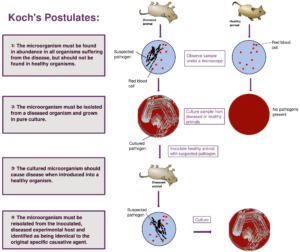

As the pandemic has ploughed on, there is a new collective noun for the experts clamouring for media exposure – an irritation of epidemiologists. After more than 15 months of COVID, the endless stream of epidemiologists called upon to express opinions on television have variously inspired and annoyed, but more often have provided a confusing opinion. For me, the soft-spoken Marie-Louise McLaws, whose family motto is “Spectemur agendo” meaning “we are judged by our actions”, is one such example. Marie-Louise is probably judged by her talking head television profile and she obviously has her fans.

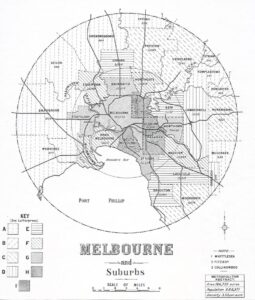

Nevertheless, she has made a pertinent observation as to the vulnerability of Victoria, particularly Melbourne, to the spread of the COVID-19 virus. It is a matter of geography – the ease with which people can move around there as distinct from other major cities in Australia. Others are chiming in with stochastic analysis, a fancy name to define randomness of these events. Perhaps she has been over-enthusiastic in emphasising some other differences, which probably don’t exist, but the geography argument is a strong one, and the outer suburbs of Melbourne do contain many migrant groups.

Take the Indian population, for instance; they are clustered on opposite sides of Melbourne, which is the favoured destination of Indian migrants over Sydney. If you believe the blurb, that is:

“Indians living in Melbourne love:

- living in Melbourne’s suburbs with safe, accessible transport

- local supermarkets, Indian grocery stores and restaurants

- Melbourne’s festivals, museums and cultural events

- Victoria’s world-class education system

- dining out in Melbourne’s renowned restaurants.

All conducive to a very mobile lifestyle, and there are over 56,000 Indian-born Australians in Melbourne, thus about three per cent of Melbourne’s population. Sydney has a smaller population, and it is concentrated in Harris Park and surrounding suburbs in Sydney’s west. In this century up to 2019, Indian migration was the largest in percentage terms. People should not be coy about country of origin, especially when so many still have strong family links to a country where the virus spread has been out of control. In the midst of a pandemic, such demographic information is important.

I always remember a description of Brisbane, “If Rome was built on seven hills, Brisbane was built on seventy-seven”. Sydney by its geography is also compartmented, and this was well shown in the COVID-19 outbreak on the northern beaches of that city in December last year. This outbreak was easily contained.

However, when the infected were allowed to move around in that well known stochastic process, Brownian movement, as they were from the disembarkation of the Ruby Princess in the middle of the city with access to multiple transport links, then one could call the process, the Berekjlian, after the presiding Premier of the time. But normally it is far more challenging to move around Brisbane and Sydney than Melbourne.

In regard to accessibility, take one suburb of Melbourne, Hawthorn. There are three tram lines running through it and a railway line with at least two stations serving Hawthorn. There are also buses, and the increasing use of private buses to ferry private school children to and from school, Hawthorn and the neighbouring suburbs are a large scholastic reservoir. Added to this Melbourne is very easy to move around inside the rapidly expanding perimeter. The only barrier is the Great Dividing Range which only provides a hurdle to travel in the Dandenongs component. Otherwise, all the other sectors have major highways radiating out from Melbourne, which mean travel is easy.

In Melbourne, some talk nostalgically about living in a “village” rather than a “suburb”. I would dispute that.

At last the Federal Government, a Federal Government dominated by one Sydneysider who lives in an enclave called the Shire, has buckled to the obvious need to have a custom-built quarantine centre in Victoria close to Melbourne. Hopefully more objectivity will be applied to the tendering than much of the scandalous way the Government has gone about business over the past three years. Whether Avalon is the right place or not, it is on pre-existing Commonwealth land and relatively close to Melbourne.

