now in flower. So much for difficulty – once they like their surroundings.

But what of the beech?

She gave us tips about where to plant the slow growing beeches, in damp half shade, well-drained soil, and a protective wire cage around each to keep the wallabies away.

So here goes!

Rich with pollution – So much for Reducing Emissions

Need I editorialise …

Executives at Suffolk Construction have used the Boston-based company’s private jet nearly 250 times since last year to fly from Hanscom Field to destinations such as Aruba and Aspen, Barcelona and Rome, Martha’s Vineyard and Napa Valley, according to a new report.

Suffolk’s 19-passenger Gulfstream Aerospace GV-SP 550 flew every two or so days, its Rolls-Royce Pearl engines pumping out an estimated 2,329 tons of carbon emissions, the report said, which catalogued the climate pollution from flights to and from New England’s largest non-commercial airport. First appeared in the Boston Globe.

Mouse Whisper

There was recently an interview conducted by Michael Rowland, the personable ABC breakfast presenter. He was talking to the Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, who happened to be in Winton in the far west of Queensland. There is a certain irony of the symbolism – especially when the discussion turned to the Qantas decay.

Winton was the place where Qantas was founded in 1920, which meant it is the second oldest airline in the world. KLM, the Netherlands airline, was founded the year before.

Winton was also the site for the last commercial plane crash, when, as reported on 22 September 1966, an Ansett Vickers Viscount 832 aircraft on a scheduled flight from Mt Isa to Longreach caught on fire and crashed approximately 16 km from Winton, Queensland. It struck the ground at the edge of a clay pan and was immediately engulfed in flames, killing 20 passengers and four crew members.