Before the age of blogs I used to listen to Alistair Cooke’s Letter from America, in which he would take a current situation and tie it into past lessons learnt, and in such a way that each letter was a beautifully crafted piece of writing with a beginning and an ending – a complete expression of his view, with a moral woven into it. An Englishman, he had gone to America before War II and became a US citizen in 1941. He not only had this gift as a writer but also as a TV and documentary producer and presenter. His insight into the American way of life was his core expertise, and he wrote it. His voice, with its perfect diction and ghostly tone with a slight tremolo, was particularly engaging, because of his distillation of intimacy. He may have been broadcasting to the world, but as you listened you felt he was speaking directly to you.

I would have liked his life as an intellectual commentator but writing a “Blog from America” for 58 years … I wonder. As for emulating his TV career – no. I would have been hopeless. The smell of the greasepaint and the roar of the crowd makes me throw up, so phobic I am of the TV studio.

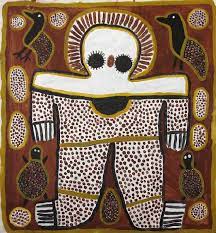

Forty years plus ago I went to the Kimberley and wrote several short stories centred on the places I visited. The story reprinted below entitled “The Island” recounted most closely my experience, while stretching reality into a yarn. It was the first time I felt the unspoken force of this country, without being privileged to have Aboriginal heritage. I have divided this story into several parts, and the first part introduces the Wandjina.

As background to the story, I searched throughout the various places I visited in the Kimberley looking for a bark Wandjina. Apart from a few images in books, I knew very little until I saw images of Wandjina on rock walls.

I managed to find one small bark Wandjina for sale in Kununurra, which I gave to my elder son. Since then, my wife and I have acquired several Wandjina painted by the Karedada sisters – Lily and Rosie (the Karedadas were the family with the responsibility at that time for painting Wandjina); a small bark painting by Waigan and one where the provenance was unknown as it was created in the mid-1960s when such bark representations of the Wandjina were new. Most of these bark images came from the Aboriginal people living at Kalumburu, a settlement on Mission Bay about 230 kilometres north of the Gibb River Road turnoff in Western Australia. Here the Spanish Benedictines had established a mission in the early part of the twentieth century. One of my teachers had said that during WWII, when he was in the Australian navy, he had been stranded there. The priests only spoke Spanish and he not; therefore, they communicated in Latin. No mention in any of his anecdotes of contact with the Indigenous people; such were the times.

I managed to find one small bark Wandjina for sale in Kununurra, which I gave to my elder son. Since then, my wife and I have acquired several Wandjina painted by the Karedada sisters – Lily and Rosie (the Karedadas were the family with the responsibility at that time for painting Wandjina); a small bark painting by Waigan and one where the provenance was unknown as it was created in the mid-1960s when such bark representations of the Wandjina were new. Most of these bark images came from the Aboriginal people living at Kalumburu, a settlement on Mission Bay about 230 kilometres north of the Gibb River Road turnoff in Western Australia. Here the Spanish Benedictines had established a mission in the early part of the twentieth century. One of my teachers had said that during WWII, when he was in the Australian navy, he had been stranded there. The priests only spoke Spanish and he not; therefore, they communicated in Latin. No mention in any of his anecdotes of contact with the Indigenous people; such were the times.

Anyway, here is the first part of the story; the eyes are those of my hero, Bill:

