I always remember that mixture of nihilist and smart-arse sage, Reg Withers, ruminating on the cupboard we had in our office which was stacked full of anti-abortion letters to the then Leader of the Opposition, Bill Snedden. This was in early 1973, when this matter was subject to parliamentary debate. He looked with some disdain at the overflowing cupboard and the 100,000 letters. He then said there were 13 million people in Australia and this protest therefore constituted only a small fraction of the voters. Yet it spooked the whole of the Coalition into voting for the anti-abortion crowd. Even when Andrew Peacock flamboyantly stood up, I am sure with the intention of leading a group of Coalition members into the pro-abortion vote, but when he looked round and saw he had no support except from the Opposition staffers, he quietly sat down.

I had the same feeling as Withers concerning the mention being made of the number of those who filed by the body of Benedict XVI lying in State in Rome last week. Maybe up to 200,000, being generous in the number who did, but the celebrities were few, especially from his country, Germany. I noticed that they were not burying him with his famed red slippers. Funny, the things you notice, but I found out later he had to relinquish the red slippers with his pontificate. Funny, in another way!

The denominator – us – seemed indifferent to the death of this man. This denominator numbering billions would form, I suspect, an indigestible number for the Roman Catholic Church, if it chewed it over for a moment.

Many matters have always worried me about Cardinal Ratzinger. Perhaps it was his opposition to the worker priest movement. Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI said very clearly,

“Clerics must not “surrender to the temptation of reducing [the priesthood] to predominant cultural models.” In today’s world, “widespread secularization” has cut into appreciation for the priest in his pastoral and ministerial role and accentuated his public activities. There is great need for priests who speak of God to the world and who present the world to God; men not subject to ephemeral cultural fashions, but capable of authentically living the freedom that only the certainty of belonging to God can give.”

The worker Priest movement had originated in France during WWII “putting young priests into secular clothes and letting them work in factories, to regain the confidence of the French working class, which had almost completely abandoned the Catholic faith.”

Then, as Cardinal Ratzinger, he was the warrior against liberation theology, which was sweeping through South America repelled by the fascist regimes, some of which were sheltering Nazi war criminals. Cardinal Ratzinger, the doctrinal enforcer for the Polish Pope, John Paul II, called Liberation Theology a singular heresy. As reported, Cardinal Ratzinger blasted the new movement as a “fundamental threat” to the church and prohibited some of its leading proponents from speaking publicly. In an effort “to clean the Papal stables”, Ratzinger even summoned outspoken priests to Rome and censured them on grounds that they were abandoning the church’s spiritual role for inappropriate socioeconomic activism.

No wonder that the current Pope, the Argentinian Francis I, has exhibited an ambiguity in his relationship with his predecessor.

I have other major concerns and that was the apparent ease with which Cardinal Ratzinger moved from the Nazi Youth into the seminary towards the end of WWII, when Germany was in chaos. Bavaria was one area not spared from the war, unlike much of the Southern Poland of John Paul II, alias Karol Józef Wojtyła. Munich was heavily bombed. It seems that the Church can always produce a couple of Monsignor apologists (the title apparently provides a degree of gravitas) when they want to paper over inconvenient cracks. Thus, Cardinal Ratzinger was in the middle of this chaos as a teenager, but survived. The period needed that papering over.

Contrast the fate of Father Reinisch, the Austrian priest, who just before his execution by the Nazis in 1942 said: “I am a Catholic priest with only the weapons of the Holy Spirit and the Faith; but I know what I am fighting for.” A simple affirmation, no. sophistry. He, together with Franz Jagerstäter, the Austrian conscientious objector, believed his Catholicism was incompatible with giving his oath of loyalty to Hitler, Jagerstäter was guillotined in 1943. This oath to Hitler, from which the Hitler Youth were not exempt, is airbrushed from Cardinal Ratzinger’s biography.

Jagerstäter had been inspired by Father Reinisch. In 2007, the Vatican, through the Bishop of Linz, beatified Jägerstätter, the conscientious objector finally being bestowed with the halo of martyrdom from the Catholic Church. The bishop’s predecessor had tried to talk Jägerstätter out of sacrificing his life for his faith during World War II, and instead, align himself with the Nazis as the Catholic Church hierarchy had done.

