We both have had an injection of the vaccine against the Virus this past week. My wife received the AstraZeneca (AZ) vaccine, having been slotted in because of a vaccination cancellation in the general practice, her earlier booking having been cancelled when vaccines were diverted to Melbourne during its last outbreak.

Because of my complicated medical history, I was placed in the bureaucratic imbroglio of being allowed by government to seek a recommendation from my doctor to receive the Pfizer vaccine. You know, the new definition of infinity.

The problem is there is not enough Pfizer vaccine in this country at present, but there is another problem in the supply chain. While in one area there is a clamour to have the vaccine where the freezing facility is bare; in others there is vaccine to spare; needing an arm in which to inject. So, it is a game of chance when distribution is a mess. Serendipity kicks in, and I was fortunate.

There is this disconnect between what the politicians announce what happens on the round. RPAH for example, was swamped by people under 50 wanting Pfizer vaccine. RPAH and ST V’s are just not mass centres. Their level of communication is minimal or non-existent, as they refine and then refine again the definition of infinity. It is the place where two bureaucratic streams playing in parallel meet.

There is this disconnect between what the politicians announce what happens on the round. RPAH for example, was swamped by people under 50 wanting Pfizer vaccine. RPAH and ST V’s are just not mass centres. Their level of communication is minimal or non-existent, as they refine and then refine again the definition of infinity. It is the place where two bureaucratic streams playing in parallel meet.

Yet the professionals on the ground are very good, given the tedium that any mass action, whether it is testing or treating, with long hours – their remuneration is not questioned, but the same task.

For those tossers in marketing, the injection is not a jab. They should know it’s a small prick in the arm without residual pain or tenderness. Morbidity after the first injection of AZ is reasonably common and anecdotally the severity varies from a day or two of “unwellness” to a need for hospitalisation. This is unrelated to the much-hyped problem with clotting. I suppose the reaction should take comfort in knowing that this shows the vaccine is working.

Still, I was lucky to be able to receive a Pfizer vaccination. Having unsuccessfully contacted multiple sites to try to get a vaccination, and having received no assistance from the Government sites, I managed to get a vaccination when there was one unused from a vial and because I could get to the location quickly.

I was told as I filled in the Pfizer form that the second dose, unlike the AZ vaccine, is more likely to provoke side effects. The paperwork is detailed, and one question I was asked would have most people scratching their heads. It enquired about mast cell disease. I would imagine most people do not have a clue about mast cells. They are important tissue cells involved in the first line defence against inflammation and infection. They contain both heparin and histamine and stain blue (basophilic), but mast cell diseases are rare, although often severe when it occurs. Maybe those with the disease know when they are asked the question.

But why ask it in this questionnaire? Apparently in people with mastocytosis, Pfizer vaccine can trigger an anaphylactic reaction. Somehow, unlike the AZ furore, it has escaped the eye of the experts or media. Nevertheless, on a slow news day…

There is one very deep problem in the messaging. To try and shift responsibility, the politicians and the bureaucrats say if you are troubled by the prospect of the vaccine side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist; when English is not your first language, that message invariably will cause confusion. The confusion also arises because of the messages to stay home, isolate and get tested – conflicting instructions.

Some interpret the message as when they feel sick they should go to the doctor not to the testing centre. Hence, the infected have been turning up at doctors’ rooms or at pharmacies, and potentially compromising primary health care. Fortunately, it seems to be limited, but the more the message remains ambiguous, the more likely the infected will turn up in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In relation to pharmacies giving the injection, the average pharmacy is constructed as a retail outlet not as a health centre. Many pharmacies are configured with narrow aisles crammed with all sort of goods. Is that the place for an injection of vaccine where there is a long form to be completed, concerns to be allayed and the need to wait 15 minutes after in case of a reaction? Even though pharmacists are used to managing cold chains, more so than most doctors, is the configuration appropriate? Yet I would ask the question of whether you would be injected in a shoe store? Well, very unfair, you say. But then I do remember when some pharmacies sold cigarettes.

Yes, an example of the relevant pharmacy standard abridged shorn of some of the prolixity, indicates: “The vaccination service must (a) have sufficient floor area to accommodate the person receiving the vaccination and an accompanying person, and the pharmacist adequate space (b) have sufficient a bench space with an impervious surface, a chair and a first aid couch (or similar)(c) not permit the vaccination to be visible or audible to other persons in the pharmacy. …There must be at least 4 square metres to ensure that if required in an emergency, a patient could lie down on the ground (sic). Additionally, that there must be a dedicated area to enable the vaccination service to be provided.”

Who is to check compliance and can anybody show me where the model based on this standard is in operation?

As a footnote, I started writing this blog while Berejiklian was talking at one of her media conferences. Her first default position is to talk about herself, basically the why-are-you-so-unkind routine. “I have not seen my parent for a month.”

