This is my 88th blog. I have not missed a week – and the sequential naming of the Modest Expectations to reflect that number in some way. 1988 – the Bicentenary of this Nation was quite a year. I received funding from the Commonwealth Department of Health to write a book where I asked a number of health professionals how and why they were there in Australia in 1988, at the time of the Bicentenary. It was called “Portraits in Australian Health” – not a particularly riveting title.

This is my 88th blog. I have not missed a week – and the sequential naming of the Modest Expectations to reflect that number in some way. 1988 – the Bicentenary of this Nation was quite a year. I received funding from the Commonwealth Department of Health to write a book where I asked a number of health professionals how and why they were there in Australia in 1988, at the time of the Bicentenary. It was called “Portraits in Australian Health” – not a particularly riveting title.

However, what I wanted to see in their recounting of their lives was why at that point of Australia’s history, they were where they were. The backdrop to each of the lives of those interviewed was Australia.

This idea was expanded by the BBC in 2004 where they identified celebrities and took them through their genealogical paces with a predictable chorus of “gosh” and “unbelievable” and “who would know?” as each of the atavistic eggs was unscrambled. All beautifully orchestrated. By and large the people chosen were performers, who could act the part of the stunned inheritors of their family helix.

I suspect that the budget for these TV shows is generous, because it showed that people are curious about other people. “Celebrity” gossip is the fare of the magazines which concentrate on a vague representation of the truth. The BBC, as did I, actually did research!

My concept was relatively simple: sit the person down and let him or her talk. Some I had known before; others only by reputation and I tried to achieve some sort of balance. A few I regret using; others were incredibly important in tracing the path of the reason for their being health professionals and providing “a tapestry” for the 200 years.

However, in retrospect there were at least two major omissions in people from certain categories. There is no dentist in the book; the person I had singled out, because of his long family association with the profession declined to be interviewed; he died not so long after of cancer. That was the only rejection that I remember.

The other omission which, if I could I would rectify, was an Aboriginal person with a health background. On reflection, I should have asked Naomi Mayers, who was the Chief Executive Officer of the Redfern Aboriginal Service. Much later I had lunch with her and a number of Aboriginal people in Redfern and even then I had no inkling of her link to the Aboriginal singing group, the Sapphires. But I didn’t identify her and I regret it.

However, as I found as I met more and more Aboriginals, there was a rich cultural heritage, much of which was hidden from whitefellas. I have always been sceptical of the historical importance of bush tucker, which has acquired a following among well-heeled whitefellas. Much of the tucker available would hardly merit a feed, so tiny are the individual berry, fruit and the other flavouring agents.

However, what I have found very interesting and have met on various occasions were ngangkeri, the medicine men. When I was often visiting Wilcannia in the early 90s, I heard about the kadaitcha men who were still around. However, that was all, and after all “the feathered foot” left no trace; so how would a whitefella find out more. It was all intriguing and the more I was accepted the less I knew.

The Aboriginal society is “many nations” – after all, look at the difference in the culture across the nation. The problem is that in the confected restoration of Aboriginal culture, the diverse nature of the culture has been increasingly homogenised. That cannot be criticised as it recognises that the Aboriginal culture is not static; and given the improvement in communication and educational opportunities it is unsurprising that the Aboriginal is becoming less and less regionally distinctive. Having said this there will always be nests of such traditional culture.

The conundrum for such communities is how to preserve culture against the predatory nature of a culture of booze, fast foods , “black milk” and all the churning of this faddish instant googled-eyed Facebook age – yet not denying progress.

It would be a challenge now to find the Aboriginal health professional who would fit easily into a portrait of Australian health. In 1988, it was only four years since the first Aboriginal doctor graduated.

Charlie Perkins

I was thinking about the first time I met Charlie. It was obviously in 1973, and up until that time, all I had heard about him was that he participated in the Freedom Ride to confront rural NSW concerning Aboriginal rights. To the urban Australian living in comfortable suburbia, Aboriginals were invisible.