In the Northwest of Western Australia in the winter of 1979, the sun starts to set before 5 o’clock. In fact, in that season, it sets at the same time every year. It’s a big country, Western Australia. Bigger than Texas. And the clocks are set to Perth time, even when one is far from the comfort of having a second martini and enjoying the broad sweep of the Swan River. The clocks of suburbia determine that the sun sets prematurely in the north country where the gulfs in the dreamtime were torn out of the coastline and waterfalls run horizontal. Sixty kilometres up one of these gulfs lies the Port. The expanse of water it overlooks is called the Gut. It vaguely resembles a flaccid stomach. In the pale purple twilight, the hills brood over this tiny town with its shacks distinct from the new fibro-cement houses on the other side of the hill. Bill surveyed the car in the fast falling light. Parked on the rise outside the police compound, it had two flat tyres. The lady from Avis had said that he could have the car if he could get to the Port and pick it up. It was the only hire car available. She said it would be very recognisable because it was iridescent purple — just a medium-sized sedan. However, as he surveyed the car, he could see it had no protection — none of that ugly but highly effective steel tubing, the so-called roo bars, nor chicken wire to protect against stray rocks through the windscreen. And there were the two flat tyres. The Port began to twinkle with ship and house lights. The timber shop fronts threw pools of yellow light onto the street. But back to Bill. The highly qualified Bill. Bill, the centre of his own rather inconsiderable space, was a medical practitioner in his early thirties. His family was “old money”. He had mixed his profession with research. His days were spent closeted in a laboratory, occasionally venturing into the antiseptic stretch of the ward to teach a few students and to pronounce on the inmates’ futures, for a price. Bill had reached a steady kind of existence, punctuated by dinner parties, the game of squash, the odd casual affair, and cultivated displays of intellect at conferences, seminars and workshops. Holidays were spent in expensive resorts. That is to say, generally. This year, Bill had decided to come north and have an adventure of sorts. Bill was accustomed to pre-booked travel, accommodation with deferential staff and a car readily available, with a driver if necessary. When he had flown into the Town on the Dam, he expected the same, even though his arrangements had been made in a hurry. “No way!” she had said. Cars were at a premium. You can try other hire car outfits, but you’ll get the same answer. She had paused. There was one option. “The only car is up the Port, and if you can get up there, it’s yours.” She paused again and then went on. “It’s got two flat tyres you’ll have to get fixed.” No wonder it was stuck there, he thought. Didn’t know whether he could do it — make the Port. But when he got back to the motel, he noticed a group preparing to leave. He recognised one as a prominent ear nose and throat specialist from Perth. The specialist was heading a team charged with doing good. He wondered where they were going. He asked. They were going to the Port. He was offered a lift, and straight away accepted. These guys knew the north — they had spent the latter part of their professional lives coming back and forth at least twice a year to treat the local Aboriginal people and the whites alike. Ear infections were rife among the Aboriginal kids — needed grommets in many cases. They were good blokes, with a sense of enjoyment of the Land. They had an easy familiarity with the sweeping majesty of the country, where the Cloud spirit was still in control and white people only visited. She had bestowed her grace on the black people, which reflected from the deep pools in their eyes. Look into their eyes and see the arcane. It was Aboriginal country. They walked free in the country without compass. They defined their ownership and boundaries. Bill listened to this explanation. Maybe it was a white man’s interpretation. Bill had sat next to the specialist surgeon who was leading the team, and who had provided his view of what he called “the blackfella”. It was all so unfamiliar to Bill. He had hopped from town to town, seeing the sights, seeing the Aboriginal people roaming the streets, but he had no experience of communicating with them. Their driver was identified as a Ngarinyin man who knew the country. They called him Stanley. He was a broad chested man with an equally broad smile. He wanted to know whether Bill wanted to see some rock paintings on the way. The leading specialist thought it a good idea, that it would give Bill an experience — probably “teach you something.” “Sure” said Bill. The sun was pleasant. It was June. The company was convivial. Even when they stopped and walked, it was exhilarating. There had first been a track which could be negotiated for some way with the four-wheel drive, but in the end it was easier to walk through the deep sands of the dry creek beds. This was Stanley’s country. The guide shaded his eyes and indicated the rock face. The brown cliffs where the paintings were, he’d explained as they’d walked, were thankfully not well known and the track, although not particularly difficult to walk, was sufficiently far from the main road to deter any casual defiler. There was always some idiot wanting to scratch his name on the wall — any wall. Weaving in among the woollybutt eucalypts, the track moved up and then downwards. As they walked, the day was imperceptibly vanishing. The shadows were lengthening as they picked their way along the rock face where the figures were displayed. There were large fish — here a snake — there a hand, an impression in red ochre dust. Tasselled dancing figures. He was told they were called Bradshaw figures, and there were doubts about their authenticity. They were not Aboriginal figures, unlike the wandjina. He had never seen them before. The wandjina were cloud spirits — images with eyes and speckled brows. Their heads were surrounded by radiating lines, which completed an aura. This wandjina was a wellspring of sacred images for the Aboriginal people, unlike the Bradshaw figures. Some of the paintings were high on the cliff walls; some under overhanging ledges. The gallery ran for hundreds of metres around the cliff until it reached the point where a waterfall flowed in the wet season. The artists had stopped here; the mural was complete. The rock pigeons, their fusty brown feathers giving a sense of an age past, were coming in to roost as the day began to wane. “Better get going. Still got a way to go.” The voice broke the stillness, as they had said little, as if in church. The others had seen it before; they had pointed out features in quiet, clipped tones. Bill had nodded and absorbed as much as he could. He wondered at how irrelevant had been his experience in Downtown Perth on a Sunday afternoon, sipping the art gallery ambience. He had really not particularly liked Aboriginal art — bark painting. There was not much of it that he could remember anyway. But here, in a brief moment, he had got some sense of the art, some context for it — a fleeting insight only; not the meaning that Stanley possessed. (to be continued).