The second is to act as Pollyanna, which leads to mixed messages. For instance, when asked about whether people can go to the shop over the road when over the road is over the local government border, did our Gladys say “No”? Instead, she fluffed again, saying people should use their common sense and thus effectively countermanding the government order. She should understand by now that common sense is not necessarily a common commodity in the community.

Her indecision was shown so starkly in relief when the Victorian Premier and his officers fronted the media soon afterwards. There was information More concisely given; the messaging clearer, but she still talks too much – the sign of guilt of the child trying to talk her way out to avoid punishment.

She has found a new word “quash”! Ask 100 people in the street and see how many understand that word, particularly in the critical areas of SW Sydney. Each of these are trivial criticisms but there is a compounding effect.

Several days later, she did realise that fluff and Pollyanna did not work, as she seemed to try to change her persona to the Iron Woman from Willoughby. She still talks too much.

What will be her next role in front of the media while some of the community watch on?

One for the Armenians

A crush of new cases fuelled by the fast-spreading delta variant has threatened to overwhelm Iranian hospitals with breathless patients too numerous to handle. But as deaths mount, and the sense swells that protection for most citizens remains far-off, thousands of desperate Iranians are taking matters into their own hands: They’re flocking to neighbouring Armenia.

In the ex-Soviet Caucasus nation, where vaccine uptake has remained sluggish amid widespread vaccine hesitancy, authorities have been doling out free doses to foreign visitors — a boon for Iranians afraid for their lives and sick of waiting.

Gladys’ relatives are showing a humanitarian streak in Yerevan towards their neighbours. The Iranians have the highest COVID-19 infection rate in that area, yet only two per cent are vaccinated. The Armenians show their merchant finesse, having obtained Pfizer and AstraZeneca plus the Chinese and Russian versions, all for their 3 million population.

Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus Augustus

When I studied Roman History, to me the best time to be around in Rome would have been in the second century A.D. (we did not use BCE). When I was a youngster, I always wondered why and how, despite all the debauchery and hedonism mixed with sadistic brutality, did Rome survive the first century after the death of Augustus.

However, from Trajan to Marcus Aurelius, it seemed to be so that Rome entered a “moral period”, with these two emperors being bookends between Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. This was the Golden age.

Hadrian and Trajan were related, being distant cousins. Trajan is always viewed as the conquering hero, who extended the Roman empire to its widest limits. Only after I visited Romania did I comprehend the difficulty of subduing a countryside wedged between the Carpathian Mountains and the Danube. The Danube is two-edged by forming a barrier between Roman troops and the Germanic tribes. It kept the latter out. Once the Romans bridged the river they had lost a bulwark. Their time in Dacia as it was then called (now modern Romania and Moldova) lasted 150 years. Even though the Romans were there briefly, the Roman legacy is the Romanian language.

My youthful romantic notion then was of Trajan the conqueror, a man steeled in the playing fields of Rome. Hadrian was the studious builder who came along and built walls, preserved heritage. Given the way history was taught in deference to our British heritage of the time, Hadrian was primarily a wall in the North of England.

Hadrian’s Wall stretched across the northern English countryside, south of the modern border between Scotland and Wales. All walls which stretch across countryside attract visitors, especially if they last 2,000 years.

Eighty Roman miles long (117 kms), it crossed northern Britain from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west.

Most of it has gone now, but as we found out, meandering along beside it (once you could walk on it), this remaining wall is impressive as it indents, curves and disappears over the distant hill. In parts the wall is quite low and you can peer over the top, looking down on the undulating greenery folding into the dales. It is unnervingly peaceful now, thinking of the Roman defenders in combat against blue painted warriors, their Pictish accents incomprehensible yowling, rushing up the slopes with spears and shields.

I still have a copy of the source material, Cary’s History of Rome. It is a very dry account, packed with facts, but steers well away from Hadrian, the person.

It is said that the Memoirs of Hadrian, a fictional epistle from Hadrian in old age to Marcus Aurelius as a youth is one of the “imperishable” biographies of the 20th century. Written by Marguerite Youcenar in 1951, it was translated from the French somewhat later, and of course was not in the curricular diet of an impressionable youth such as myself.

I was to find out later that Hadrian was homosexual, a word in my schooldays larded with a snigger of derogatory epithets. Certainly there is nothing about this in Cary nor about Hadrian’s young Greek lover Antinous, who died tragically on the Nile. He was the subject of many extravagant memento mori by the grieving Emperor.

As has been written, Roman emperors seem to be divided between monsters and mediocrities, with an occasional near-genius, like Hadrian, thrown in to break the monotony. Highly intelligent and cultivated, he was a Grecophile, always a good sign in the ancient world. As emperor, he attempted to pull back from the imperialist expansion of his predecessor Trajan and wanted, as the chronicler Aelius Spartianus put it, to “administer the republic [so that] it would know that the state belonged to the people and was not his property.”