As I child I remember receiving Church Missionary Society pamphlets about all those nice little Aboriginal children running around in Roper River Mission – so happy to be one of God’s lambkins. It was all so foreign, and the first time I saw real, live Aboriginal children was years later when I went with my parents to Central Australia. Part of the tour was a visit to the then Lutheran Hermannsberg Mission. We white children eyed off the Aboriginal children, who did likewise and giggled at this awkward bunch of kids from down south. Nobody encouraged us to mix and eventually we got back on the bus and left. There were also the blackfella children in the settlements along the old Ghan route which then wound through the floodplain country and terminated in Alice Springs.

I remember I insisted in Alice Springs that my parents buy me a black ten-gallon stockman’s hat, and even though I have a large “scone”, the hat came down over my ears. My other purchase caused all sorts of bother, and when it was brought home it had its own “cordon sanitaire” because the ochre covering this large bowl was very thick and had never been fixed, so if you touched it, the ochre always stained your hands. Eventually the bowl disappeared from the house – as did the hat.

However, there were several episodes of the ABC lunchtime serial “Blue Hills”, which have remained with me. These concerned a storyline where Aboriginal Heritage would lead to “a throwback” situation which meant that apparently white parents with Aboriginal blood could be confronted with a “piccaninny” child. Then, as the serial progressed, what relief – Aboriginal heritage was diluted – absorbed – assimilated – and joy of joy – no return to the noble savage. Well, that was the gist of the serial story and reflected the attitude of Australian suburbia superficially encased by a white picket fence of normality.

There were three films that I remember in my early childhood leading into teenage years. All had a variable effect on the development of my attitudes towards Aboriginal people. After all, I grew up in a world dismissive of our landlords. The 1947 film Bush Christmas starred a 12 year old Aboriginal boy from Woorabinda in Queensland, Neza Saunders, who showed how to eat a witchetty grub. At that moment, I wanted one to eat. A gourmet meal of witchetty grubs sadly still remains on my to do list.

The film Pinky explored the plight of the light-coloured black American in a 1949 film of the same name. I remember in the context of a society which, despite the pious comments of my schoolteacher, remained at its base racist. We, as children because we grew up in a homogeneous culture, did not have the basic experience to question. However, for me, it instilled in me a sense of unease, the word “miscegenation” still unknown to me.

This unease was reinforced by Jedda, a film where the central tragedy of the Aboriginal was played out in a Charles Chauvel melodrama. Jedda was such a beautiful young image for myself, a teenage boy. Years later I went to Utopia, an Alyawarre settlement on the Sandover Highway. As an Alyawarre woman, she had grown up there and later had a troubled relationship with the community. I did speak to her on the telephone but she was away when I stayed in Utopia.

It was still a long time from Jedda before I was to run across Charlie Perkins. I do not know why but we had an immediate empathy. One problem I had noted was that Aboriginal reticence meant that you had to learn to speak through the silences. As one of my Aboriginal brothers would say, the non-verbal conversations with the various vocal clicks was difficult for whitefellas so used to voice communications. The other manifestation that was clear from a growing association with Aboriginal people was if a particular government meeting was thought irrelevant, the Aboriginal representative just did not turn up, but as the Aboriginals have come in from the fringe that dynamic changed. Aboriginal people can recognise tokenism.

In 1973 in Parliament House it was demonstrated very clearly that here was a nation wrestling with the Menzies’ legacy and in particular the engagement in Vietnam. Whitlam terminated Australian involvement, and both he and the Leader of the Opposition, Bill Snedden visited China that year. Snedden was privately concerned with the lack of involvement with Aboriginal People, since even though the 1967 referendum was an overwhelming affirmation of Aboriginal rights that was not easily translated into a workable outcome for our society.

Charlie Perkins, when he was young, had this busy enthusiasm about him. Snedden suggested that I might try and talk to him. The easiest way to talk to him was around the campfire which the Aboriginals had started outside Parliament House. We got on well from the start and spent a lot of time yarning around the fire. To me it was symbolic of establishing an understanding, and Charlie was appreciative that somebody from the Opposition had bothered to brave the fireside. It did not take long for the message to come back from one of the Nats who had seen me with Charlie around the fire saying: “Who’s that Communist working for Snedden?” The other occasion that I well remember was walking with Charlie across King’s Hall one evening, when Mick Young with Eric Walsh came up and said to Charlie without acknowledging me, “You coming to dinner, Charlie?” Charlie shot back, “No, I’m going to have a meal with Jack Best.” These are in the order of things inconsequential. Both Charlie and I wanted a better world and we threw out ideas, most of which drifted off in the camp fire smoke.