Door County

Door County is a spit of land separating Lake Michigan and Green Bay in northern Wisconsin. Green Bay, the city, lies at the gateway to the peninsula, and has been settled since the seventeenth century when it was a base for fur traders. It is now known for paper manufacture, of being the toilet paper capital of the world – and the home of the NFL Green Bay Packers, so called because a meat packing company gave them $500 for uniforms when they were founded.

Anyway, we bypassed the city of Green Bay, which gets its name from the periodic algae infestation of the Bay. Yet Door County, once you clear the environs of Green Bay, is one the memorable places we have visited.

Memory of that time was bought on this week by the news of a three generation Ukrainian heritage family that has been mass producing candles in the Ukrainian colours (sale proceeds going to the Ukrainian cause) which, unsurprisingly once this was published on national television, elicited a strong demand for the candles across America.

It was Halloween when we visited Door County; pumpkins were everywhere, and the normal crop of witches, faux cobwebs and skeletons and things that are supposed to go bump in the night was very much in evidence.

We stayed in the traditional white clapboard Ephraim Inn, overlooking Lake Michigan. When we went to dinner, we had an unexpected shock. I asked for the wine list and was informed that Ephraim was “dry”. If we wanted a drink with our meals we would have to go down the road to Fish Creek. Fortunately, Fish Creek was well served by restaurants and the Coho salmon fished from the Lake was so good it enticed us to order it two nights in a row.

Since our visit, I believe that Ephraim has lifted the 163 year old ban on alcohol sales which was imposed in 1853 within this Moravian community, where its church with its delicate steeple still stands on a green knoll overlooking Ephraim.

It was the end of the apple picking season, and there was an abundance of places from which to buy apples. The Gala apple was a familiar variety, but there were at least 20 other varieties and we chose the Honeycrisp, a hybrid noted for its juiciness and crunchiness. But there were many more completely unfamiliar to our Australian palate such as Ginger Gold and Courtland.

We drove the length of the peninsula through the small seaside towns, beside orchards, around windy cliff roads. To me, village America always has its gentle attraction – so different from the dusty flood plain called Australia. As for Door County, even though it seemed to be an endless excuse for Bing Crosby or Doris Day songs, we said we would be back, but we have said that about many places – plans that the Virus has impaired if not totally destroyed.

Anyway, we must get a candle making kit.

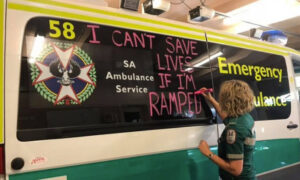

Need to Ramp Up

In The Monthly two months ago, Russell Marks wrote a very prescient article about South Australia opening its borders at the time the Omicron virus hit and now has followed the B.a.2 variant.

Simply stated, the Premier, Stephen Marshall, opened the SA borders prematurely – at a time when the Omicron variant first appeared on the scene. The SA Chief Health Officer hurriedly changed her mind when she saw the rapid increase in the number of cases, and recommended the borders be closed again. The Premier did not take her advice. He deferred to the select audience of the Rupert Murdoch and Peter Costello media and its impatience with public health measures.

It was the people of South Australia who could see what damage the Virus was wreaking. This was particularly reflected in the disruption to the health services, and the so-called ramping. In other words, there was the number of ambulances lying idle unable to discharge the patient into the hospital’s emergency department.

I have reviewed extensively two major ambulance services in Australia and have a fair idea of the problems, which extend far wider than the problems that a pandemic introduces. The pandemic has only emphasised these problems.

Against that background of a State under public health stress, the Premier said that he would prefer funding a basketball stadium and a convention centre which only compounds the politico-pathological requirement to build monuments. Once it was hospitals and universities, now it is modern day colosseums where the pork barrel stops.