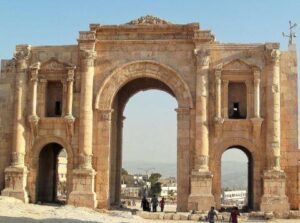

There are many monuments scattered around the Roman lands. At the northern entrance to the ruins of the Roman city of Gerasa, on the outskirts of the modern Jordan city of Jerash, there is the huge Arch of Hadrian, an entrance through which only the privileged could walk into the city. Gerasa was destroyed in an earthquake in the eighth century and was buried under sand for a thousand years, which meant that when it was uncovered, the ancient city was in reasonable condition, including the Arch.

Walking around the ruins of the city, the Arch of Hadrian, built in 130 AD, stands out. It is as though it is a symbol of an emperor, who was not the conventional cardboard character of a Roman emperor but that very complex character, who knew he had to consolidate his cousin’s expansionary strategy. After all, Dacia was not just expansion for the sake of expansion. The mines there were the source of gold and silver. It was one of the tasks that Hadrian had to balance to maintain a profitable empire, rather than continuing conquest being an exercise in hubris.

Oh, and by the way, Hadrian’s wall was built starting in 122 AD, five years after he became Emperor at the age of 41. I doubt if it was a modest expectation.

Americanus Imperator

On both 11 September 2001 and 7 December 1941, the most powerful country in the world was ambushed. There is a word which has crept into the language “proportionate”. In the case of the Pearl Harbour attack, it was clear that this was a pre-emptive strike by the Japanese Imperial forces, the responsibility for the attack extending to the Emperor. The American revenge took four years, but bloodied and scarred, with 405,399 deaths, (comparable with deaths from the American Civil War) America emerged victorious; and so the myth of American invincibility was born.

Grateful for survival, Australia since then has followed America into the Korean War, admittedly fought under the United Nations banner, then almost a decade in Vietnam, and then 20 years in Afghanistan after a gap of 26 years. The results:

- Korea – a festering stalemate at a cost of 36,000 American lives;

- Vietnam – now a united country on the cusp of prosperity – a defeat in 1975 for America at a cost of 58,220 American lives; more than three million mines remain as the American legacy, with 40,000 Vietnamese killed or maimed since;

- Afghanistan, 20 years – Taliban about to resume transmission, a defeat for America at a cost about 2,400 American lives (about the same number as the War of 1812 when the Americans were battling the British).

The following recent American assessment is unsurprising:

After having invested so much for so long in Afghanistan, we cannot now escape responsibility for its fate. In 1975, a U.S. Army colonel famously told a North Vietnamese colonel, “You know, you never beat us on the battlefield.” His counterpart responded, “That may be so, but it is also irrelevant.”

Indeed, guerrillas prevail not by outfighting but by outlasting a more powerful foe. The Taliban has done just that. It has not yet defeated the government in Kabul, but it has already defeated the one in Washington. Let the recriminations and finger-pointing begin. If Vietnam is any indication, the Afghanistan “blame game” could roil U.S. politics for decades to come.

The revenge for 11 September had thus been blown up. Anyway, 15 0f 19 conspirators were Saudis, and the Saudi royal family were allowed out of the country with the blessing of the Americans at about the time of the attack. Revenge needs a target, and a target was confected and 20 years later the Americans are farewelling the battleground of the Hindu Kush, defeated.

I would not bet on when the next exercise will occur. After all, there is always a need to use all these bright and shiny new weapons. Interesting to see the latest war exercise in Australia (take note) concentrating on a sea-land attack. Reminiscent of a World War scenario, but how relevant to modern circumstances? War games have a periodicity, and as long as advances in technology are subverted for such activities there will always be more wars, with the armed forces increasingly bearing less of the pain, it being transferred more and more to the civilian population caught up in each particular war game. I only hope that Australia does not get a home game.

Japan – In Search of a Hill

Alan Talbot is a remarkable fellow, remembered as a self-assured Pommy kid who descended on my school. I didn’t know him well at school, but I recently caught up with him. He had a life as an accountant; mine was in medicine. I found out that he and a school friend, just after the last term of school, went walkabout in northern Queensland, with little if any money, quickly aborted.

From a young age Alan was a venturer, on show when he was at school in England where he rambled across the Lake District, and scaled Scafell Pike, in a very busy and varied trip. He has written about this and Mt Fuji in a book published last year called In Search of the Hills.

