When I was around politics, our office had a regular visitor called Emil Delins. He was a Latvian-born journalist who was a strong supporter of the exiled Baltic countries – Estonia and Lithuania – being joined to Latvia in his advocacy mix. He was very polite, always articulate and fiercely anti-communist (and certainly anti-Russian).

Delins had graduated from a French Lycée in Riga one week before the Soviet occupation of Latvia in June 1940. The Russians then went on a selective elimination of Latvians, concentrating on the armed forces.

A year later it was the Germans’ turn to occupy the country, and a section of the Latvian people welcomed these new invaders; in fact they were numerous enough to create of division in the German army. Latvian Auxiliary Police battalions were raised from volunteers, the first sent to the front was involved in heavy fighting in June 1942 and acquitted itself well. Latvia however wanted to raise a Latvian Legion, under the command of Latvian officers, offering to raise an army of 100,000. In January 1943, Hitler agreed to the creation of the 15th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Latvian). These Latvian police units were deeply implicated in the massacre of 90,000 Latvian Jews and 2,000 Roma people.

A year later it was the Germans’ turn to occupy the country, and a section of the Latvian people welcomed these new invaders; in fact they were numerous enough to create of division in the German army. Latvian Auxiliary Police battalions were raised from volunteers, the first sent to the front was involved in heavy fighting in June 1942 and acquitted itself well. Latvia however wanted to raise a Latvian Legion, under the command of Latvian officers, offering to raise an army of 100,000. In January 1943, Hitler agreed to the creation of the 15th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Latvian). These Latvian police units were deeply implicated in the massacre of 90,000 Latvian Jews and 2,000 Roma people.

It was in the confused situation during the War, but Delins was able to spend time in university studies. Meanwhile, Latvia was occupied by the Germans, but then nearing 1945, the Russians were back, first occupying Estonia before moving towards Latvia. Along the coastline the German resistance, with Latvians involved, was successful in that it remained intact even on the day Germany surrendered, May 8th, 1945.

As such this battleground provided a conduit for Latvians fleeing the advancing Russians by enabling them to cross the Baltic to either Sweden or Germany. Presumably this was the route taken by the Delins family because he bobs up in Germany where there was a note that he undertook further graduate studies in politics. They were lucky in their choice; those who chose Sweden were deported back to the Russian or their Latvian communist allies.

The Delins family reached Australia in 1947.

Even though the number was relatively small, the impact of the Latvian immigrants on our country was vast. There was always the suspicion of migrants, especially the educated, that they were German sympathisers escaping the wrath of their now Russian-occupied country. As I had found out through personal contact, in any country which had been a battleground there was always a group of true believers in a free democratic country, but their problem was that they were the targets for both the committed communist and the committed national socialist.

I knew Delins was anti-Russian and passionately anti-communist. His advocacy did not convince Whitlam, whose government recognised that the three Baltic countries were legitimately part of Russia. Emil Delins’ advocacy outlasted the Whitlam decree, and the following year the new Fraser government reversed the decision of the then status quo.

One could detect the hidden hand of Emil Delins.

A further reflection

Despite his courtesy and surface good-naturedness, I always felt uncomfortable with anyone who was part of advocacy anti-communist groups. Delins detected that uneasiness in me, and on occasions he asked me questions designed to see how strong my sympathy was for his cause.

My problem with all these refugee groups, including those where the members had come from countries where there had been a strong collaboration with the Nazis, and especially those who were well spoken and articulate, was knowing to whom I was talking.

Not that Delins gave any suggestion of that, but in one conversation I did mention the similarity with Ireland and the centuries of oppression we had to endure at the hands of the British. But then what would he have made of one schooled in the best public school tradition? In a way my Irish ancestors collaborated as they worked for the British landowners. I always remember the disdain of the lady in the Clare Heritage & Genealogy centre in Corofin, when told that my ancestors were Egans from Clare but of the Church of Ireland. Egans from Clare not Catholics? Not possible. Nevertheless, that was the end of the conversation as I slunk off. I still can’t go back on the Egan side beyond the late 18th century. My great-great grandfather, John Egan, was a flour miller.

I have written about some of this Irish heritage before; the flour mill still stands on the river Inch. The Irish have been long oppressed; it has how I rationalised the advocacy of the Balts for their freedom.

