There has been quite a deal of criticism levelled at the Prime Minister in attending the wedding of another Australian who has climbed out of an impoverished childhood to become a successful, charmless media personality, such that The Personality has developed a fan base, an armoury of sponsors and a wide variety of acquaintances, if not friends. If the Prime Minister feels comfortable among that mob, well does it matter?

As long as he feels comfortable amongst that crowd that should be all that matters; his bubbly happiness, cuddling a small child surrounded by colourful identities. After all, this scene will be balanced by his imminent exposure to the ermine and cope as he bows his head when his Monarch, Charles III, progresses past, he murmuring “I did but see him passing by and yet I’ll love him till I die”. Lovely to see Our Prime Minister so comfortable, in the presence of a monarchic inheritor of Colonial Exploitation. Once a Republican, always a Fawnling.

One may say that one is a centrist in that you have centralised fawning as a political objective; so that the “They” will say nice things about you in public; and ergo this will attract votes and assure that one has cemented the Party in government. John Howard, when he mentioned “relaxed and comfortable”, he meant he was just one of the mob, who just happened to live in the Prime Minister’s Lodge, but he governed from within the electorate rather than leading the country, as Keating tried to do.

The difficulty with those who lead and do it so publicly, as Keating did, is that the electorate has limited tolerance, manifested as the “tall poppy syndrome”. First used in the last century, it refers to the habit of one of the Kings of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, of hacking the heads off his subjects when they emerged too much above the Parapet of Achievement.

The difficulty with those who lead and do it so publicly, as Keating did, is that the electorate has limited tolerance, manifested as the “tall poppy syndrome”. First used in the last century, it refers to the habit of one of the Kings of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, of hacking the heads off his subjects when they emerged too much above the Parapet of Achievement.

As one commentator said about the syndrome “What ends up happening for some is they stop sharing their milestones with those whom they should feel comfortable confiding in, due to a fear of being resented, attacked or ostracised.”

Says it all. Thus, will Our Prime Minister return from his irrelevant trip as the Happy Prince? Has the fibro Monarchist emerged from his chrysalis of Disadvantage, a story of courage amid tears, to become such a contented enriched Icon?

Meanwhile build stadia not accommodation; open coal mines and sup with Santos, while supporting climate change by changing from summer to winter clobber; support a defence lobbyist industry while the poverty line is drilled further into single mothers and other disadvantaged; dine with News Ltd not The Guardian; let the Health system devised by his own Party in all its forms just wither while allowing the level of quackery blot out the cries of the sick.

Yes mate, I am glad you are laughing and happy clutching the baubles of Mediocrity – but you’re not forgetting your role as Head Elecutionist for The Voice.

Dampener on the Damper

The ABC with the engaging Tony Armstrong is presenting a nostalgic series about Australian customs. I remember when Peter Luck did a similar examination in This Fabulous Century in the late 1970’s. This 36-part series was superior in that the nostalgia was crisply presented. Nostalgia can become very boring and tiresome, and although Armstrong in many ways is very gifted, his charisma can sustain such an exercise for only so long. One segment which grated was the suggestion that the Aboriginal people were adept in bread making. The sooner Mr Pascoe’s Dark Emu is jettisoned the better; the photograph of him fondling a piece of native grass, as if it was the basis of the Aboriginal bakery industry, is patently wrong. The episode of Armstrong’s show sought to show Aboriginal people grinding native grasses; which they did in small amounts – hardly justifying this segment about the Aboriginal akin to a traditional baker.

Real damper is wheat based – flour, salt and water – developed by stockmen over a campfire; being simple, the ingredients could be rolled up in a swag and carried for long distances – as I found out, it was excellent with “cockie’s joy” or, as that was known by the whitefella non-cognoscenti, golden syrup.

I remember in Moorhouse’s book about the Burke and Wills expedition, “Coopers Creek”, a reference made to nardoo – seeds from a fern which the local Aboriginal people ground to form a type of primitive paste. However, there are some who say that nardoo is in fact toxic if improperly prepared, causing beri-beri, because it contains the enzyme thiaminase which destroys vitamin B1. There was never a bread industry, which is exemplified by the images in this latest documentary, which shows the grinding of seeds in a coolamon but never any resultant bread.

