My elder son is called Paul.

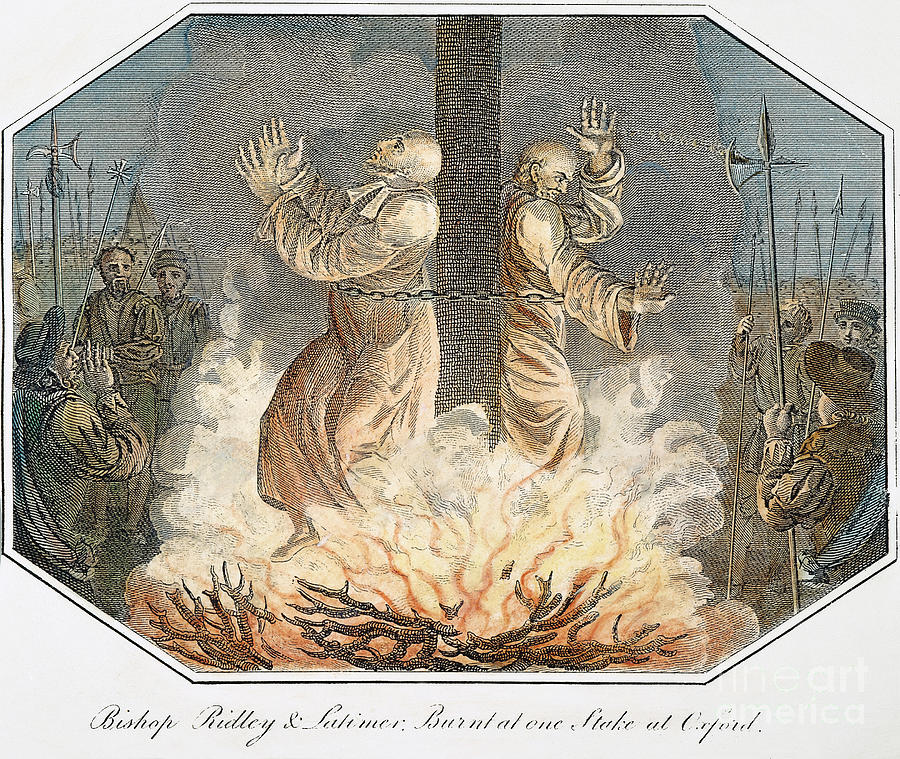

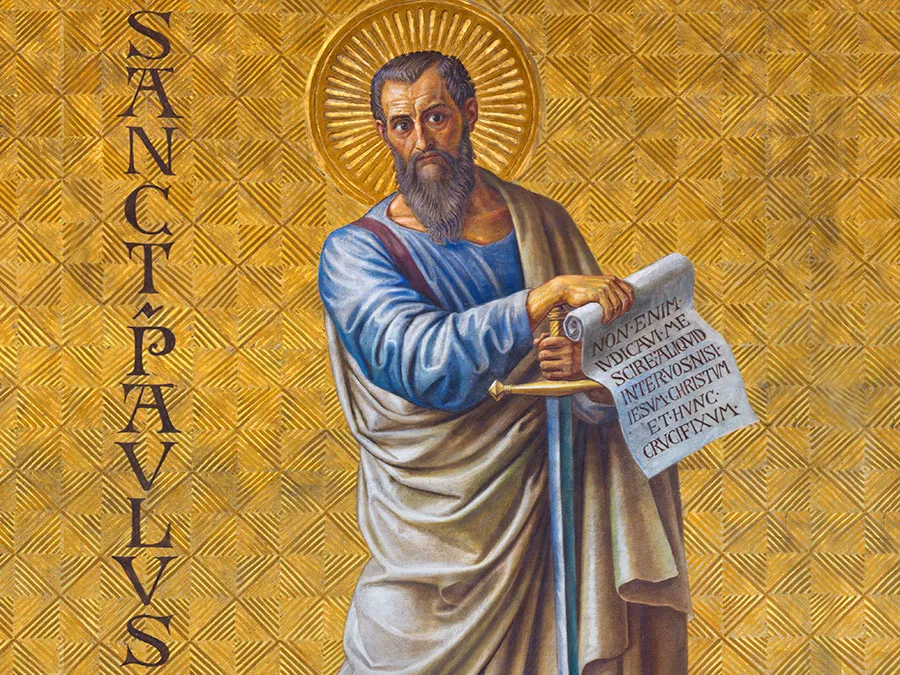

He was named after St Paul. It caused some consternation on one side of the family. Where did that name come from? “Bit Catholic” was one typical comment. Belying this comment, in Sydney there are 10 Anglican St Paul’s in addition to the Anglican St Paul’s College at the University of Sydney and only three Roman Catholic St Paul’s. In addition, there are two Lutheran Churches of that name, and shared names with St Anthony in the Coptic Church and with St Peter in the Russian Orthodox Church. Thus, recognition of St Paul is eclectic, but strongly Anglican in the Diocese of Sydney. I’m sure he would be bemused about the naming rights.