Despite the media in his favour, Marshall was soundly defeated; and yet elements of the media still say it doesn’t necessarily translate into a Federal electoral defeat for Morrison, despite him being invisible during the campaign. The sight of John Howard being rolled out in the last days showed how far the Liberals were tapping the bottom of desperation. One question – never to be answered – would a Morrison intervention counterpointed by Dutton and Frydenberg, a modern magi, have helped? The locals thought not, but presumably when they do turn up during the Federal election the public will be able to have a direct say in how much it likes the frankincense.

What will be more interesting is how the new Premier will approach the Virus.

I am confused by what the current approach to the Virus is. It seems that the Governments have given up – the public health response is exhausted. Who are the public health champions? The public health talking heads have subsided with the media’s apparent loss of interest. One of public health’s weaknesses is how ineffectual the Australasian Faculty of Public Health Medicine has been and yet two decades ago it led the Australian campaign against French nuclear testing in the South Pacific until the French stopped their tests.

I would have thought that there would be a clear approach. On the one hand there are no restrictions, until a person gets the Virus and then you go into isolation until you test negative. Politicians are scared solid by lockdowns, and the core of preventative measures – social distancing, hand sanitiser and masks – are increasingly a matter of choice.

Vaccination has proved effective up to a point, but now there are no penalties for not being vaccinated, and the relentless anti-vaccination advocates leave a confused community. If this new variant is as contagious as measles, then without due precautions that will mean the whole community will contract it and for a substantial part of the community, the experience will not be a mild one.

The difference with measles is that once infected, once immunised, measles will not recur. No such guarantee exists for the Virus, even if the experts decide it is less virulent.

In public policy terms, I have been advocating dedicated quarantine centres. But once that line of defence is breached, then the next lines of defence are dedicated infectious diseases hospitals with an equally dedicated transport service for those who need hospitalisation.

Hardly the Little Match Girl

They buried Kimberley Kitching this week. A Senator from Victoria, she had been parachuted into the Senate under controversial circumstance in 2016 by Bill Shorten when he was ALP leader. She died prematurely at the age of 52, and from then, she became a cause célèbre – a woman harassed to death by unfeeling female colleagues.

As reported in some quarters, it was as though Senator Kitching was the “little match girl”, judging by the ferocious story being constructed around her demise. She was married to Andrew Landeryou, once joint owner of a palatial home “Wardlow” in Parkville; friend of Chloe Shorten since school days and embroiled in the Health Services Union known for its shenanigans while she was general manager.

Unlike the “little match girl”, Kitching came from a privileged Brisbane private school background. Her father was a university professor, and she benefited from a time in France to becomes fluent in French. She seemed to be a very quick-witted woman. Nevertheless, like many ambitious people she carved out a career never far from controversy.

In 2000, she married Andrew Landeryou, a scion of the inner ALP circle which his dad inhabited. He too has had his moments, from the time of his presidency of the Melbourne University Student Union (formerly, in my time, the Student Representative Council), where he apparently tried to commercialise aspects of that student body. It is strange that when I was President of the same body there were moves, ultimately squashed, to have the Council purchase property at Venus Bay, then an undeveloped collection of sand dunes. I remember looking at it and saying thanks, but no thanks. SRCs were not structured to be land developers. In any event, in his case it did not end well for young Landeryou.

Later he popped up in 2005, with a venture financed by Solomon Lew in part – and when it failed he decamped to Costa Rica leaving Kimberley, portrayed as the victim wife trying to deal with the remains. The suggestion was that Kimberley had been deserted, but whether that was so, they had been swiftly re-united even though Landeryou was bankrupted.

From December 2012, Kitching was employed by the Health Services Union and she was never far away from the controversy which surrounded the criminal behaviour of the local secretary of the union, the recently convicted Kathy Jackson, and the other national officers of the Union, also convicted. Whatever her role was, she obviously was close to some sordid shenanigans and her name was mentioned often in despatches.

For instance, in 2016, the Senate voted 35-21 to note that she, although its newest member, was found to have provided untruthful evidence to the Fair Work Commission. The Greens joined the Coalition in backing the motion, which also received support from three One Nation senators and Victorian senator Derryn Hinch. Quite an introduction!

The conservative Tasmanian Senator Abetz noted in a media release at the time, The fact that Opposition Leader Bill Shorten has backed Kitching so strongly in the face of findings against her from a body that Bill Shorten oversaw for two years, for conduct undertaken while he was the Minister responsible, that she was “untruthful and unreliable” in evidence speaks volumes about his personal and Labor’s standards for public office.”