Therefore, resistance to the Nazis was hardly a situation where one could disavow the Nazis without retribution, but Cardinal Ratzinger and his elder brother, Georg, seem to have been fortunate in this regard, but then he was only about 18 when he handed in his Nazi Youth credentials and vanished back into the seminary.

There was allegedly a period of being held by the Allied Forces in between these two events – presumably there is documentation to prove that they were held by the Allies. Both Reinisch and Jagerstäter, who were executed, were men and they were Austrian. The point was made to excuse their membership that the Ratzingers were insubordinate when members of the Nazi Youth. As if that attitude would have helped the survival of the young Ratzingers, as members of Hitler Youth? I would have thought not – as they say “pull the other leg and it plays Jingle Bells”.

The younger brother was briefly Archbishop of Munich before he was appointed to Rome by Paul VI, but it was the time when the sexual predatory nature of the Roman Catholic Church was emerging. Cardinal Ratzinger was not blameless. The familiar shuffling of predatory priests under his rule ended up with one notorious predator consigned to an isolated Bavarian village where he plied his sexual trade, destroying at least one life.

Cardinal Ratzinger’s elder brother was ordained and was the choirmaster at the Regensburg Cathedral between 1964 and 1994, and this too seemed to be a hotbed of sexual molestation. Choirmaster Ratzinger the Elder was reported as being unaware of this; or was lying. “Lying” is a word which the Roman Catholic Church seems to hate using, but again when the younger Ratzinger was accused of turning a blind eye also, then the veil of obfuscation (in other words – lying) comes down.

What is clear is the younger Ratzinger tried to keep sexual molestation accusations within the Church and not have them reported to the police. His expertise in rolling out the Roman Catholic mystique was second to none. He was smart enough to cherry-pick obvious and completely indefensible targets, such as Father Maciel, the Mexican priest, who founded the Legion of Christ and the Regnum Christi movement of which he was its general director from 1941 to 2005. With the declaration of ridding the Church of “filth”, the then Cardinal Ratzinger heralded his intention to pursue Maciel, who was known to have molested his seminarians. The newly minted Benedict XVI was able to force him to relinquish his position. Never defrocked, Maciel died conveniently in 2008 after which his practical views on priest celibacy were also revealed, having fathered six children from a number of relationships.

I first became aware of Cardinal Ratzinger years ago when one of my Roman Catholic acquaintances quipped about a cartoon of Archbishop Ratzinger immersed in a pool of sewage so only his head and neck was showing, but he was smiling. I asked “why?”, as I was supposed to do, so my acquaintance could insert the “killer line”, by saying “He is standing on Hans Küng’s head.”

Hans Küng was a liberal Swiss Catholic theologian, a contemporary of the aforesaid Ratzinger, who was censored in 1979 and essentially removed from The Church. My acquaintance thought the quip very funny. I didn’t.

Doctor Goes Walkabout

The European invasion of the outback destroyed this balance between man and nature for ever. The sheep and cattle of the settlers ate up the ground cover on which the natural food of the Aborigines existed; the kangaroos and other bush creatures were shot for sport or because they ate the feed needed for stock pasture, and the soaks and waterholes were taken over by the intruders. Also, the sacred places of the tribesmen were profaned by the white men.

Charles Duguid, who lived to 102, wrote these words. He was born in the same year as my grandmother in 1884. Thus, I have a personal acquaintance with the age in which he lived. Duguid wrote this reminiscence, “Doctor Goes Walkabout”, when he was 82. It detailed his life from a Scottish childhood and early adult life as a young doctor.

Charles Duguid, who lived to 102, wrote these words. He was born in the same year as my grandmother in 1884. Thus, I have a personal acquaintance with the age in which he lived. Duguid wrote this reminiscence, “Doctor Goes Walkabout”, when he was 82. It detailed his life from a Scottish childhood and early adult life as a young doctor.