I wonder though if the invaders were not “micro-marauders”, not easily identifiable, would the Governments be adopting the seemingly leisurely pace to get this centre built. Maybe photo-opportunity trips will accelerate the process. In the Northern Territory or even South to Tocumwal in NSW, one can see how quickly facilities, hospitals, airstrips and even a highway were built when the Japanese were on the horizon.

Waleed Aly has waded into the conversation, questioning the validity of singling Melbourne out. As usual he writes persuasively, but I suggest that he reinforces the point that having hotel quarantine in the middle of city with the easiest means of spread of anything, be it people or viruses, is just asking for trouble.

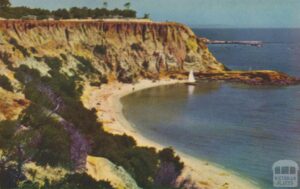

He singles out Black Rock as a Melbourne suburb where lockdown was not required. This suburb and the adjoining Beaumaris were developed later from bushland. They lie beyond the terminus of both tram and bus, and therefore have some the characteristics of the Sydney northern beaches suburbs. The distinguishing feature was its isolation. The way it was isolated had a distinct elite character and elitism discourages easy movement.

Despite the intervention of Waleed, as an epidemiologist, Professor McLaws, you made a good point, but in your enthusiasm to prove a point you probably went a wee bit too far.

Scars of 56

Since my Chinese exploits are receiving some interest, here is an excerpt of a book I hope to publish later this year subtitled, “When we were not too Young”.

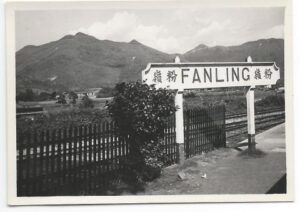

Over dinner my father continued to repeat that he wanted to “see China”, whatever that meant, and the only way to “see China” from his point of view was to take the train to the border at Lo Wu and stare across into the country. However, it became clear when he asked if that were possible that, although the train might go through to Lo Wu, all the passengers had to get off the train at Fan Ling, which was about four miles inside the border. Nevertheless, we bought tickets because my father said: “…you never know”. If nothing else, he was awake to serendipitous opportunity.

He had also thought of going across to Macau, which required an overnight boat trip. Macau was then a seedy remnant of the Portuguese empire. He wondered if it would be easier to get closer to China if he went there, but when he inquired about that feasibility, he was quickly disabused. There was a lawless element there and it would not be worth being exposed as a lone traveller. I thought I heard the word “triad” mentioned in the conversation.

So here we were about to board the train to Lo Wu. The train with the steam-driven locomotive was regulation pre-war with cracked leather seats in the carriages and the views through the windows made even greyer by the grime on the windows.

The carriage was empty apart from ourselves.

The city straggled away into the New Territories and into a quilt of paddy fields. There were distant mountains, which my father said were probably in China. He stood up and walked along the corridor hoping to get a better view. He came back and confirmed that the mountains were on the Chinese side of the border. I am not sure how he knew but, as always, he was authoritative.

The train pulled into Fan Ling and the conductor came along telling us to get off. I could feel very clearly my father’s reluctance as he stood up, and slowly climbed down onto the station. At the end of the station, there were a number of Chinese soldiers in green jackets and trousers. They did not seem to be armed but symbolized a line of demarcation between themselves and the Hong Kong constabulary, who were fitted out like London policemen acting with the departing passengers as if they were directing traffic in The Strand.

The Forbidden Land lay beyond – the view entombed in the wintry sunlight.

However, there was one person standing on the station close to the train. He was wearing a hat, scarf and gabardine raincoat. The scarf was drawn up to partially conceal his face He looked across the station and, in an Australian accent, called my father’s name. My father looked up, startled at the recognition. He did not immediately recognize the figure, who lit a cigarette, for a brief moment illuminating his bespectacled face. My father strode up the platform. They shook hands and for five minutes they engaged in what appeared to be animated conversation, my father pointing toward the Chinese border.

I was distracted by a middle-aged Chinese man, who sidled up to me with his bicycle. In broken English, he said he would take me to the border on his bicycle. It would not cost much; and I could see what China was really like. I hesitated. My father was still in deep conversation, and I looked at the bicycle. Was he going to “dink” me? There seemed to be no other way that I could get on the bicycle, unless I hired it from him.