So did we, drifted away from one another. Much later when I met him when he was a senior public servant, he seemed to have lost much of this zest for life, but then that happens when you become a fully-fledged bureaucrat.

However, he was also fighting renal failure.

I read Pat Turner’s Charlie Perkins Oration this year, and even though I am not sure I agree with everything she said, she was right in saying that Charlie – the Charlie I knew – never backed down. Yet he showed a willingness to engage in all sides of politics. Later I was to have quite a bit to do with Congress, the Aboriginal Health Service which grew out his early activity in Alice Springs. It is a pity Charlie died while still a relatively young man, succumbing to one of the sequelae of that most deadly infections to Aboriginal people – the streptococcal bacteria.

Conquering that scourge of Aboriginal people still remains. It is not the only one.

Charlie to my mind was the first person who taught me the etiquette of equality of the whitefella in the eyes of the Aboriginal person. I never attained the level that we could have called each other “brother”, but he enriched my life. Aboriginals were not a cute fringe eating witchety grubs, playing in mission dirt or conforming to a stereotype imposed on them.

Thanks, Charlie for being around when you were – brief as it was. However, you opened up a new perspective for me, and in so doing enriched my life in so many ways.

John Kitzhaber Concludes – A New Model for the Nation

A financially sustainable system designed for value and health can take many forms, but it must include five core elements:

- Universal coverage;

- Defined benefits;

- Assumption of risk by providers and accountability for quality and outcomes;

- Capped total cost of care through a global budget indexed to a sustainable growth rate; and

- Cost prevention by addressing the social determinants of health.

Here is one example. Starting with our current public-private financing structure, modify the three large insurance pools that currently define the US healthcare system.

- Pool 1: To achieve universal coverage (element 1), restore the ACA individual mandate but ensure that people have affordable health plans in which to enrol. Expand Medicaid eligibility to include the 28 million people who are currently uninsured or create a new, affordable, publicly subsidized option to offer them. At the same time, move Pool 1 to a CCO-like capitated model that encompasses elements 2 through 5. If coverage in the individual market is unaffordable, those below a certain income level (e.g. 450 percent of the federal poverty level) could buy into Pool 1 with income-based cost sharing, which would make universal coverage more feasible. This is particularly important today as millions of people are losing their employment-based coverage and moving to Medicaid or the individual market.

- Pool 2: Because Original Medicare is still paid through fee-for-service, the program must be moved to a capitated model. One approach would be to create incentives to enrol in a Medicare Advantage Plan (most of which are already capitated) and change the Medicare Advantage Plans that are still fee-for-service to capitated models that meet elements 2 through 4. Because reimbursement would now be based on managing cost and improving health, Medicare Advantage Plans would better incentivize providers to view their patients as a whole through, for example, nutrition counselling or working with social services for safe housing, thereby meeting element 5.

- Pool 3: Allow the remaining markets—employer-sponsored medium and large group and self-insured markets—to operate as they do today, negotiating prices with health plans and using their market power to insist on capitated risk contracts with provider networks. The public sector price negotiations outlined below would provide a benchmark, giving employers additional leverage in negotiating prices in the commercial market. This advantage should be amplified by forming new partnerships with Unions

Continue the transformation by using the consolidated purchasing power of Pools 1 and 2 to negotiate one set of prices for both pools. This would include not only what providers are paid per beneficiary (risk-adjusted according to each beneficiary’s expected care needs) but also prescription drugs, medical devices, laboratory services, imaging, and all the other niche business models that have been established under the fee-for-service model to maximize revenue. This kind of price negotiation is what most large private employers (making up the majority of Pool 3) do today. Public payers should follow suit by using the consolidated purchasing power of the public sector—which is footing an ever-larger part of the bill—to get the best price and value for the United States of America community. If the public sector were so inclined, it would also be possible to both negotiate limits on individuals’ out-of-pocket expenses and ensure there are no caps on annual or lifetime benefits.