The problem is that oppression is a very ambiguous word.

Tolarno’s – where we used “to get Shot” on Fridays.

Mentioning Latvians. I have known quite a few. One was Andris Saltups, who was then cardiology registrar at Prince Henry’s Hospital. He and myself, together with Jan Stockigt, who was a young doctor researching diabetes, regularly lunched together. Of these three blokes who went to lunch on Friday at the then recently-opened French restaurant Tolarno, I was the only one born in Australia – Jan/Jim in Germany with an Australian mother. Both Jim and his mother were caught in the crossfire fleeing from the Russian advance to escape from Germany.

We were all three mates in those days, in those far-off days of conformity we had ties with cannons on them to acknowledge the guys who got “shot” on Fridays. Andris, who had become Andy, was correct in a suit, Jan now transformed to Jim with a blazer; and Jack, once known as John, in an ageing stained sports jacket. Probably a bit formal by today’s standards.

Tolarno had a whiff of the exotic, even if our semi-jock doctor image did not quite fit the bill. The plat de jour and the red wine did.

The walls were covered with distinctive murals – distinctive faces – bit spooky I thought.

The documentary on Mirka Mora reminded me of those days in the 60s when both the Moras were in full flight. There was something exotic about a French restaurant. Drinking wine for me had become a relatively recent habit, for I grew up in a world of sherry and whisky; with perhaps a touch of Drambuie, crème de menthe or chartreuse after dinner. What is so everyday was new, and the Moras were in the forefront. Not that we fitted into the arty-crafty school. Georges would acknowledge us because we regulars were often engulfed in hilarity, but his loquacious wife Mirka had difficulty finding an opening to talk to us, but perhaps we were not interesting enough. Understandable.

Prince Henry’s hospital is no more. Georges and Mirka split. Tolarno survived under Leon Massoni, whose family had owned Florentino’s, then the posh signature restaurant in the City.

Eventually, Jim Stockigt went off to California to work with Ed Biglieri, a research scientist /clinician. I remember just before Jim went that he made sure that he had a very short haircut, because haircuts were reputed to be expensive in America. Jim came from a musical family and was a highly skilled bassoonist.

Andy Saltups was friendly with my wife, as both were refugees, and I think the parents knew one another somehow. We saw him socially quite often as he was, for a time, very close with one of my then wife’s friends.

The lunches at Tolarno were a tiny wedge in one’s life. After lunch we would occasionally go down the hall to the Gallery, but there was only so much to see, and it seemed an extension of the murals which adorned the restaurant.

Over the years, I saw Jim twice more after he came back from America, the last just before he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The promise to catch up was there, but in this case Fate intervened.

As for Andy, when I left Prince Henry’s the link was broken – too little remained common. He stayed there as a specialist cardiologist. I have not seen him in 50 years. Prince Henry’s closed in 1991 and is now the “Melburnian”, a high-priced apartment building.

As I watched the Mirka Mora documentary, Tolarno was mentioned more in the context of the gallery and her paintings rather than the Moras’ influence on Melbourne’s dining habits. Understandable, given the bias of the documentary.

When we lunched at Tolarno, Mirka was always there. She had a dark uncommon beauty then, suggestive of Leslie Caron. I was disturbed by the documentary. What was presented in the documentary were people remembering their link with an elderly Mirka. There is a fine line between description of idiosyncrasy and that of pathology.

What I found most disturbing was the story of this woman seeing Mirka in what was probably 2005, sitting at the far end of the Georges’ tearoom. Georges was a department store which epitomised the Melbourne couture, a magnet for the well-connected or those who wished to be. However, even such a beacon of detached privilege was on its last pegs at that time.

This woman, who knew Mirka, recounted staring at the solitary figure who had a giant éclair in front of her. Once Mirka knew she had an audience, she promptly stuffed the whole éclair into her mouth, so that cream smeared her cheeks and chin. One enormous ingestion. The watcher thought it was a supreme example of Mirka’s humour; whereas I felt a sense of sadness. Had she come to this! The documentary was riddled with stories of her artistic attainments, her generosity, her sense of the ridiculous, her love of children as she aged. Yet that image of stuffing her mouth with an éclair stuck.