I looked out over the rice fields and through the line of houses, which clustered below the station. I could make out the road running north-south which presumably went towards the border.

“Can I take your bicycle and bring it back?”

The man with the bicycle hesitated. Then he pushed it towards me especially as he saw that I had US dollars in my hand.

“What in God’s name are you doing, John?”

“I thought you wanted to go to the border.”

“On that?” My father’s face split into one of his thin-lipped smiles, which you rarely saw unless he was about to launch into an invective against somebody.

The ferocity of the “On that” seemed to frighten the man with the bicycle, as he took a step back.

“So you are seen pedaling to God knows where wearing completely inadequate gear. If you don’t freeze to death, you are liable to be either shot or captured. John, I suppose you think that all that there will be is a bit of barbed wire and smiling soldiers. Does not work that way – and the last thing I want to happen is my son dead or interned. The last thing I need,” he repeated, “is for my son to be the centre of an international incident.”

I thought my father was a bit over the top, but I suddenly felt very cold. After all, it was winter and the threadbare trees along the road towards China bent in the wind as if derisively waving me on in my fruitless endeavour.

My father gestured towards the retreating figure on the bicycle. There was no need to wave him away. He disappeared from sight off the edge of the platform.

My father turned and looked back to see the man with whom he had been talking climb onto the train. The Chinese troops did not move.

My father gestured. “That John is a safer way of travel, but unfortunately you need to be credentialed, as Ted is. I believe he is off to Beijing. However mark my words, I shall get over the border in the next ten years – and more than once.”

We waited for the train to come back. My father was suitably vague about who Ted was, but he worked with a friend of my father who, like Ted, had been a lawyer and, if not a Communist, certainly was a definite shade of cardinal.

My father was always very sure of himself, but I could never fathom his politics.

Postscript: My father did achieve his goal and did go to China – more than once. My father died in 1970 – so it was quite a feat in the 1960s to do just that.

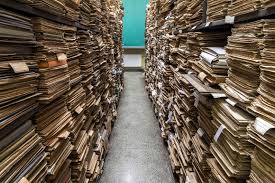

Burning of the Books

Archives are people, and not the great people, but those who otherwise would leave no trace: the workers, the immigrants, the servicemen, the public servants, and, not least, the Indigenous. Of our collecting institutions, the NAA (National Archives of Australia) is the most truly democratic — of the people, by the people, for the people.

Record keeping, furthermore, is fundamental to the protection of citizens and the prevention of harm.

In a recent article in The Australian, a pertinent excerpt is reproduced above, Gideon Haigh has almost said it all about Assistant Treasurer Stoker and her disdain for retention of the archives – hence it follows who cares about the history of the nation? Should it be reduced to dust or why not to a bonfire?

I am reminded of the Futurist movement, which had its genesis in Italy before the First World War, with its disdain for the past and its concentration on the future with an emphasis on technology, bellicosity and patriotism. It is unsurprising given its behaviour that it was closely identified with the rise of Mussolini which they supported. When I say I am reminded of, I don’t mean to say that Assistant Minister Stoker is a simulacrum of the Futurists. Some of them had original ideas in the arts, a talent that the Minister hides under a bitcoin, having dispensed with that idiomatic past, the bushel.

After all, the Nazis refined this destruction of the past with the burning of 25,000 books in Berlin on May 10th 1933 including a significant amount of the Jewish heritage in Germany. Australia is in a delicate position where there are forces which are leading this country down an authoritarian pathway, where there is no collective memory. For years, elements of the Australian Public Service are to deny that any past existed, that corporate memory was a disease not to be confused with selective amnesia – and definitely to ensure the freedom of information was a joke that never existed. The Public Service treads the path of a Futurist movement in inked soaked quills of the Executive Porcupine – or in this country – the Executive Echidna.

David Tune, a former senior bureaucrat, was commissioned in 2019 to review the state of the national archives. He submitted his findings in early 2020; over a year later his review was released, in March this year. The report recommended the government fund a seven-year program to urgently digitise at-risk materials, for a total cost of $67.7 million. “Urgently” is hardly the word to describe Minister Stoker’s response.