The book opens with a description of the ingenuity of doctors at a time when there were no off-the-shelf remedies. Faced with a girl with quinsy where the pain prevented her from opening her mouth, his grandfather doctor ordered a poker to be heated until the point glowed red. He then approached the girl menacingly. The girl screamed, the abscess broke, the quinsy had been cured without him placing a hand on the patient. Never mind the morbidity associated with the tactic. It was anecdote -the stuff of medical recall – often where sensitivity is subordinate. This book is no different.

However, I found the book informative because this was a man who graduated from Glasgow University at the end of 1909, and then when he first came to Australia practised in the Victorian Wimmera town of Minyip, which I knew well. He paints a dark picture of the life there, where he witnessed a strychnine poisoning – a murder carried out before his uncomprehending gaze. Later, following a conversation with a neighbouring doctor, he realised he had been duped by a family conspiracy.

His book portrays a devout Presbyterian who was always very close to his church, with all its basic conservatism. He saw action in Palestine in WW1, and amid the carnage with which he was expected to deal was his search for his brother, Willie, who he found was coincidently stationed in the same part of Palestine. Eventually, the two meet, after Charles had gone on an extensive search for him. They talk through the night, little knowing that this would be the last time he would see his brother, killed soon after.

His description of his first wife’s death is succinct. He dismisses it in a sentence. Coming home from England, she had an intracranial haemorrhage and died; by the end of the page, he had married again, to a teacher he met at the annual prefect’s dance at the Presbyterian Girl’s College in Adelaide, which eventually served as base. It was a wee bit offhand I thought, given the description of his efforts to seek out his brother. But then I suspect he was very stiff upper lip.

There in Adelaide he set up his practice eventually, but he was always off somewhere; and soon he was concerning himself with Northern South Australia (the Pitjantjatjara Lands). His relationship seems very similar to that which occurred later with Paul Torzillo; visiting, providing advice and support, but never practising among them for an extended period. Duguid’s view of his contemporaries I found interesting. He liked Pastor Albrecht and the work that was done at Hermannsburg. The Lutheran influence on Aboriginal life probably has been discarded by the present view as pernicious, part of the “whitefella” mission culture. Yet Duguid noted in his book was that of all the outback missions only Hermannsburg looked after full-blood Aborigines in the 1930s.

Duguid was less charitable about the Australian Inland Mission (AIM). He did not care for Flynn abrogating the initials from the Aborigines Inland Mission (AIM) which had been founded some years before. Flynn did not care.

Duguid and Flynn disliked one another. The author, Brigid Hains has written extensively about the feud between the two men. Thus anything Duguid wrote about Flynn should be taken with that in mind.

Duguid quotes the Director of the Australian Inland Mission, without naming him, as saying: “The A.I.M. is only for white people. You are wasting your time among so many damned dirty niggers.” John Flynn was Superintendent of the AIM at the time, not titled “Director”. Duguid then hastened to say that the AIM did a “splendid job” for the white community, especially for white women. The nurses were the “wellspring” of the Flying Doctor Service, “inspired by the Reverend John Flynn of the AIM” and made possible by the invention of the pedal wireless. Later in the book he describes in 1936 arranging with the “Padre of the AIM” for white children to sit with a group of Aboriginal children. As described, this annoyed the Padre very much. “He rang me, told me that he was making other arrangements for the day, and said, “You’ve invited those children – asking them to sit with niggers”. The chapter ended – no further comment.

The anonymity of these two persons only named by their titles suggests that perhaps Duguid was ascribing a Jekyll and Hyde persona to Flynn. Brigid Hains in her 2006 article makes the same point about Duguid’s view of Flynn.

In 1934, at a Presbyterian Fellowship Conference in Adelaide, Duguid said “the shooting and poisoning of natives that took place in the past are too horrible to recall, and yet occasional happenings of a similar kind still take place for outback areas.” His words were reported as “sweeping allegation by Dr Duguid”. Instead of defending the essence of what he said, he pursued the Adelaide News for wrongful reporting; and he was mortified when the report went further and he received inquiries from the Federal Government. The essence of what he said was true – that these actions against the Aboriginals were still happening at the time he had spoken at this Conference. Yet he was concerned with his personal reputation, rather than confirming the general veracity of what he had said.