Sometimes I wonder whether the sense of the ridiculous, playing the fool, should not be translated into self-loathing. I have no right in one way to make a judgement on Mirka Mora, but then the documentary watchers did not see her in a newly-opened Tolarno in 1967. The documentary brushed over that time, and once you document a person then there should be nowhere to hide such crucial subject matter.

But for good or ill, it provided me with an opportunity to remember an uncommon time, which would become all too common as Australia emerged from its wartime monochrome and we talked endlessly about “multi-cultural”.

The woman who should have been awarded two Nobel Prizes

Janine Sargeant. Guest Contributor

In the week when Kate Jenkins, Australia’s Sex Discrimination Commissioner, released her report on the “frat house” culture (as described in The New York Times) of Australia’s Parliament House and the generally bad behaviour there, a revealing book on work culture and the treatment of women in another era has been reviewed in The Guardian Weekly.

For those of us who know Rosalind Franklin’s story, the book just serves to further highlight the appalling behaviour of her fellow researchers. For those who don’t, we are talking about the discovery of DNA.

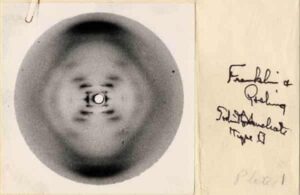

Rosalind Franklin was a graduate of Cambridge University, a chemist and X-ray crystallographer. She discovered the key properties of DNA, which led to the correct description of its double helix. Specifically, it was her work on the X-ray diffraction images of DNA, particularly “Photo 51”, that led to the discovery of the double helix.

Her colleagues, Francis Crick and James Watson not only appropriated her research findings as their own but hogged the limelight without any attribution to Franklin.

The reason? Franklin’s “Photo 51” was handed to Watson by a colleague, which led Watson to redo his 3D modelling and it was another piece of Franklin’s work that similarly led Crick towards “their” scientific discovery of a lifetime.

The book, The Secret of Life, by Howard Markel, condemns all the men involved, but singled out Crick and Watson whose “lack of a formal citation (in their historic paper for Nature) of Franklin’s contribution … is the most egregious example of their negligence”. Negligence? No, that word implies omission; this was a sin of commission – they deliberately excluded Franklin. Watson has been described as having many strong prejudices, but perhaps Franklin’s greatest sin was simply to be a woman in a man’s laboratory.

In his book, Markel went on to paint a picture of a culture of misogyny and egotism that punished Franklin for personality flaws that in her male colleagues were tolerated.

Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins – who had given Franklin’s “Photograph 51” to Watson – shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for “their discovery of the molecular structure of DNA, which helped solve one of the most important of all biological riddles”.

Nobel rules now prohibit posthumous nominations (although this statute was not formally in effect until 1974) or splitting of the Prizes more than three ways, which perhaps makes the omission of Franklin all the more egregious. Easier to just ignore Franklin’s contribution. Apparently in 2018, Watson still remained outraged at the suggestion that Franklin might have shared the Nobel Prize, although he acknowledged that his actions with regard to Franklin were “not exactly honourable”. Too little, too late.

But there’s more: after a disagreement with colleague Watson and the Research Director, John Randall, in 1953 Franklin had moved to Birbeck College at the University of London, a public research institution and much of her work done on DNA, including her crystallographic calculations was then just handed over to Wilkins.

At Birbeck, again using X-ray crystallography, Franklin led pioneering work on the molecular structures of viruses. At that time her findings were in direct contradiction to the ideas of the then eminent virologist Norman Pirie – it was her observations that ultimately proved correct.

In 1958, on the day before Franklin was to unveil what would now be excitedly announced as “a significant research finding” on the structure of tobacco mosaic virus, an RNA virus, at an international fair in Brussels, she died of ovarian cancer at the age of 37. Her team member, Aaron Klug, continued her research and he went on to become the sole winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982 “for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biologically important nucleic acid-protein complexes”. This work was exactly what Franklin had started and which she introduced to Klug; she should have shared that Nobel Prize too.

Rosalind Franklin was never nominated for a Nobel Prize. Her early death meant awkward decisions about including a woman as one of the nominees didn’t have to be made.

An interesting endnote: on 28 February 1953, Watson and Crick felt they had solved the problem of DNA enough for Crick to proclaim at The Eagle, a local pub in Cambridge, that they had “found the secret of life”.