I remember in Moorhouse’s book about the Burke and Wills expedition, “Coopers Creek”, a reference made to nardoo – seeds from a fern which the local Aboriginal people ground to form a type of primitive paste. However, there are some who say that nardoo is in fact toxic if improperly prepared, causing beri-beri, because it contains the enzyme thiaminase which destroys vitamin B1. There was never a bread industry, which is exemplified by the images in this latest documentary, which shows the grinding of seeds in a coolamon but never any resultant bread.

The Dark Emu approach that the Aboriginals had all the wherewithal, not only the expertise but also the techniques before any other h. sapiens, belies the fact that the Aboriginal people did not need to ape the whitefella to remove any residual belief that they are inferior. Their culture evolved in a way which should not be destroyed by concocted stories. The Aboriginal people have had a unique place, and I’m afraid to see it lost in a litany of confected lore.

Phoenix Dutton?

When the Coalition lost the 1972 Federal election, some of the younger members of the business community who were linked by their employment in McKinsey’s decided that the Federal Liberal party should have a Policy Unit. Establishing a Policy Unit was more difficult and took more time than envisaged. Few people of any intellectual capacity who were establishing their careers were attracted to work for a political party which, although it had not lost by a landslide, was bereft of ideas and outdated in attitudes and behaviour embodied by their defeated Prime Minister, Billy McMahon. The other issue is that policy development is not pamphleteering and superficial slogans, but has to deal with the difficulty of tackling the slippery concept of equity, where the concepts of cost-efficiency, cost effectiveness and cost utility intersect.

Snedden’s office was thus thrust into being the Policy engine room during this first year of Opposition, where a Liberal Party Coalition inured to having a bureaucracy at its beck and call for 23 years no longer had that luxury. Yet the group of people Snedden almost accidentally brought together in his office, was a group of people which formed the nucleus of a de facto policy unit. Geoff Allen, his long-time Press Secretary, was the catalyst; he attracted good staff with the ability to think in terms of policy while understanding that policy has to be cast within the political framework of the “do-able”. Later, after a stint at the Business Council, Allen used his ability to set up a highly successful consultancy. He had an unerring eye for talent, and he was a great networker.

He and Snedden’s Private Secretary, Joan Thomson, were integral in my survival as the learning curve in such an office is almost vertical. My area of expertise was health and social policy. There is no doubt that there is value in working one’s way up the adviser chain, if the model is one of developing policy, preparing briefs and parliamentary questions/responses. In this function, John Goodfellow was the go-to-person in Snedden’s office – equated to being a Human Google. He was the epitome of that indispensable person that every parliamentary office should have. At this point it should be noted that our Office was spare in terms of staff numbers compared to the present.

Now I would advocate that every Opposition leader should hold governments to account; not by mindlessly harassing public servants nor living within a bubble of nastiness seeking to create dirt files as if the aim of politics is always one of anarchic destruction.

The policy development we accomplished in 1973, and the first months of 1974 before the Liberal Party policy unit swung into action, was crucial to the Liberal Party. For instance, as we neared the mid-year 1973, Snedden’s office through the work led by John Knight, later an ACT Senator, ensured that the Party had moved well away from McMahon’s railing mindlessly against China.

Snedden was welcomed to Beijing at a time when the Americans were making tentative steps towards full diplomatic recognition of China. It was prior to the Whitlam visit without there being any rancour from the Government. In fact, Stephen Fitzgerald, the first Australian ambassador to China could not have been more helpful. The Gang of Four was still in ascendency.

Unlike Whitlam, Snedden did not meet Mao Tse-Tung, but if we had stayed a day longer a meeting with Chou En-lai was in the offing. However, we needed to get to Tokyo to meet the then the Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka and travelling from Beijing to Tokyo at that time was not a simple matter. Instead of meeting Chou we were flying south to Guangzhou (then Canton) with the Chinese women’s volleyball team on board with us.

It had only taken six months for this major change in the Liberal Party attitude and policy to occur, remembering it was coupled with an acceptance of Australian troops being pulled out of Vietnam.

Richard Sheppard’s impact on policy directions also should not be underestimated, particularly on shaping the economic agenda, even though Snedden had been the Treasurer in the last Coalition Government. (Sheppard later became inter alia a senior executive at Macquarie Bank.)

For example, one writer identified a shift way from the protectionism, with which the National Country Party led by John McEwen had saddled the Coalition prior to 1973. Here the advice of Sheppard is discernible.

