When the Defence Department advertise for recruits their first message is not that you are liable to be killed. However, when the rural medical profession wants to send a message, it uses the equivalent negative message as though rural medical practice is so hard that inevitably you will burn out under the weight of patients – an isolated martyr on the cross of medicine in the vastness of this Land.

I firmly hold the opinion that all medical graduates should be fully licensed to practice on graduation. After all, what is the long undergraduate program there for, and the intern year should fully provide the opportunity to develop the skills necessary to not only deal with emergencies but also to recognise emergencies. The importance of collegiality is to recognise when you are out of your depth in dealing with an emergency and to not fear calling for support as if making a mistake is a felony, because we all do make errors. The earlier that recognition, the better for you, and moreover more importantly for your patient.

I graduated long ago when the profession was predominantly male, but my first wife was in the same year and I viewed the misogynistic remarks, the discrimination, and in one case undue professorial interest towards her, which would be completely unacceptable today. She was diminutive and beautiful, but when one drunken medical student tried to molest her, she flattened him with a punch which would have done justice to any featherweight champion.

It was a more uncomplicated time for men, but not so for women. Medicine had not differentiated, and there was a defined route to general practice. In first year residency now renamed “intern”, it was when, in my outer urban hospital, there were medical, surgical, and in the emergency department, three month rotations. The other rotation was ENT, at a time when if you survived childhood with your tonsils intact, you were lucky. I and my companion resident medical officers were presumed to be destined for general practice.

Tonsillectomy was then common, and it was one technique that the general practitioner, who wanted to be competent as a surgeon, needed to master. Even in the teaching hospital, the intern developed skills, saw more patients then, so that by the end of first year, one accepted that life as a doctor was not part-time and “quality of life” was a secondary consideration. Moreover, as a young graduate one got used to the night call; it was part of the implicit social contract with the community.

Thus, the hospital residency was concerned with acquiring skills but also reconciled to responsibility being a doctor entailed. One had to do a year at the Women’s Hospital and a year at the Children’s Hospital as part of general practitioner training. There was an optional year in the general hospital where anaesthetic skills were consolidated and there was a further opportunity to improve procedural skills. There was no examination if you wanted to be a general practitioner. Your credentials were your references gained from what you had done in your three or four first post-graduate years.

Since those times, an accepted course unencumbered by bureaucratic regulation, which provided a recipe for procedural general practice, has all but disappeared. It should be emphasised that the medical staff within the hospital, either salaried or “honorary” had a strong commitment to teaching, not going missing and “skiving” off into private practice or the research laboratory.

The immediate response to this is that it’s an exercise in nostalgia for a long past professional development, unencumbered by the strangulation of bureaucracy enacted by governments with no knowledge of medicine. The profession bears the blame to some extent, relying on the mysteries of medical care leading to a gross asymmetry in the amount of information available to the community in an understandable form.

When I graduated, the profession was basking in the glow of the discovery of antibiotics and the Sabin oral polio vaccine. Investment in medical research followed. I spent five years in the Monash Department of Medicine undertaking both a Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Philosophy, a case of excessive “diplomatosis” in modern terms. My research scholarship paid a pittance which meant I had to do a variety of professional jobs including general practice, working for the Army (it being the time of the Vietnam War), examining conscripts for fitness to serve, and tutoring medical students and junior medical staff.

Medical research to me was inspirational, but then I was working with some great scientific minds, far better than myself. Because of this environment, I was fortunate and my research, although mediocre, helped to elucidate the role of angiotensin in causing hypertension. One of the results of all research worldwide in this area were more effective drugs, among the most important discoveries of the twentieth century. The growth of the pharmaceutical companies with the need to discover drugs to maintain their viability resulted in the rise in the cost of medicines. Similarly, the improvement in the tools created a tribal approach as distinct subspecialties grew around each of these totems. For general practice surgeons, the rise of laparoscopic surgery was just one reason for the demise of the general practitioner surgeon, whose techniques became more and more obsolete when distanced from new lesser invasive techniques. Post-procedural morbidity in turn diminished.