Ironically, Kitching worked with him in the Senate to introduce a Magnitsky law that allows the government to seize assets from people who have abused human rights around the world.

This was no poor little waif as the media and a few of her mates are trying to portray now. She dined with persons who had clearly shown themselves to be enemies of the ALP, and thus one of the problems for a networker as aggressive as she apparently was, with all “the form” behind her, was whether she could be trusted.

To be able to do what Kitching, herself apparently conservative (in very much as I remember some of the Democratic Labor Party members were), was trying to do, is a particular art form, if one tries to balance on the barbed wire division of an adversarial political system.

Her colleagues who voted against the condemnation of her in 2016 were worried by her free-wheeling approach, whether right or wrong. She was not bullied; she was ostracised – however, the use of “bullying” is more emotive. Ostracism is a favourite ploy in politics.

She dies, and the conservative side of politics well known for their Salem approach to female opponents were on the job. The real target seems to be Penny Wong, as Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs, who has been a courteous brick wall. She made one exasperated comment which has been turned into a causal relationship with Kitching’s death despite occurring three years ago and eliciting an apology from her.

Morrison wants to run an election based on sabotage and camouflage and if Senator Wong can be discredited so much the better, especially given her appearance and name – nudge, nudge, wink, wink.

I suppose last Sunday’s ABC Insiders Program took the proverbial cake. I generally accept bias as part of politics, but this… Australia may be going to Hell in a handcart, but there they were, all over the Kitching case – at least Samantha Maiden and Spears Interruptus were.

Greg Sheridan played the avuncular role, his views laced within his long time association with Santamaria and the National Civic Council – a fading reminder of the strife within the Labor party, particularly in Victoria, generated by Santamaria and certain elements around Archbishop Mannix so many moons ago, but still apparently latent.

Mark Kenny, knowing he was in a setup, just let it flow apart from a few comments drowned out by the Interruptus. Australia is entering a time of a new form of Government – Murdocracy – a neologism to describe rule by the media.

Now, to the next phase – Albanese portrayed as the weak leader in the grip of three women – each of whom portrayed as having a doubtful allegiance to Australia. Yes, Murdocracy indeed.

As a postscript, I was interested in the association of sudden cardiac death and thyroid disease. Obviously I have had no access to Kitching’s clinical notes but it is worthy to note that in a 2016 cohort study in The Netherlands, an association was sought between thyroid disease and sudden cardiac death. This was an extensive population cohort and it was shown that raised levels of free thyroxine were associated with an increased incidence of sudden cardiac death, even when the patient was “apparently” euthyroid (in other words in the normal range).

It is well known that the thyroid hormone derived from the thyroid gland in the neck is a major component in the regulation of metabolism. For example, in thyrotoxicosis tachycardia is often present, as in hypothyroidism bradycardia is evident. However, The Netherlands’ paper could not establish any causal relationship for the phenomenon of sudden cardiac death, which incidentally also occurs in the autoimmune Hashimoto’s Disease. There was no mention of “bullying” or “ostracism” in this analysis

Mouse Whisper

In response to the article on banana boats last week our Swedish correspondent has informed us there is a job available in Stockholm for a banana ripener. The incumbent has recently retired after 33 years during which he has assisted the ripening of 55,000 bananas per year. Sounds a succulent job. I may apply. The Swedish text books with a tipple of Aquavit beckon.

As I probably mentioned in a previous blog, I accumulated New Scientist magazines, even though I never had time to read them. After I started writing the blog, as the magazines were conveniently stacked in the office, they served as a source of some of my material, even though some were 20 or more years old. Most of the issues came in an era before the modern technologies, and therefore there was a certain quaintness. Having fulfilled this purpose of providing source material, I broke the link which bound me in this state of habituation and threw them out.

As I probably mentioned in a previous blog, I accumulated New Scientist magazines, even though I never had time to read them. After I started writing the blog, as the magazines were conveniently stacked in the office, they served as a source of some of my material, even though some were 20 or more years old. Most of the issues came in an era before the modern technologies, and therefore there was a certain quaintness. Having fulfilled this purpose of providing source material, I broke the link which bound me in this state of habituation and threw them out.

Thinking through what Minister Hazzard had said, what would have happened if a State Health Minister had said during the polio pandemic – “It’s inevitable that everybody’s going to get it?” You could barely hear this Metaphor through the swishing of iron lungs and the clanking of braces attached to children’s limbs.