The Liberal Party agreed also that a more rational approach to policy making was essential. As Bill Snedden argued:

The economy, of course, must be seen as a whole in a modern economy. The different sectors are so closely linked that we could not afford to concentrate on one sector to the exclusion of all else (Commonwealth of Australia, 1973a: 2429).

Statements such as this represented a shift of emphasis away from agriculture as the key to Australia’s growth, towards a model of economy in which all industries were constructed as competing on a level playing field.

Compare the Liberal Party’s fortunes in the first year under Dutton running the Opposition agenda. Where is the policy agenda? In addition, to complete a disastrous year, Dutton lost the by-election for the former safe seat of Aston. By comparison, Snedden was successful in the retention of Parramatta, with Philip Ruddock’s election to the seat.

Perhaps, the lesson of that first year in 1973 is too far back in the ether for the current bunch of Liberal leaders to examine why that first year in Opposition under Snedden revived the Coalition and what could be learned by the current mob. Mistakes were subsequently made, including the election of the rurally-socialised Malcolm Fraser, but that is another chapter.

There is a Spook under the Mattress

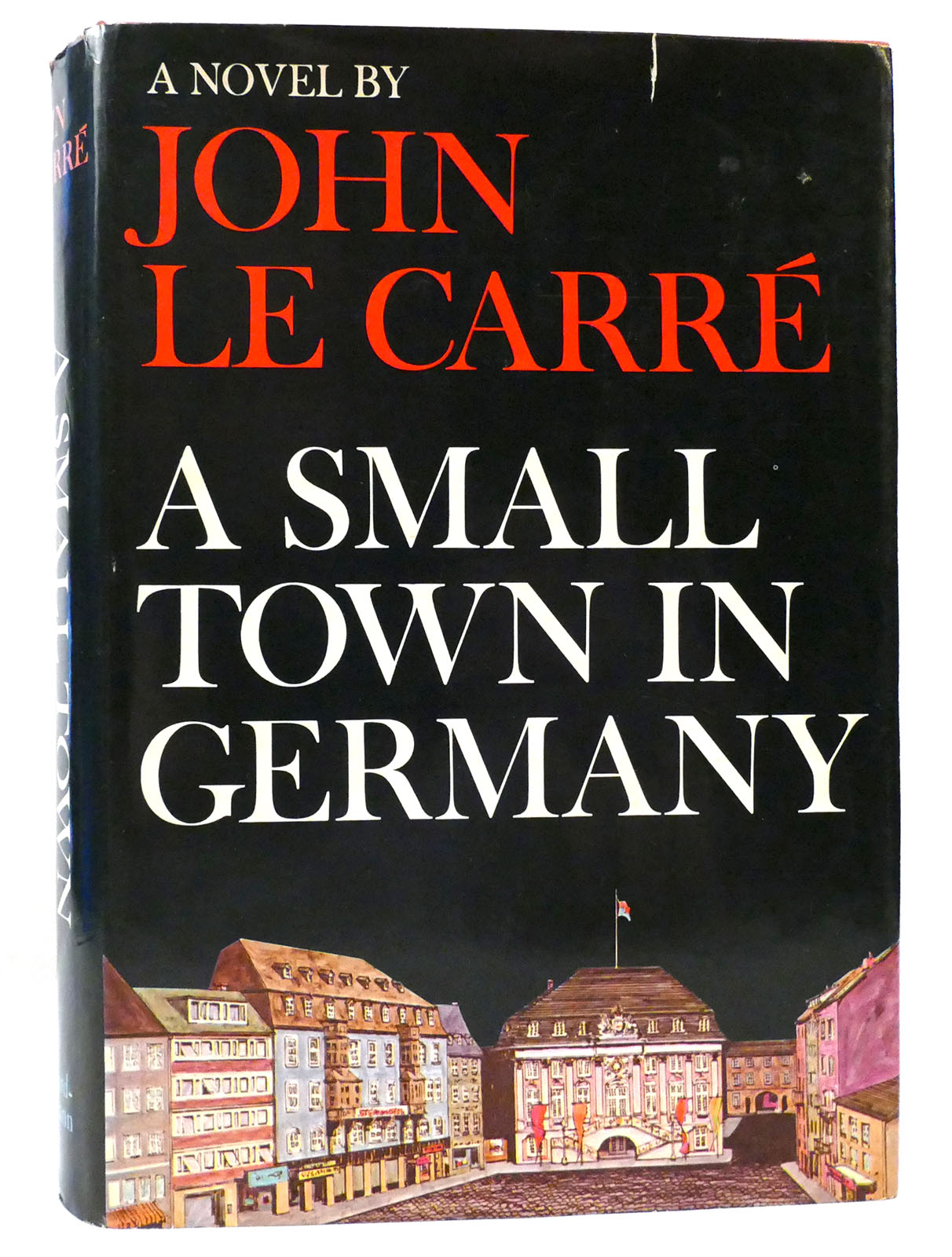

I’m reading A Small Town in Germany – one of the many spy novels written by John Le Carré, first published in 1968 at the height of the Cold War. Le Carré was in himself a man who worked in the spy industry, and his writing reflects the details which is a perfect definition of the tedium of the job. I have never been a devotee of Le Carré, although I recognise the perfect encapsulation of a group of mostly men, inured to deception and conspiracy.

I’m reading A Small Town in Germany – one of the many spy novels written by John Le Carré, first published in 1968 at the height of the Cold War. Le Carré was in himself a man who worked in the spy industry, and his writing reflects the details which is a perfect definition of the tedium of the job. I have never been a devotee of Le Carré, although I recognise the perfect encapsulation of a group of mostly men, inured to deception and conspiracy.

In two previous blogs I have briefly mentioned my glancing involvement in the world described by Le Carré.

I shared a study at Trinity College for one year with Sam Spry, well actually he was christened Ian Charles Fowell Spry, but acquired his nickname from Blamey; I forget why. We had been at school together and had been a moderately successful debating team. He did law while I undertook medicine. His father was Brigadier Charles Spry, who was the second Director-General of Australian Security Intelligence Organisation between 1950 and 1970. Spry was very much a Menzies man, a fervent anti-communist behind a bland genial exterior.

After I had been elected President of the University of Melbourne Student’s Representative Council, we were visited by three Russian students, who were doing a university circuit. It was a time when the Soviet Union supported the International Union of Students while the CIA funded other student organisations, including the World Assembly of Youth. I was thought to be radical within the student body because of the company I kept. Nevertheless, as I was not aligned with any political party I was seen to have the impeccable credentials of having been at both Melbourne Grammar and Trinity College, as well as consorting with the Brigadier’s son.