The other factor was the growth of the emergency medicine specialty. I am not the only one to believe this was one of the detriments to medical practice. They are essentially able to resuscitate patients, which was once the domain of the general practitioner. But they have no collegiality, they are essentially medical gypsies, working set hours and providing an easy but expensive substitute in regional and rural Australia, working hospitals divorced from the community. They have no community identity and are only a locus along the ongoing care. Unlike the general practitioner, they deal with “objects” for treatment and some are undoubtedly very good, but in the end they never have long term patient relationships. Personally, I think the whole emergency doctor profession needs a detailed review, but unfortunately that will never happen. They are too entrenched, and unless there is some modification in attitudes, rural general practice will continue to suffer.

If one ignores these elements in bold below, then rural general practice will always languish. The concept of one doctor being able to be on call 24/7 is a prescription for burn out. Any medical practice in any township should not be less than three doctors; and four would be preferred. The problem of what I would classify combatting the element of isolation is often the enmity between neighbouring towns, the closer they are geographically it increases. Thus, constructing a setting where four doctors serve multiple townships is harder than it seems.

Another factor I have observed and about which I have never varied my opinion the more I was exposed to rural practice is social dislocation by which I mean where your spouse does not want to come or where you need to send the children away to school.

Then there was the question of being able to be accepted by the community in which one practises. There are many flash points which challenge the third element, community tolerance, by which as I have explained in the past is the ability to get on with the community you serve. Conflict between health professionals and then within the community must be resolved and not turned into a chronic festering situation. I’ve observed that, and it greatly hinders recruitment.

The fourth element is succession planning which is poorly done, but it is so important that it deserves a cohort of skilled people who can help the doctors to recognise their professional mortality but also that the length of service in a practice should be considered in five-year aliquots.

Money by itself is not an incentive; and importing doctors without sensitive planning can be disastrous. In the next part, I’ll discuss what works and how neglect, dissonance and dysfunction have crept into the system.

At the head of this piece is a photograph of a place where I have been several times. On the coast in the Far East, the border separates two large urban areas, Coolangatta (Queensland) from Tweed Heads (NSW). Pictured is the Warri Gate, on the Far West border – a gap in the dog fence that separates from Queensland from NSW, where there is no settlement, only a gibber plain that stretches northwards. The nearest settlement is the NSW speck, Tibooburra where the Silver City Highway ends. That is Outback Australia – silent ground covered with Sturt desert varnish. The only companion, a kangaroo watching us intently.

“Delay, Deny, Die” – The Diggers’ Cry

When I had only just turned fourteen at the end of 1953, I got my first job assembling medical files of returned servicemen (service women were rare) in the then Repatriation Department. My boss, I remember, was a very nice guy called Paddy Saxon. He, like most public servants, was a returned serviceman. He had served in WWI, was nearing retirement and had already signed off. The unassembled medical files had built up despite there being allocated overtime to deal with them. The chap whose responsibility it was for the files spent most of the day staring out the window and assembling files very slowly and in silence. He too had been an ex-WWI “digger” and it was a time when cognitive loss was just “old age”.

Reading the huge delays and the time needed to train persons in the current Veterans’ Department in assessing claims reminded me of my holiday job within the Department divided by those who took a positive view towards the returned servicemen’s claims and those who were inherently suspicious of any claims.

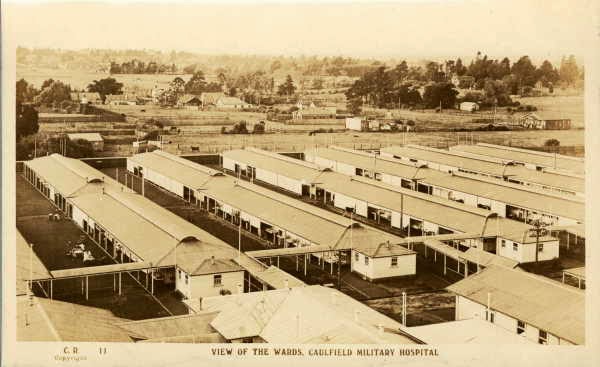

The reason that I knew about this difference in approach was by listening to my father, who was a doctor within the Department. He worked on the basis that those who had fought for Australia deserved compensation, unless otherwise indicated. He had served in the Navy during WWII, which interrupted his graduation as a doctor. This occurred in 1946 after which he undertook his first-year residency working at the Caulfield Repatriation Hospital from which he moved to becoming a salaried medical officer within the Department.

Before the War, he had graduated in both commerce and law, and like many such graduates, the Great Depression truncated his career prospects, and at my mother’s urging he started a medical course in 1935-6. Information about this progress is somewhat murky, but he rubbed the Professor of Obstetrics up the wrong way to such an extent that he was consistently failed, a situation which would be impossible these days – but that is another story.