The result would be a new system of universal coverage built on our current public-private financing structure. With the majority of Americans in some form of capitated risk model, this new system (1) reduces the total cost of care through price negotiations, a global budget indexed to a sustainable growth rate, and provider accountability for quality outcomes; (2) preserves consumer choice and allows current insurers to compete for Pools 1 and 2 in a restructured market; and (3) delivers more and more value and health because it requires strategic, long-term, effective investments in the social determinants of health.

This is merely one way to design a new, health-focused, financially sustainable system. There are others. My objective here is not to advocate for the example I have just outlined here, but rather to spark a new debate that will lead to a better system. Instead of being constrained by what currently exists, we need to start with our objective, agree on essential elements, and then let the contours of the new system emerge. Long-term, this will serve us better than starting with a plan that may not meet the criteria needed to achieve our goal. For example, while both Medicare for All and a public option are ways to achieve universal coverage (element 1), neither directly addresses the total cost of care (elements 3 and 4) or focuses on increasing investment in the social determinants of health (element 5). Surely, we can imagine linking the total cost of medical care to a sustainable growth rate within the next few years. Then we can work backward to create a health system that meets the objectives of Democrats by expanding coverage and improving health and meets the objectives of Republicans by reducing the rate of medical inflation through fiscal discipline and responsibility.

COVID-19 and the Urgency of Now

As the healthcare system has become ever more dependent on public debt, its financial underpinnings have become inexorably linked to the capacity of the government to borrow. That capacity has been suddenly and dramatically diminished by COVID-19 and by the business closures and high unemployment resulting from efforts to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

To prevent a complete collapse of the economy, there has been a massive federal intervention to keep credit flowing and to provide loan guarantees and direct payments to businesses and individuals. America will have to spend at least $5 trillion this year alone to sustain our economic infrastructure and to support its unemployed. This will leave us with an unprecedented budget deficit and a national debt approaching $28 trillion—with little or no capacity to absorb the 60 percent growth in health care spending that is projected by 2028 (from $3.7 to $6.2 trillion), especially when prices for medical goods and services are projected to account for 43 percent of that growth.

The pandemic is forcing us into an era of dramatic constraints on the public resources allocated to the healthcare system. Neither the government nor private-sector employers can afford the current system anymore, given the economic losses that both employers and individuals have experienced since February and the massive amount of public debt that has been accumulated just to hold our economy together. At the same time, those parts of the healthcare system that have been hit the hardest by COVID-19 are those most dependent on fee-for-service reimbursement, which exposes the basic flaw in a business model that depends on volume, regardless of the value of the services rendered.

This economic crisis means that, for the first time, the economic interests of workers, employers, the government, and many parts of the healthcare sector are aligned. The time to transform the system is now. We have crossed the Rubicon, and there is no going back. We can either watch our current system unravel, with millions more losing coverage and ever-widening income inequality, or we can work together to design a system that helps stabilize our economy and better serves the needs of the American people.

The Role of Unions

This is the moment for more states, facing huge general fund shortfalls, to move to a CCO-like care model for Medicaid, and for Congress, facing staggering debt, to create incentives for Medicare beneficiaries to enrol in a Medicare Advantage Plan and to move that program to a fully capitated model in which providers assume risk for quality and outcomes. Health professionals should be vocal advocates for both of these changes—and that advocacy should be backed up by the strength of the union movement to bring this model to the commercial market. This will require forging new alliances at the bargaining table between Unions and payers—both public and private.

Coverage of the cost of healthcare is, of course, part of the total compensation package, which means that in collective bargaining, wages are often pitted against health benefits. For public employees, general fund appropriations for healthcare compete not only with general funds for wages but also for essentials like increasing nurse staffing ratios, reducing class sizes, and investing in housing and other social determinants of health. The traditional goal in bargaining over healthcare is to reduce, to the greatest extent possible, out-of-pocket costs for Union members (which is very important).