I suppose I should not have been surprised when I was approached by a fellow student, Peter Thwaites. He asked me whether I would like to meet his father, Michael Thwaites. In addition to his role as an intelligence officer and being a close confidant of Brigadier Spry, Thwaites was like many in intelligence, an intellectual, in his case an acclaimed poet. Like most intelligence officers, they could present an urbane front and after the usual preliminaries, he suggested that I meet with some of his operatives. I said OK.

The Theosophy building then was an unremarkable building in Collins Street, and it was arranged that we meet them there. I was greeted by a couple of men in grey and shown to a room on one of the upper levels. I remember how bare the room was – desk, chairs and nothing else. One of my companions opened a drawer and took out a newspaper cutting. The subject matter was the imminent visit of the Russian students, and would I like to report on their visit. Just an innocent request.

One of the problems I had with the Thwaites was their adherence to Moral Re-Armament with its overlay of the founder, Francis Buchman’s admiration for Hitler before WWII. From my point of view their association with Moral Re-Armament was enough. I always associated its outwardly clean cut image with that of the clean cut, cold shower camaraderie of Nazi Youth.

I thought about wandering into the world of espionage, and as I was to find out, Trinity College was a recruiting ground for ASIO. There was a particular night when a former senior student, who was “in his cups” gave a hilarious rendition of his life within ASIO, but we were all also in varying degrees of intoxication, and thus the next morning only the memory of this very engaging night remained.

I thought about wandering into the world of espionage, and as I was to find out, Trinity College was a recruiting ground for ASIO. There was a particular night when a former senior student, who was “in his cups” gave a hilarious rendition of his life within ASIO, but we were all also in varying degrees of intoxication, and thus the next morning only the memory of this very engaging night remained.

I never reported back. Sam believed that the “study” was just that – a monastic cell where you worked in silence broken only by small talk about share prices, where he was very successful player. A study was thus not a place for recreation; Sam always expressed his disapproval of my eclecticism not by direct confrontation but by decamping to the Baillieu Library to work.

After that year we barely communicated. He passed with honours, I negotiated the supplementary exam swamp successfully, but without magna cum laude. Our pathways totally diverged.

Yet, his experience left me with an intuitive grasp of this underworld in A Small Bulpaddock in Parkville. I would never know when there was a spook under the bed, but I would recognise it. Metaphorically, of course.