Nevertheless, the legacy he left with me was a sense of confronting injustice, and with his armament of experience, he was a formidable champion of the diggers.

It is thus interesting to read about what now has been occurring in the Veterans’ Department, the successor to the Repatriation Department. There was a far greater load of claimants in his time, and he increased his irritant role in the Department by being the national Secretary of the Repatriation Medical Officer’s Association. He thus wielded substantial hidden influence.

I would suggest that if he had been in full flight these days he would have been very vocal over the behaviour of the previous Morrison Government in delaying the $6.5 billion being allocated, but then he had the returned servicemen backing him up. The Department found his forthright advocacy an irritant at the best of times, but he got things done.

As it was, as has been in reported some detail in the Melbourne Age,

In 2018, Scott Morrison said he understood “first-hand the battles so many veterans face when they leave the defence forces”, and argued that as a nation, more could always be done to recognise the men and women who had served in uniform. Unfortunately, that didn’t extend to processing veterans’ entitlement claims.

By April 2023, the average processing time for a veteran’s claim was 435 days, while 36,271 claims – almost half of those lodged – hadn’t even been looked at (known as “unallocated” cases).

This was a known and growing issue for the Coalition. In March 2022, then veterans’ affairs minister Andrew Gee threatened to resign unless extra money was put aside to clear the backlog, of 60,000 unallocated cases, veterans looking at their claim for financial support.

Morrison’s government employed outsiders through labour hire companies without any knowledge of what was required. Given the track record of government, somebody in the appointment chain may have received “a brown bag” with orders to obfuscate the claims process. Switching back to public service employees to undertake the work, by the Labor Government, the backlog of unallocated cases has reduced to just 2,569 and the processing waiting time, while still far too long, has dropped by 62 days. Staff has been increased.

In the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, it is said it takes up to six months to train the specialist staff responsible for overseeing claims. And so the previous government’s use of labour hire ended up being a disaster for the Department and veterans. Still, I find a six-month training program to be somewhat excessive.

The Age article goes on to praise Minister Keogh, Treasurer Chalmers, and Finance Minister Gallagher for clearing up this backlog “without fanfare”. In addition, they’ve made a conscious decision not to politicise a situation which was an absolute mess and ripe for point scoring and public criticism.

What is depressing is the lack of champions for the “diggers” within the Department, and the fact that the RSL has been strangely quiet, given there are 20,000 returned servicemen from Iraq and Afghanistan; and the Vietnam war veterans are now well and truly in the ranks of the elderly. However traditionally, this Department has not attracted the top grade bureaucrats, and moreover does not attract attention unless there is a Morrison – in other words “grandiose announcements and then stuff-up cloaked in religiosity”.

Also, when I was working for Repatriation Department, I assembled all the outstanding medical files, including the backlog, in less than a month. So much so that my supervisor told me to slow down. Instead, once I had no files to assemble in my in-tray, I went into the rooms where the medical files were kept, and with the enthusiasm of youth assembled the files of several high ranked officers not knowing if I was transgressing any regulation. In any event nobody stopped me. I was amused when I encountered what amounted to the brown hard back medical record. This was the venereal disease record, and there was no way this could be missed. It was an early introduction to my eventual medical career.

Also, when I was working for Repatriation Department, I assembled all the outstanding medical files, including the backlog, in less than a month. So much so that my supervisor told me to slow down. Instead, once I had no files to assemble in my in-tray, I went into the rooms where the medical files were kept, and with the enthusiasm of youth assembled the files of several high ranked officers not knowing if I was transgressing any regulation. In any event nobody stopped me. I was amused when I encountered what amounted to the brown hard back medical record. This was the venereal disease record, and there was no way this could be missed. It was an early introduction to my eventual medical career.

Not what it seems

The NSW Branch of the Australian Medical Association announced last Friday an exclusive offer of premium red wines discounted by up to 77 per cent, priced from $550 a bottle. Like all offers which seem to be too good to be true, I sought the reasons from a wine insider.

Yes, when I read the name of the wines out, they were individually fine wines. He further said that he tended not to accept the rating system, where 100 was perfection and hardly ever reached. He relied on his taste buds, the distillation of multiple cranial nerve connections with the mouth, including the complex innovation of the tongue. However, the ratings were there to reassure the potential purchaser.