Thinking through what Minister Hazzard had said, what would have happened if a State Health Minister had said during the polio pandemic – “It’s inevitable that everybody’s going to get it?” You could barely hear this Metaphor through the swishing of iron lungs and the clanking of braces attached to children’s limbs.

The CDC also stressed that because some of the symptoms of both the flu, the coronavirus, and other respiratory illnesses are so similar, testing is required to “tell what the illness is and to confirm a diagnosis,” especially because people can be infected with both the flu and COVID-19 at the same time.

The CDC also stressed that because some of the symptoms of both the flu, the coronavirus, and other respiratory illnesses are so similar, testing is required to “tell what the illness is and to confirm a diagnosis,” especially because people can be infected with both the flu and COVID-19 at the same time.

“When do I want it?” The howl goes up. “Now.” The roaring response. Bugger the community or the Commonweal. The Eureka flag is limp.

A procession in front of Parliament House. Meanwhile Western Australia has declared neutrality. Then out of the winter sun comes a squadron of Zeros, that lay waste the protesters in the street. At least 40 members of the crowd were dead, strafed in the first run.

Fanciful. To make a point – or reinforce a point. Defence is a Commonwealth power. Once the Commonweal has been defined, then Defence is a Commonwealth responsibility. Before Federation, the States raised their own militia. For instance, the NSW Volunteer Contingent was raised to fight in the Sudan with the British Forces. Shortlived, the contingent of 700 men constituting infantry, artillery and ambulance went there and back with barely a scratch, although there are always casualties from exotic diseases.

“When do I want it?” The howl goes up. “Now.” The roaring response. Bugger the community or the Commonweal. The Eureka flag is limp.

A procession in front of Parliament House. Meanwhile Western Australia has declared neutrality. Then out of the winter sun comes a squadron of Zeros, that lay waste the protesters in the street. At least 40 members of the crowd were dead, strafed in the first run.

Fanciful. To make a point – or reinforce a point. Defence is a Commonwealth power. Once the Commonweal has been defined, then Defence is a Commonwealth responsibility. Before Federation, the States raised their own militia. For instance, the NSW Volunteer Contingent was raised to fight in the Sudan with the British Forces. Shortlived, the contingent of 700 men constituting infantry, artillery and ambulance went there and back with barely a scratch, although there are always casualties from exotic diseases.

So Omicron it was. But Omicron feels sketchy. How come no one had ever heard of it before? Maybe it’s one of those Clinton-Kamala Harris-Nancy Pelosi-Anthony Fauci-Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez-Lame Stream Media hoaxes.

So Omicron it was. But Omicron feels sketchy. How come no one had ever heard of it before? Maybe it’s one of those Clinton-Kamala Harris-Nancy Pelosi-Anthony Fauci-Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez-Lame Stream Media hoaxes. Black ice such as this is a “fairly rare” occurrence. Necessary conditions include the Greenland blockage, high pressure, rapid drop in temperature and no wind. The result is magic ice as though looking through glass and which provides extremely smooth skating. Our local mare is very reliable in providing solid ice but often not as smooth as this. Hopefully the incoming snowstorm will bypass us so that we can skate for some weeks to come (on the same magic ice).

Black ice such as this is a “fairly rare” occurrence. Necessary conditions include the Greenland blockage, high pressure, rapid drop in temperature and no wind. The result is magic ice as though looking through glass and which provides extremely smooth skating. Our local mare is very reliable in providing solid ice but often not as smooth as this. Hopefully the incoming snowstorm will bypass us so that we can skate for some weeks to come (on the same magic ice).

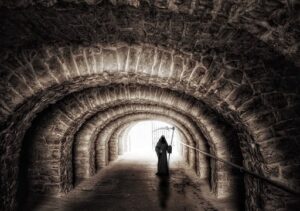

I did an online IQ test, finishing the 20 questions well within the allotted time. My score was 108. So, I am just average Giacomo, but I do have visual perception in the top one per cent. That’s great because I can perceive the light at the end of the tunnel as that hooded chap with a sickle waving a lantern. The problem is that I am not smart enough to calculate the length of the tunnel.

I did an online IQ test, finishing the 20 questions well within the allotted time. My score was 108. So, I am just average Giacomo, but I do have visual perception in the top one per cent. That’s great because I can perceive the light at the end of the tunnel as that hooded chap with a sickle waving a lantern. The problem is that I am not smart enough to calculate the length of the tunnel.