Still arguing. What was it with the Helix? An excerpt from The Boston Globe

The discovery of DNA’s double helix structure 70 years ago opened up a world of new science — and also sparked disputes over who contributed what and who deserves credit.

Much of the controversy comes from a central idea: that James Watson and Francis Crick, the first to figure out DNA’s shape, stole data from scientist Rosalind Franklin.

Now, two historians are suggesting that while parts of that story are accurate — Watson and Crick did rely on research from Franklin and her lab without their permission — Franklin was more a collaborator than just a victim. In the journal Nature, the historians say the two research teams were working in parallel toward solving the DNA puzzle and knew more about what the other team was doing than is widely believed.

“It’s much less dramatic,” said article author Matthew Cobb, a zoologist at the University of Manchester who is working on a biography of Crick. “It’s not a heist movie.”

The story dates back to the 1950s, when scientists were still working out how DNA’s pieces fit together.

Watson and Crick were working on modelling DNA’s shape at Cambridge University. Meanwhile, Franklin — an expert in X-ray imaging — was studying the molecules at King’s College in London, along with scientist Maurice Wilkins.

It was there that Franklin captured Photograph 51, an X-ray image showing DNA’s crisscross shape.

Then, the story gets tricky. In the version that’s often told, Watson was able to look at Photograph 51 during a visit to Franklin’s lab. According to the story Franklin hadn’t solved the structure, even months after making the image. But when Watson saw it, “he suddenly, instantly knew that it was a helix,” said author Nathaniel Comfort, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins University who is writing a biography of Watson.

Around the same time, the story goes, Crick also obtained a lab report that included Franklin’s data and used it without her consent.

And according to this story, these two “eureka moments” — both based on Franklin’s work — Watson and Crick “were able to go and solve the double helix in a few days,” Comfort said.

This “lore” came in part from Watson himself in his book “The Double Helix,” the historians say. But the historians suggest this was a “literary device” to make the story more exciting and understandable to lay readers.

After digging in Franklin’s archives, the historians found details that they say challenge this simplistic narrative — and suggest that Franklin contributed more than just one photograph along the way.

A draft of a Time magazine story from the time written “in consultation with Franklin,” but never published, described the work on DNA’s structure as a joint effort between the two groups. And a letter from one of Franklin’s colleagues suggested Franklin knew her research was being shared with Crick, authors said.

Taken together, this material suggests the four researchers were equal collaborators in the work, Comfort said. While there may have been some tensions, the scientists were sharing their findings more openly — not snatching them in secret.

“She deserves to be remembered not as the victim of the double helix, but as an equal contributor to the solution of the structure,” the authors conclude.

Howard Markel, a historian of medicine at the University of Michigan, said he’s not convinced by the updated story.

Markel — who wrote a book about the double helix discovery — believes that Franklin got “ripped off” by the others and they cut her out in part because she was a Jewish woman in a male-dominated field.

In the end, Franklin left her DNA work behind and went on to make other important discoveries in virus research, before dying of cancer at the age of 37. Four years later, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received a Nobel prize for their work on DNA’s structure.

Franklin wasn’t included in that honour. Posthumous Nobel prizes have always been extremely rare, and now aren’t allowed.

What exactly happened, and in what order, will likely never be known for sure. Crick and Wilkins both died in 2004. Watson, 95, could not be reached and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where he served as director, declined to comment on the paper.

But researchers agree Franklin’s work was critical for helping unravel DNA’s double helix shape — no matter how the story unfolded.

“How should she be remembered? As a great scientist who was an equal contributor to the process,” Markel said. “It should be called the Watson-Crick-Franklin model.”

The first response to such a conclusion is whatever happened to Maurice Wilkins in the model above? After all, he shared the Nobel Prize with Watson and Crick meeting. As for James Watson on his visit to Australia, briefly meeting him I thought him insufferable. Of the above players, he alone remains alive at 96, now virtually ostracised by the scientific communities because of his racist views.

Whatever the controversy, I for my part will be always a fan of Rosalind Franklin. Whatever the actual proportion of the discovery of the Double Helix, I’ll always believe that she was the victim of laboratory misogyny.

Mouse Whisper

Going against the grain? We mice are getting a bit edgy with those with whom we share this house. They are putting cinnamon on their cereal. What next? Cayenne pepper or peppermint. At least they will not use mothballs.