It took many years before he struck out on his mountain adventures as an adult. One of these was taking a break from a conference in Japan when he decided to climb up Mount Fuji despite it being October. The mountain was closed to tourists, with ice and snow on the climb. Alan was warmly dressed but hardly in serious mountain gear. When he reached the point about halfway up where the road ended, he noted the signs said “closed”. Nevertheless, he noticed a Japanese guy exercising beyond the border – running up and down. He, as Alan tells it, was only running up and down 50metres or so; but that was sufficient encouragement for Alan to follow him over the border.

Fortunately, he had started early, and the mountain just encouraged him upwards. Once started, the mountain beckoned him to the next outcrop; to the next patch of scree. On the way he found a discarded parka, which although too small, gave him some protection for the climb to the summit. Once, he reached the summit, he walked around the rim, which was about a kilometre, meeting a troop of mountain climbers, who had climbed up the tougher approach but with a permit. They were shocked to see this person in little more than warm clothes.

Even if they may have disapproved what could they do with somebody who was loping along with the exhilaration of being at 13,000 feet (3,620 metres). It took him six hours to go up the mountain, where he spent one hour and then three hours to go down the way he had come. He, blackened with scree, emerged into the carpark to the astonishment of tourists who had come to see the base of the mountain in the fading light which provided a perfect vista for him as he climbed down the mountain.

Alan just did it, without any fuss.

So different from our experience when we decided to follow the instructions in a Michelin guide to go to Mount Fuji and learnt that what appears as a few lines in a book is in fact not just a matter of changing trains seamlessly and ending up with a picture book view of Mount Fuji.

We had gone to Tokyo at Easter. It happened to be cherry blossom time, just over its peak, but still providing a delicate panorama of white and pink blossoms.

We stayed in the Imperial Hotel, but the reason for doing so is another story. We were lucky to have a room in this hotel because it is always full at cherry blossom time.

Japonisme had its genesis in this and other portrayal of Japanese flora. Cherry blossom in full bloom is a magnificent spectacle because there is something in the delicate colour and the nature of the blooms which exemplifies that beauty is so fragile. As the blossom is buffeted by nature, it quickly loses that bloom of youth – once robust in its white and pink announcement that a new life has arrived. Then the petals fall and accumulate as white and pink detritus on the pavement. The blossom clings, a thin remnant, until eventually it is gone.

However, if cherry blossom defines Japan, then so does Mount Fuji. If you travel by bullet train to Kyoto and you are on the right side of the train you see it briefly arising amid a landscape of poles and wire, industrial drabness and clustered houses which were defined by Pete Seeger’s song, increasingly long ago.

We decided that we wanted to see Mount Fuji close up and we had this Michelin recommended route. The hotel concierge was polite and suggested mildly that the recommended way was complicated. “Understatement” is a Japanese characteristic rather than saying why do it.

The result was a confusion of trains. We had Green Passes equivalent to first class (the very fast Nozomi bullet train was excluded). So the train out of Tokyo on the Kyoto line was comfortable enough, fast enough, excellent by Australian standards

We had to change at Kawaguchiko where we transferred to a private railway which zigzagged its way through the gorges, past picturesque Japanese villages to Gora, where the cherry blossoms were still a filigree. It was slow and rickety, and by the time we got to there we had yet to see Mount Fuji. Then we had to board a funicular and then cable car railways as we wended higher up the mountainside and then down to Lake Ashinoka. We strained to see Mount Fuji as we rose and fell on the mountains and then on the colourful lake ferry. Surely we would see the mountain now, but no, it was blanketed in mist.

The problem was when we arrived at the other side of the lake, where normally a bus would take us back to the railway station to board the Tokyo train, there was a huge queue of people and no buses – well very few with an officious little man determining who was given a seat. This was the problem in Japan when matters go wrong, and there is nobody to speak English; with signs comprehensible only to the Japanese. There are no concession to the visitor.

Sunset had come and gone. Everybody was concentrated on getting out of the cold and into a bus. A sprinkling of taxis arrived and at last after two hours one was within reach. We piled in unceremoniously, me waving my stick to indicate both determination and disability. Two young Guatemalans joined us, crammed into the back seat; and off we went into the night. At last we arrived at the railway station. Tokyo thankfully was now within reach. The station was surprisingly sparsely populated, considering the melee we had left. One Nozomi rushed past without stopping, but eventually a train did stop.

The concierge had been right. The route we had taken had successfully blended “tortuous” and “tortured” into an unforgettable day. Symbolic of this had been that part of the journey above the Owaki-dani, the valley from hell, where the steam bubbled through the cracks in the volcanic landscape, the air was pungent with sulphurous gases, Lucifer not far away.

We had not seen Mount Fuji, but we knew more about the train lines of Japan. In fact we were to use the Green Pass only five time traversing Honshu. I wished we had had Alan Talbot with us; he would have destroyed any barriers.

Mouse Whisper

Queixo ou Queijo

Now make sure you don’t get your chin in your cheese

When you are dining with the Portuguese.