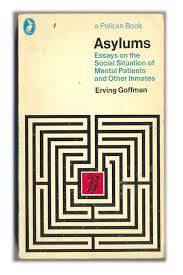

Does Goffman give any clue as to how the inmate should respond? No, he does not. His analysis of various responses to lockdown is well catalogued whether monastery or mental hospital. The concept of a prolonged imprisonment was not seen as the consequence when the Virus first appeared early last year. Then a selection of politicians from both sides of politics participated in light-hearted advertisements to encourage hand washing. It was as though it was similar to the mood at the outbreak of WW1 when the early prediction was of the conflict being over by Christmas 1914.

Does Goffman give any clue as to how the inmate should respond? No, he does not. His analysis of various responses to lockdown is well catalogued whether monastery or mental hospital. The concept of a prolonged imprisonment was not seen as the consequence when the Virus first appeared early last year. Then a selection of politicians from both sides of politics participated in light-hearted advertisements to encourage hand washing. It was as though it was similar to the mood at the outbreak of WW1 when the early prediction was of the conflict being over by Christmas 1914.

In recent years, in New South Wales we have seen: a Minister of the Crown gaoled for bribery; an inquiry into a second, and indeed a third, former Minister for alleged corruption; the former Chief Stipendiary Magistrate gaoled for perverting the course of justice; a former Commissioner of Police in the courts on a criminal charge; the former Deputy Commissioner of Police charged with bribery; a series of investigations and court cases involving judicial figures including a High Court Judge; and a disturbing number of dismissals, retirements and convictions of senior police officers for offences involving corrupt conduct… No government can maintain its claim to legitimacy while there remains the cloud of suspicion and doubt that has hung over government in New South Wales.

In recent years, in New South Wales we have seen: a Minister of the Crown gaoled for bribery; an inquiry into a second, and indeed a third, former Minister for alleged corruption; the former Chief Stipendiary Magistrate gaoled for perverting the course of justice; a former Commissioner of Police in the courts on a criminal charge; the former Deputy Commissioner of Police charged with bribery; a series of investigations and court cases involving judicial figures including a High Court Judge; and a disturbing number of dismissals, retirements and convictions of senior police officers for offences involving corrupt conduct… No government can maintain its claim to legitimacy while there remains the cloud of suspicion and doubt that has hung over government in New South Wales.

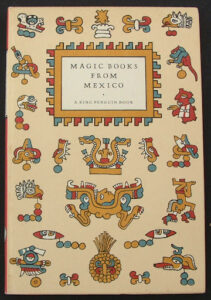

The first book had a pale green cover, with brown solid edges with white streaks between each brick, like ribbons of mortar. The full title British Birds on Lake, River and Stream lies over an inked cartoon of a kingfisher. There were 16 colour plates taken from John Gould’s massive collection of Birds of Great Britain, which extended to seven volumes. In a one shilling crown octavo pocket size book, the King Penguin is an elegant sampler, beautifully presented, of often esoteric subjects. The introductory description of this first one acknowledged how Gould spent several years in Australia and prepared a 600 plate Birds of Australia and is regarded as the Father of Australian ornithology.

The first book had a pale green cover, with brown solid edges with white streaks between each brick, like ribbons of mortar. The full title British Birds on Lake, River and Stream lies over an inked cartoon of a kingfisher. There were 16 colour plates taken from John Gould’s massive collection of Birds of Great Britain, which extended to seven volumes. In a one shilling crown octavo pocket size book, the King Penguin is an elegant sampler, beautifully presented, of often esoteric subjects. The introductory description of this first one acknowledged how Gould spent several years in Australia and prepared a 600 plate Birds of Australia and is regarded as the Father of Australian ornithology.

On the 9-10 May 2001, the House of Representatives met in Melbourne to celebrate the Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sittings. Twenty years on, only five of those who were sitting as Members that day are still members of Parliament.

On the 9-10 May 2001, the House of Representatives met in Melbourne to celebrate the Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sittings. Twenty years on, only five of those who were sitting as Members that day are still members of Parliament.