Stoker’s attitude unwittingly has placed, even compounded, the Government into an untenable position. The Treasurer, given his own heritage, should be more understanding of the destructive force Stoker is unleashing. Frydenberg should reach into his cash box and find the money for the National Archives. Maybe such money would avoid this metaphorical burning of the Archives.

Stoker by name; stoker by profession? Surely not.

Backroad on the way from Normanton

It all started when I asked Dennis whether he could lend me the 4WD for the weekend. I wanted to check out the medical services in Normanton. There was a South African doctor who recently had arrived in the town, and there had been murmurings about the quality of the services.

To get there you needed to go down the main street of Mount Isa to the Barkly Highway and on to Cloncurry and then turn left onto the Burke Development Road. In the mythology of my family, it was said that my father recently graduated in Commerce from the University of Melbourne, had the opportunity to join a fledging Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services, but it would involve leaving his girlfriend in Melbourne. Love won out; and the Great Depression tested that love as my father tried to find a path through genteel poverty and not on the wing so to speak. This day we did not stop to savour the nostalgia of the job that never was.

By way of explanation, Cloncurry was where the airline flew the inaugural flying doctor service in 1928 – the first commercial flight was generally considered to have been from Longreach to Cloncurry six years earlier.

However, this day we had a five-hour drive to reach Normanton. Normanton is not on the Gulf and there is a further 70 kilometres to Karumba on the Gulf, in those days a centre for the northern prawn industry. The prawns were caught, processed and despatched to Asian destinations direct from the Gulf. Her brother had worked on the prawning trawlers in the Gulf of Carpentaria twenty years before. Her brother in addition to working the trawlers always loved fishing, and barramundi were the prized catch in the Gulf.

Karumba had its own link to the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services; in the late 1930s the town was a refuelling and maintenance stop for the flying boats of the Qantas Empire Airways.

Watching the sun go down sitting on the beach after 500 kilometres drive gazing out to sea evoked a feeling of thirst, and we were on the sand without beer. So we went back to the motel at Normanton, and watched the green tree frogs climb out of the umbrella holder in the middle of the table while we drank our XXXX. We were in the tropics!

The hospital was on the hill away from the township proper. We met the middle-aged doctor and his wife, immigrants from South Africa. They were not in their comfort zone, and the wife was particularly fearful of the fact that there were “blacks” running wild in the town. They had grown up under Apartheid and I wondered why they had left South Africa. Perhaps it was to bring their children up in a predominantly “white” country. The majority of Normanton residents were Aboriginal.

Here they were, isolated from the town, with no intention to mix and looking for the earliest possible escape route. An irrational fear of dark people and an inability to identify – while courteous to us, the authoritarian attitude, albeit racist, can only be suppressed for so long. It was clearly evident in this case.

The trip enabled us to reach the Gulf in a far more pleasant way than Burke and Wills, who had slogged their way along the same route to get to the same destination but died on their way back.

There is another less comfortable route to Normanton from Mount Isa and that is via Lake Julius rather than via Cloncurry. Lake Julius is an important water supply and is a favourite picnic spot for those wanting to have some respite from the mining atmosphere of Mount Isa.

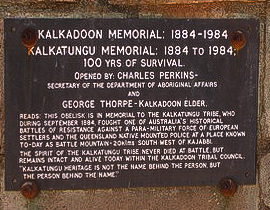

What was unexpected was coming across the small settlement of Kajabbi where, outside the Kajabbi pub, stands a cairn. This memorial in Queensland directly acknowledges the history of conflict, as one writer states, related to “the invasion of Australia by Europeans”.

Like many other plaques mounted on stone cairns, this one commemorates a centenary – 1984 was one hundred years since the slaughter of the Kalkadoon people at Battle Mountain, just southwest of this tiny speck off the beaten track. Charlie Perkins and George Thorpe, a Kalkadoon (Kalkatungka) elder, unveiled the plaque, which reads in part:

This obelisk is in memorial to the Kalkatunga tribe, who during September 1884 fought one of Australia’s historical battles of resistance against a para-military force of European settlers and the Queensland Native Mounted Police at a place known to-day as Battle Mountain 20 klms south west of Kajabbi.