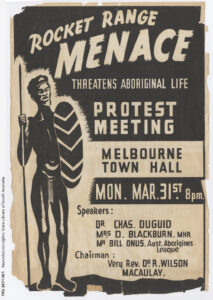

Later in the 1950s he again appeared again more worried about his own standing. When the Government alienated Pitjantjatjara Lands for the Woomera Rocket Range, his reaction was not that of an outraged defender of this people who had befriended. He certainly resigned from the Aboriginal Protection Board when they agreed to Woomera, but his disapproval seemed to have been assuaged by the appointment of a “good white man” by the government – a man who looked after the sheep at the Ernabella Station as the Aboriginal Protector. He was “ideally suited to the job”. I am not sure that Duguid realised how that could be interpreted, as likening the Aboriginal people to sheep. But remember, for the devout, a reference to “sheep” is not derogatory.

Later in the 1950s he again appeared again more worried about his own standing. When the Government alienated Pitjantjatjara Lands for the Woomera Rocket Range, his reaction was not that of an outraged defender of this people who had befriended. He certainly resigned from the Aboriginal Protection Board when they agreed to Woomera, but his disapproval seemed to have been assuaged by the appointment of a “good white man” by the government – a man who looked after the sheep at the Ernabella Station as the Aboriginal Protector. He was “ideally suited to the job”. I am not sure that Duguid realised how that could be interpreted, as likening the Aboriginal people to sheep. But remember, for the devout, a reference to “sheep” is not derogatory.

He should have taken a stand, but that was not his nature – the quintessential man of reason. As he progressed through life, he still expressed concern for Aborigines but did nothing that might offend a country inured to the thinking that Aboriginals were relics of the Stone Age.

In the end, despite his long life and his good intentions, and a clear insight about the treatment of the Aboriginal people, I doubt he left much of a legacy, except in his writing. What can be said is that he tried, but his conservativism, his paternalism and his concern about other people’s opinion probably inhibited his effect on public policy; but at least he never referred to Aboriginal people as “niggers”.

In other words, Australia may have expunged such words, but given the referendum this year, how far has the country really progressed from the times of Duguid?

O Verão de 42 (The Summer of ’42)

- Essa canção é tão bela, transmite uma harmonia tão grande que é até difícil descrever em palavras!!!

- Eu concordo, meu amigo brasileiro

Portuguese is such an evocative language, and I noticed the above comment, and I agreed with it – simple as that.

I had just finished listening to The Summer Knows, the theme song of The Summer of ’42 written and played by the late Michel Legrand. The essay below by Roger Ebert describes for him the inevitability of the distortion of the nostalgia for that time one had a brief relationship with an older woman. It is one of those experiences with all the magic of a fairy tale which, as you grow older and the evocative last words of the film “I never saw her again” exaggerate the poignancy but also the unreality of this experience – not the tragedy that it originally seemed, but a privilege to have briefly believed one was in love. And perhaps one was, but I am no longer the adolescent to verify that emotion.

I had just finished listening to The Summer Knows, the theme song of The Summer of ’42 written and played by the late Michel Legrand. The essay below by Roger Ebert describes for him the inevitability of the distortion of the nostalgia for that time one had a brief relationship with an older woman. It is one of those experiences with all the magic of a fairy tale which, as you grow older and the evocative last words of the film “I never saw her again” exaggerate the poignancy but also the unreality of this experience – not the tragedy that it originally seemed, but a privilege to have briefly believed one was in love. And perhaps one was, but I am no longer the adolescent to verify that emotion.

Robert Ebert, who was the first film critic to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1975, wrote this brilliant piece about the film; brilliant in being flashy rather than being brilliant in his insights because I suspect it probably never happened to him. The background stuff which he describes is only mortar holding the film together but contributing very little. The action between the youth and the older woman is the centrepiece, which needs to be dissected carefully and laid out, because it has a fine grain and yet a longing for something that doesn’t exist. Yet so important to build the romantic cushion, which some would call soul and others cloisters upon which to gaze upon long ago.