Richard Hatchett is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Oslo-based organisation formed in 2017. The following blurb, even suitably abridged, sets out the objectives:

Richard Hatchett is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Oslo-based organisation formed in 2017. The following blurb, even suitably abridged, sets out the objectives: Richard Hatchett in 2017 ended up running CEPI, which was a critical position as related in the book, because it was able to redirect substantial funding in the development of vaccines, particularly Moderna and AstroZeneca, when the pandemic struck and the Virus was isolated. Funding was also provided by CEPI to the University of Queensland for its ultimately failed vaccine. Considering the hype surrounding this group, perhaps more reliance was placed on its success than should have been. In any event, it left Australia with very few vaccine paddles, later in 2020. At that time Australia was basking in its success of suppression of the Virus.

Richard Hatchett in 2017 ended up running CEPI, which was a critical position as related in the book, because it was able to redirect substantial funding in the development of vaccines, particularly Moderna and AstroZeneca, when the pandemic struck and the Virus was isolated. Funding was also provided by CEPI to the University of Queensland for its ultimately failed vaccine. Considering the hype surrounding this group, perhaps more reliance was placed on its success than should have been. In any event, it left Australia with very few vaccine paddles, later in 2020. At that time Australia was basking in its success of suppression of the Virus. The children on the beach watching a Punch and Judy show. The sign against the beach stage read “Now in its 290th year”.

The children on the beach watching a Punch and Judy show. The sign against the beach stage read “Now in its 290th year”. In 1918 the community was hit by the influenza pandemic which, some say, never really went away. It just became attenuated; but there have been pandemic years. I remember the Asian flu pandemic in 1957 because I ended up in Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. There have been outbreaks since, all caused by descendants of the Spanish flu virus, generally milder and seasonally self-limited. In summary, seasonal influenza has tended to kill the oldest and youngest in a society but has been less virulent since the 1918 pandemic – roughly half of those who died were men and women in their 20s and 30s, in the prime of their lives.

In 1918 the community was hit by the influenza pandemic which, some say, never really went away. It just became attenuated; but there have been pandemic years. I remember the Asian flu pandemic in 1957 because I ended up in Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. There have been outbreaks since, all caused by descendants of the Spanish flu virus, generally milder and seasonally self-limited. In summary, seasonal influenza has tended to kill the oldest and youngest in a society but has been less virulent since the 1918 pandemic – roughly half of those who died were men and women in their 20s and 30s, in the prime of their lives.

As I schoolboy I went to the Olympic Games in 1956. I was sports mad and there I was, in the queue 18 months before, on the day ticket sales opened. I am there staring at the camera when I was snapped by the National Geographic magazine photographer just after I had purchased my tickets. The most expensive tickets for the opening ceremony cost six guineas, but none of these were on sale for the “unwashed” even on the opening day. After alI, I was not very far back in the queue which snaked up Lonsdale Street away from the retail store Myers.

As I schoolboy I went to the Olympic Games in 1956. I was sports mad and there I was, in the queue 18 months before, on the day ticket sales opened. I am there staring at the camera when I was snapped by the National Geographic magazine photographer just after I had purchased my tickets. The most expensive tickets for the opening ceremony cost six guineas, but none of these were on sale for the “unwashed” even on the opening day. After alI, I was not very far back in the queue which snaked up Lonsdale Street away from the retail store Myers.

The American automobiles around the streets were remnants of the fifties. They had become a tourist attraction. We were driven about in a sky blue Ford Mercury, but mostly we bussed around the various locations to see a variety of health facilities in what appeared to be a school bus.

The American automobiles around the streets were remnants of the fifties. They had become a tourist attraction. We were driven about in a sky blue Ford Mercury, but mostly we bussed around the various locations to see a variety of health facilities in what appeared to be a school bus. Needless to say, this group of health professionals had a number, somewhat incongruously, who went off to buy that other commodity for which Cuba is famous – the cigar. Together with Cuban rum, cigars were still a prohibited import into the USA. There were constant warnings that the customs would be there, searching for any sign of Cuban tobacco leaf or the smell of rum. The funny thing was when we arrived back in Miami at the end of the week, there was not a customs officer in sight. Irony on a number of levels.

Needless to say, this group of health professionals had a number, somewhat incongruously, who went off to buy that other commodity for which Cuba is famous – the cigar. Together with Cuban rum, cigars were still a prohibited import into the USA. There were constant warnings that the customs would be there, searching for any sign of Cuban tobacco leaf or the smell of rum. The funny thing was when we arrived back in Miami at the end of the week, there was not a customs officer in sight. Irony on a number of levels.