Watson and Crick did not cite the X-ray diffraction work of Wilkins and Franklin in their original paper, although they apparently admitted having “been stimulated by a knowledge of the general nature of the unpublished experimental results and ideas of Dr MHF Wilkins, Dr RE Franklin and their co-workers at King’s College London”. In fact, Watson and Crick cited no experimental data at all in support of their DNA model. Franklin and Gosling’s publication of the DNA X-ray image, in the same issue of Nature, served as the principal evidence. So just whose “secret of life” was it that Watson and Crick were announcing?

(In the past 25 years there has been a catch up, with a plethora of recognition and awards, including a TV movie, two documentaries and three plays; the Boat Club of Franklin’s alma mater Newnham College Cambridge launched a new racing VIII, naming it the Rosalind Franklin, and in 2005, the DNA sculpture (which was donated by James Watson) outside Clare College Cambridge, incorporates the words “The double helix model was supported by the work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins” – elementary Dr Watson). James Watson is now 93 but it is not too late for him to acknowledge the actual role of Rosalind Franklin; he was absorbed into the same British research establishment mores that also distorted Alexander Fleming’s actual minimal contribution to penicillin research. This still did not impede Fleming sharing the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, whereas it should have gone to another.

Happy Hannukah

Latkes are deep-fried potato pancakes and are a traditional food of Hanukkah, but reporter Tamara Keith couldn’t figure out how to make them, even with the help of her mother-in-law’s recipe. After spending some time in the kitchen with her mother-in-law, she learned that the recipe was to blame

Latkes are deep-fried potato pancakes and are a traditional food of Hanukkah, but reporter Tamara Keith couldn’t figure out how to make them, even with the help of her mother-in-law’s recipe. After spending some time in the kitchen with her mother-in-law, she learned that the recipe was to blame

TAMARA: When I was converting to Judaism, my rabbi strongly recommended that I buy some cookbooks. It seems part of learning to be Jewish was learning to cook Jewish foods. Growing up Methodist in a small town, my first introduction to latkes was in college after I met my boyfriend, Ira. The potato pancakes Ira’s mom Andrea and sister Shannon made were terrific. Crispy and warm, dunked in apple sauce for that perfect balance of grease and fruit.

I asked for the recipe and Andrea photocopied a page from a paperback cookbook. The next year at Hanukkah, I followed the recipe exactly but the latkes came out all wrong, like over-crisp hash browns. Failure after failure led me to Manishevitz instant latkes. Just add eggs. It’s like defeat in a box. Ira and I are married now, so it finally seemed okay to go back to my now my mother-in-law and ask her what I had been doing wrong. The first step is easy, peeling the potatoes.

And then what comes next?

ANDREA, her Jewish Mother-in-Law: Next we have to grate the potatoes the proper amount of smoothness and roughness. They have to be smoother than hash browns, but we don’t want them to be completely mushy.

TAMARA: Which none of this is actually in the recipe.

ANDREA: No.

TAMARA: The whole consistency thing.

ANDREA: This is the magic of Jewish tradition and family tradition.

Hannukah occurs in December. In the second century BCE, against all odds, a small band of faithful but poorly-armed Jews, led by Judah the Maccabee, defeated their Syrian-Greek rulers, drove them from the Holy land, reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and rededicated it to the service of Jehovah.

When they wanted to light the Temple’s Menorah (the seven-branched candelabrum), they found only a single pot of olive oil that had escaped contamination by the Greeks. Miraculously, they lit the menorah and this single pot of oil lasted for eight days, until new oil could be prepared with ritual purity.

When they wanted to light the Temple’s Menorah (the seven-branched candelabrum), they found only a single pot of olive oil that had escaped contamination by the Greeks. Miraculously, they lit the menorah and this single pot of oil lasted for eight days, until new oil could be prepared with ritual purity.

To commemorate and publicise these miracles, the festival of Hannukah was begat.

There is thus no possible connection with the Christian Christmas apart from the timing, and in a season of presents, one tradition of Hannukah is giving money to children. But once it arrives, the insidious euphoria of commercialism can overwhelm any religious significance.

Christians undertake an annual ritual engorgement around Christmas Day, presumably to counterpoint the meagre circumstances of the Bethlehem birth. Hannukah, because of the oil association, is a festival of the deep fried, as the description of Jewish potato cakes above attests.