The prices stated in the AMA advertisement were those projected for the overseas market. Unfortunately, when the tariffs were removed by the Chinese Government, the expected surge in the Chinese wine trade has not eventuated. The Chinese are not buying Australian wine; they have gone elsewhere during the time Australia was punished with high tariffs.

Added to that, wine consumption all over the World is falling, and this applies particularly to red wines – at a time when there is a glut of wines worldwide.

I note that ABC’s Landline ran a segment on the sale of Australian wines to India. The tone was optimistic, but I’m sceptical. Only a small percentage of Indians drink foreign wine behind a high tariff wall (150 per cent). Having ordered foreign wines and spirits in the various hotels in which I have stayed, you would think that Ned Kelly was an Indian, so great was the cost.

Alcohol cannot be advertised in India, which inhibits the adoption of wine, and even given the growing Indian middle class together with a growing number of Indians now living in Australia who retain family contacts on the subcontinent and can be used as a positive factor for an increase of wine’s popularity growth remains slow. One source warned nevertheless: “The majority of consumers are more focused on wine’s pricing and taste; since it is not an indigenous beverage, consumers often have only a basic understanding of the right etiquette to purchase, order, serve, or drink wine, nor do they know about wine regions and varieties in detail.”

Personally, I would never drink wine with a curry. Beer is the preferred drink if you need alcohol to wash down the vindaloo.

Completely Irrelevant as any Sporting record

One of the idiosyncrasies is how guys like Gideon Haigh and Bruce McAvaney have turned their encyclopaedic memory for sporting trivia into a career. Both have a dedicated following, as though retention of irrelevance confers some oracular status. For most of the community such modern Data Oracles are just dead boring, but then I would have found the Delphic Oracles not to my refined philistine attitudes – emoting rubbish to a rapt audience.

So, as with any good hypocrite, I have joined in to discuss the rise of a German football team, Bayer Leverkusen. The team was founded in 1904 by employees of the pharmaceutical company, Bayer. The company headquarters are in Leverkusen in North Rhine – Westphalia. Traditionally it has been an also-run team.

As The Boston Globe stated “Bayer Leverkusen are standing on the precipice of history” – whatever that means.

The narrative explained that this lowly German soccer team has just finished its Bundesliga season undefeated (51 wins), the first team to achieve the feat. Teams in other leagues may have gone undefeated, but none has ever done what Leverkusen had done in the Bundesliga. The ballon burst with the first of their final cup challenges. Leverkusen lost to Italian club Atalanta in the Europa League final 3-1. Leverkusen rehabilitated themselves by then winning DFB Pokal Final (German Cup) against the Rhineland-Palatinate club, FC Kaiserslautern 1-0 last Saturday.

Why the success? Hiring a smart guy with a chequebook.

Early last season, with the club in second-to-last place, they hired Xabi Alonso, a Spanish former midfielder with a very good coaching record. He made some shrewd signings, and voilà…

Leverkusen started well, salvaged six tied games and did not relinquish first place after the sixth week of the season. Must thank Gabe Edelman for this piece of priceless sporting trivia which obviously eluded my companion sporting bores. Who’s interested in German football in this Country when there are irresistible data about the number of runs made by JMux or the number of jockey premierships been won by David Wornout. Or did I get that wrong?

Mouse Whisper

One of the obscure topics the Boss was talking about was the Livery Companies of various trades set up in London from mediaeval England onwards when the trades began to band together as de facto Unions without the cloth cap association. The first were the mercers, from which the generic name of “Merchants” is derived. They were essentially traders in cloth, unsurprising given the importance of the wool trade to England at that time.

One matter which led to the phase of “being at sixes and sevens” came about because of the dispute about which Worshipful Company, Merchant Taylors or Skinners (furriers), should be ranked six or seven, a dispute over which received its charter first.

I’m indebted to Wikipedia for the following. In 1515, the Court of Aldermen of the City of London settled the order of for the 48 livery companies then in existence, based on those companies’ contemporary economic or political power. The 12 highest-ranked companies remain known as the Great Twelve City Livery Companies. Presently, there are 111 City livery companies, all post-1515 companies being ranked by seniority of creation, the last, number 111, being for nurses.

I was pleased to see there is not a Worshipful Company of Mousecatchers.