This obelisk is in memorial to the Kalkatunga tribe, who during September 1884 fought one of Australia’s historical battles of resistance against a para-military force of European settlers and the Queensland Native Mounted Police at a place known to-day as Battle Mountain 20 klms south west of Kajabbi.

The spirit of the Kalkatunga tribe never died at battle but remains intact and alive today within the Kalkadoon Tribal Council.

Kalkatunga heritage is not the name behind the person, but the person behind the name.”

The Kalkadoon or Kalkatunga were considered elite warriors, but a group of early whitefella settlers, in particularly one Arthur Kennedy, took it upon themselves to kill as many of this warrior tribe as they could. Battle Mountain was the major skirmish; in all, about 900 Kalkadoon were killed in this protracted war.

The cairn is modest and I remember reading its inscription, and since I had known Charlie Perkins, whose people were from Central Australia, it was significant that he had journeyed to this remote place to unveil this plaque with a local elder. He obviously held the Kalkadoon in high regard and the timing was to celebrate the founding of the Kalkadoon Tribal Council.

It is sad to read that “native” mounted police were used to help quell the tribe. It was a common ploy to use Aboriginals from other areas to assist in helping the whitefellas. If you read accounts of skirmishes in Western Victoria in the 1840s, Aboriginal troopers were brought in from places like Tumut, hundreds of kilometres away. This usage of Aboriginal police for suppression of other Aboriginal people is a slice of Australian history which is not often ventilated.

After all it a small stone memorial in a remote hamlet on a dusty backroad, an uninviting series of dips and crests which heightened the remoteness of it all, and yet another reminder of a dark era in our history, a hundred years before when the cairn was unveiled.

Just like outside the township of Bingara in the Northern Tablelands of NSW, there is a memorial to another massacre – 50 Wirrayaraay people killed on the slopes overlooking the Myall Creek. I remember reading the last three words Ngiyani winangay genunga (we will remember them]. That atrocity more than one hundred years before. There have been more. Too many to mention here.

What prompted these memories, particularly of Kajabbi?

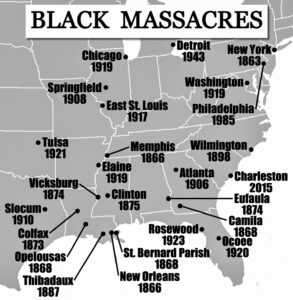

2021 was another centenary, that of the Tulsa massacre of black Americans in 1921. As if in response, the Washington Post printed a map of all the massacres of black Americans, which is reprinted. I wonder given I have been to other sites of aboriginal massacres, there is a similar map for this country, to remind us of some of the darker side of Australian history.

Maybe, Senator Stoker, it may be hidden in the archives.

Mouse Whisper

My cousin, Conte Topo has a piccolino aversion to us English speakers, who think that “simpatico” means sympathetic, a bit upper case pretentious, but unfortunately for those who like to dabble in using foreign words simpatico means “nice” not “sympathetic”. The Italian word for “sympathetic” is “comprensivo”.

In contrast, saying the obvious, the Italian word for empathetic is in fact empatico, if you wish to use such a flash word.

However, empathy and sympathy often are used interchangeably but empathy means experiencing someone else’s feelings. It requires an emotional component of really feeling what the other person is feeling. Sympathy, on the other hand, means understanding someone else’s suffering without getting under the skin. In short supply among certain Australian politicians at this time when a little sick girl is the victim.

Seriously, we forget the time saved by the modern razors, and as long as one does not use the same one more than 24 times, then it gives the facies a very close approximation to a member of human race, unlike those who bury their jaws in home grown hedges.

Seriously, we forget the time saved by the modern razors, and as long as one does not use the same one more than 24 times, then it gives the facies a very close approximation to a member of human race, unlike those who bury their jaws in home grown hedges.

I have one advantage. I have my marbles and I can look back over the past 20 years during which Treasury has put out a number of papers on this matter of ageing and the workforce – for what effect?

I have one advantage. I have my marbles and I can look back over the past 20 years during which Treasury has put out a number of papers on this matter of ageing and the workforce – for what effect?