The problem is that focusing only on this aspect of the total compensation package—without questioning the cost structure, quality, or efficiency of the care being purchased—suppresses wage growth. Without aggressively challenging the cost structure and value of the healthcare being purchased, the dollars spent on rising premiums flow into a system that redistributes them upward, taking money from the pockets of working Americans to enrich the profits of large corporations and wealthy individuals (further exacerbating income inequality).

A CCO-like model would be better because it caps the total cost of care without sacrificing quality and it realizes savings to invest in the social determinants of health—including wages. Particularly for workers making minimum wage or close to it, income is a primary driver of health.

Employees and employers have a shared economic interest in reducing the rate of medical inflation and in focusing on value and health. Providers, for the first time, now have an economic interest in changing the payment model from fee-for-service to capitated because this is the only way they can survive in an era that no longer can sustain debt financing. From the standpoint of the Labour movement, CCO-like models could result in increased wages, better staffing ratios, and more funding for education and other services that are critical to making our society more just.

This need for greater social investment must emphasized. Reducing the total cost of care will assist all working Americans (not just those with union representation) because it will make not only their wages go further but also relieve them of the anxiety of not knowing whether the next illness will push them into bankruptcy. And it will give us, at last, the ability to address the conditions of injustice that underlie disease.

Let’s Begin Now!

Creating a new system with the five core elements will take time. But there is much we must do quickly. Because the economic consequences of the pandemic—particularly the increase in unemployment, with its associated loss of workplace-based coverage—are driving us toward Pool 1 (Medicaid, the uninsured, and the ACA marketplace), this is the logical place to start.

The most urgent coverage problem is for those who are not offered or have lost workplace-based coverage and whose income is too high for Medicaid (above 138 percent of the federal poverty level) but too low to afford the individual market. These struggling individuals are joined by a growing number of underinsured Americans who are technically covered by employer-sponsored plans but face copayments and deductibles so high that for all practical purposes they are uninsured. People of color—particularly Black, Hispanic, and Native American people—make up disproportionate numbers of both of these groups.

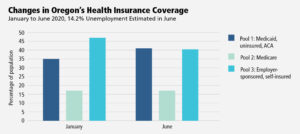

The state of Oregon offers an illustration of both the problem and the opportunity. By the end of April, 266,600 Oregonians had lost their jobs (an unemployment rate of 14.2 percent). An estimated 215,800 of these people will be eligible for Medicaid, 20,500 will move to the ACA exchanges, and 30,300 will remain uninsured.20 Because Medicaid is entirely financed with public resources and the ACA exchanges are heavily subsidized with public dollars, this amounts to a dramatic increase in public sector financing of healthcare. In terms of the healthcare model proposed in this essay, Oregon’s Pool 1 is expected to increase from 34.9 percent to 41.3 percent of the state’s population over a few months.

Furthermore, if 80 percent of those who lack health coverage in Oregon made use of coverage for which they are currently eligible—Medicaid or the subsidies available through the ACA marketplace—the number of Oregonians who are uninsured would drop from almost 250,000 to 34,000 (from 6.2 percent to < 1 percent). The only obstacle is the total cost of care.

Since states are facing enormous budget deficits and the federal government is facing a looming debt crisis, it is imperative that shifts toward public financing be accompanied by effective mechanisms to reduce the total cost of care through global budgets (indexed to a sustainable growth rate, with providers at risk for quality and outcomes). At the same time, such global budgets are now more appealing to many hospitals and primary care practices because of the sharp loss of revenue among those with fee-for-service models.

Mouse Whisper

I know we were all keen on Amy Klobucher, when she seemed to be the most articulate candidate back in those days when the Democratic race was like the first at Rosehill. She dropped out, and although considered as Biden’s running mate, she missed out here also to Kamala Harris.

However, the most final reason for her not getting the nod was:

She’s from Minnesota!

In explanation, no Minnesotan has ever made President, and such a judgement tends to stick once voiced. At least Barcelona is not in Minnesota.