Hannukah does not make the same impression on our community as it does in the United States. My attention nevertheless was directed to an article lamenting how Hannukah had been polluted by some of the impedimenta of Christmas.

This article in the Washington Post bemoaned the creeping tendency of Hannukah to be converted into a Jewish Christmas, where it is in fact one of the lesser Jewish holiday periods, and in the eyes of the author of this piece, acknowledging Hannukah could be as simple as lighting the menorah and let its light shine for eight days.

He describes a recent trip to a large retailer where he spotted the following abominations: a festive tray featuring four minuscule bearded dudes, their hats decorated with dreidels, above the phrase “Rollin’ With My Gnomies”; a throw pillow, in the blue-and-white color scheme of the Israeli flag, stitched with the phrase “Oy to the World”; an assortment of elves, sporting Jewish stars and looking like they belonged more in a Brooklyn yeshiva than anywhere near the North Pole; and a set of three kitchen towels with the truly baffling wording, “Peace Love & Latkes”.

There is not much more to add, except for you, the reader to contemplate the Mouse’s Whisper this week. It is not only Hannukah, that Mammon defiles.

A Card from Our Seychellois Friends

This week we received a Christmas card from Michael and Heather Adams. Isn’t it so quaint to receive Christmas cards, especially from a family in the Seychelles.

We visited the Seychelles over 30 years ago, and it was the last leg of our African tour, which in that Apartheid period excluded South Africa. Qantas then flew to Harare in Zimbabwe, where we disembarked and roamed through a number of countries, including climbing Kilimanjaro and succumbing to malaria in Madagascar. Seychelles was the place to recuperate. We flew to the main island Mahé and stayed in the capital Victoria.

The Seychelles was once uninhabited and the first Europeans to sight the main island was Vasco da Gama. It later became a matter of disputed acquisition, between the United Kingdom and France. In this case, the UK were the winners, but there has remained a strong French influence. Once the Seychelles was settled, there inevitably were slaves, emancipated in 1835, from whom the Creole culture has emerged.

It should be recognised that Seychelles has a huge footprint across the Indian Ocean – 115 islands, of which only eight are inhabited, but it had to wait until 1903 to gain a separate existence from Mauritius.

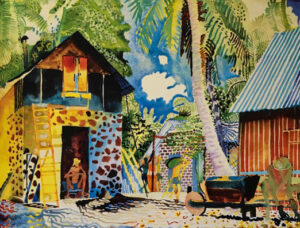

At one stage during this stay, we ended up driving down this gravel roadway and coming up to a picture book wooden house set in this tropical backdrop, which spilt across the house itself. This was the home of Heather and Michael Adams. The home was on Anse des Poules Bleues and, it is said, true to the name of the Bay, the family had bluish hens which laid blue eggs.

Michael seems to have recently acquired a knighthood, which is not surprising given the high regard for his skill in silk screening, its composition and his depiction of his Idyll. He has been in Seychelles since 1972 and recently has said that he intended staying there. He had grown up in England and is said to have been inspired by the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall, at a time when the garden was a wild unkempt neglected “lost garden”.

Heather had been in Kenya when they met after he left Uganda to get away from Idi Amin, and they married. They have two talented children, both artists, both having learnt the silk screening skills according to the latest Christmas card, all still in the Seychelles. Their names are Tristan and Alyssa.

When we stumbled upon his gallery, we were absolutely blown away by the complexity, yet a compelling simplicity of the lines of colours; colour which overwhelmed us when we entered his studio.

We bought some of Michael’s works, including a large screen print which adorns the wall, and required more than 20 screens. His works are so reflective of his perspective, of a person awash in the joy and yet serenity of his Seychellois life. No wonder that he has been likened to Paul Gauguin. One in French Polynesia; one in the French diaspora of the Indian Ocean.

I recently purchased one of his silk screens for one of our sons for his half-century, which has pride of place in his home in Melbourne.

Otherwise, the intention has always been to go back to the Seychelles, but we haven’t. For Australians it is off the beaten track. The Seychelles may be the playground of the wealthy Europeans; it may sit uneasily off the African coast where Somali pirates have recently roamed the archipelago. To see the giant Aldabra tortoises, reputedly the oldest one being about 190 years old, but apparently exiled to St Helena – a testudineous Bonaparte.