Nevertheless, even though I may disagree in part with his piece, it is worth reading both as background to the film and as a piece of fine writing.

Word comes to the woman that her husband has been killed in action, and almost wordlessly she takes the adolescent boy to her bed that very same night. The next day she is gone, leaving behind a note in which she gently declines to comment on the meaning of their experience — suggesting that perhaps, with time, it will take on an appropriate meaning of its own for the boy.

The problem is that it doesn’t. Robert Mulligan’s “Summer of ’42” is constructed to suggest that during that summer an event happened after which the boy was never the same. But we have to be content with an adult narrator who tells us this about himself; we never do learn how the boy, as a boy, put it together for himself. The fault may lie in the movie’s obsession with nostalgia. The movie isn’t set up to tell a story about a boy who was young in the summer of 1942; it insists on presenting itself, instead, as an adult memory of that long-ago summer. We don’t learn very much about the boy because the movie’s adult point of view refuses to come to terms with him.

Nostalgia is used as a distancing device — to keep us safely insulated from the boy’s immediate grief, love, and passion. “Summer of ’42” seems to be suggesting, between its frames, that since all these things happened long ago and far away, in a world of meat rationing and old Unguentine ads and black Hudsons with running boards and theories about the care and use of rubbers, that the boy’s experience is somehow less intensely human.

The movie fairly drips with what’s supposed to pass for taste and restraint; the love scene itself, for example, is filmed in a stubbornly minor key (as if, here again, Mulligan was trying to turn ice into slush, or an immediately felt human experience into a sort of vague and gentle memory). But in the scenes that produce the most laughs — the hero’s embarrassment in the drugstore, or his friend’s sexual initiation on the beach, or their double date at the movies — “Summer of ’42” isn’t restrained at all.

That drugstore scene, for example. “Second City” has had at least two versions of the sketch where an adolescent tries to whisper his order for Trojans to a loud, unsympathetic druggist. This will do as comedy revue material; but “Summer of ’42” handles the material on exactly the same level, breaking step with the movie’s cadence to get some easy laughs. Same with the double date scene, which is crude in comparison with Frank Perry’s similar scene in “Last Summer”.

What we’re left with are some beautifully produced and photographed notes toward a movie. Mulligan has succeeded in convincing us that his movie remembers and understands the wartime summer of 1942. He is very good, too, at trying to convince us that adolescence was somehow more innocent then. But anyone who has ever been an adolescent — and every adult has — will remember that it is hardly ever easy-going, in 1942 or any other year, and that although it may seem innocent when we remember it nostalgically, at the time it felt like an agonizingly prolonged fall from grace.

As she was going through the family papers

Today, my wife, Janine found out that her great-great-great grandfather, Samuel Hoffmann, was a member of Blücher’s army, which fought at the Battle of Waterloo. He was 20 years old at the time but stated to be a surgeon. He emigrated to Australia in 1847 with his wife and nine children to escape the Lutheran persecution initiated by the Calvinist King of Prussia, Frederick III. The Hoffmanns came from Silesia, the Centre of the Old Lutherans who had refused to buckle to the King’s decree for unification of all the Protestant Churches.

I had a relative who was in the British Forces at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, but Waterloo…!

Mouse Whisper

The U.S. will fund the purchase of 18 new High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) for Ukraine, more than doubling the number of launchers that have arguably altered the face of the war in Ukraine. The Ukraine now has an almost 3,000 kilometre border with Russia, of which about 10 per cent is a sea border.

The Australian coastline (the sea border) is nearly 26,000 kilometres. How many HIMARS does the USA have? The US Army has 363 and the Marines 47. Singapore and Romania each have 18 and Jordan has 12. The Poles ordered 20 in 2019 and want 200 more, and it has been reported the USA Defence Forces are said to want another 500 by 2028.

To get comparable protection, it would seem that Australia will need all of these above. After all, Singapore’s coastline is 193 kilometres and it has 18 of these weapons!

But being a Mouse, have I got my calculation wrong?