Yet every time the Adams family Christmas card arrives, it stirred the intention to return. But with the intervening years since 1990 when we were there, the intention has burned lower as age entangled us.

This year, the watercolour painting of copra workers of the Botanical Gardens reflects the time he and Heather had just arrived in the Seychelles – 1973.

But to emphasise how determined the continuation of this exchange has been with us and others, whether for such a period of time, on the bottom of the card is printed:

“Apologies if you did not receive Christmas cards last year from us but due to Covid, our Post Office was closed for most of the year and no post was accepted to most countries.”

Our card to them this year will be emailed.

James Pindell has a few questions to answer

James Pindell is a bespectacled unremarkable looking graduate of the School of Journalism at Columbia University. He could be anybody’s journo at that Press Conference. Yet he is a political reporter for the Boston Globe, which lifts his ranking. He posed these questions on November 26.

He sets out three questions about Biden and provides commentary rather than answers.

Question 1: But why wouldn’t Biden run?

Very few American presidents have openly taken re-election off the table: One of them, James K. Polk, announced it the moment he received his party’s presidential nomination in 1844. His decision was part ideological — as a believer in limited government power — and practical: agreeing to only serve one term was likely the only way he could build a coalition of party power brokers to back him for the nomination.

Biden has different issues. The reason people talk about him serving only one term is largely due to his age. At 78, he was the oldest person ever elected to serve as president in 2020. He could break that record if he ran again in 2024 at age 82.

Mental and physical capacity to serve as the leader of the free world is something that voters must determine for themselves. While plenty of data is available from Biden’s doctors, it is still a subjective decision by every voter in how to read the data.

But lately, there is a second reason that people, including Democrats, are asking whether Biden will run: his poor poll numbers.

Now 10 months into his presidency, Biden’s approval ratings have never been this low. A Marist poll out on Wednesday showed him at just 42 percent, in line with other recent polls. This means Biden is the most unpopular president at this point in his presidency, other than Donald Trump.

Question 2: Can anyone other than Biden win?

Aides have already signalled in anonymous quotes to the press that if Biden does run it might be out of a sense of duty. The 2020 election turned out to be much closer than Democrats thought it would be. It is possible that among all the Democrats who ran in the 2020 primary — the most diverse field in history and one of the largest — only Biden could have defeated Trump for re-election.

With Trump looking more likely than not to run again, the Trump factor is not off the table. And the field of potential candidates is basically the same crew that ran in 2020.

And, yes, if Biden doesn’t run it likely would be a crew. The most obvious heir apparent to Biden, his vice president Kamala Harris, had a 28 percent approval rating in one recent poll.

This has led to open speculation, even this week, that Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg could run. Buttigieg would not only be among the youngest people to be elected president, but also the first openly gay person.

Let’s be clear here: Even after winning the Iowa Caucuses and coming in a close second in the New Hampshire primary, the Democratic electorate didn’t think Buttigieg could win (or that he sufficiently understood the Black vote). It is unclear whether a stint as transportation secretary would change that.

Question 3: If Biden doesn’t run how badly will tensions within the party explode?

As anyone could see during the Democratic presidential primary season or witness this year during negotiations over infrastructure and “Build Back Better” legislation, there is a lot of tension within the party.

The party’s base has moved left and wants leaders who are not old white men. There is also an establishment, led by Biden and South Carolina Representative James Clyburn, who feel like they are more in tune with Democrats and the electorate as a whole.

That next year the Republicans could win big because of Biden, prompting Biden and his allies to say that only proves that Biden has to run, is the conundrum.

Having read the questions, let me answer them in my normal ‘umble way.

- When you get to 80, it is not the new 60.

- I doubt whether Kamala Harris has the firepower. I have always been a fan of Amy Klobucher, but the question is, will Biden survive 2022 (and for that matter will Trump)?

- Chissà!

The Pindell article could now be subject to the “Omicron-scope”. A great deal can happen in a day or two while the Virus stalks, changes its clothes and attacks again. After all, he did write this opinion piece in the Pre-Omicron Age.

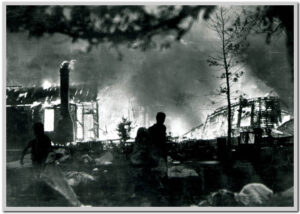

Mouse Whisper

Black Friday 1939

Fire sale. Damaged goods at a generous discount.