To me, St Paul was integral to the propagation of the Christian faith – the original missionary. But he is also the traditional convert who become far more wedded to the Christian cause as he did because of the fateful episode that the then Saul, a violent Anti-Christian, had that one day on the road to Damascus. I recognise that converts are often weird and fanatical but driven. In St Paul’s case, his conversion was so completely a positive event for the Church which his subsequent actions confirmed. Yet Paul did not work alone. He had supportive people by his side, for instance, Barnabas and Silas, when he made his three major tours through the Mediterranean countries. Even St Luke was present to witness his travels. St Paul attests to that in his second letter to Timothy, where Luke seems to be Paul’s only companion.

He was “a bloke” – so far from some of the modern Church ministers of religion, where raiment and the arcane trumps everything. No, he would have eschewed such frippery, despite him being painted as some balding bearded man in flowing robes. He was the archetype worker priest. He was plainspoken and yet some of his words have been so often repeated that their force is lost as a cliché.

How many times has “Through a glass darkly” been quoted; but what an image such words provoke!

St Paul was undoubtedly authoritarian – always telling the people to whom he wrote his letters what to do – probably inciting dread in the early Christian community. “Paul is coming next month. We better clean the house.”

St Paul was undoubtedly authoritarian – always telling the people to whom he wrote his letters what to do – probably inciting dread in the early Christian community. “Paul is coming next month. We better clean the house.”

He was a misogynist, but in his defence, it reflected the mores current at the time. In other words, he was not some alien person, who floated round the Mediterranean as some ethereal figure without sin.

That was the great quality of this Man – a person driven by a desire to change the world by word not sword. He projected a powerful message; and as I have always said I define my own ideal companion as a person whom I can trust but not necessarily a person who will always agree with me. Those I suspect, because if one can be as disagreeable as St Paul was on occasion, one must generate animosity even if, as can be detected in the Pauline writing, there is compassion underpinning his interpersonal relationships.

My reaction to this restless man is not unique. Other authors have noted his missionary zeal. Essentially these words in his Letter to the Philippians reveal a man, who has a firm moral code, to which he can be called to account.

Finally, brethren whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there to be any praise, think on these things.

Preceding this call for meditation are those words which have become the conventional benediction for many Christians.

And the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.

And that about says it all, except to mention that recently I prayed to St Paul for his intervention, and my prayers were answered. I have always found comfort in the above words which I whispered to myself on this occasion.

I Must Report

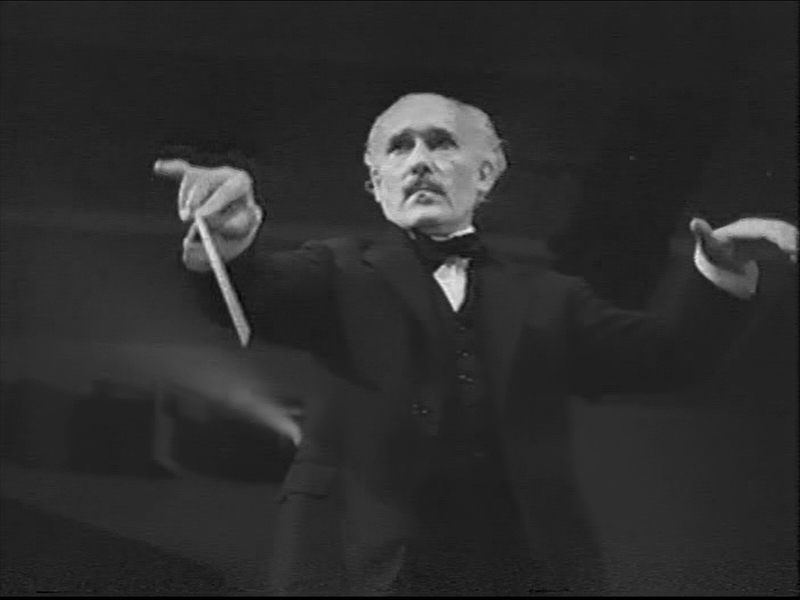

My grandfather may have described himself as a mercer rather than working in schmutter aka “the rag trade”. Notwithstanding one must call it as it is – a man in a bowler hat, detachable wing collar, handmade shirts and suit, bow tie, waistcoat with fob watch and of course spats. (Memoirs of a watcher over a Toorak stuccoed stone fence)

There are two meals that stick in my memory. Given that I have regularly devoted parts of my blog to personal observation, I thought it important for me for me to write up these two meals. They did not occur overlooking the sea or high on mountain tops; nor were these meals in elegant places with silver service and the light glinting on crystal glasses.

The first was sometime in the 1940s when there was still rationing in place. As I have written about my father’s nomadic need to travel before, once he had a car, he would often try to get away for a weekend with my mother and myself. There were no motels and therefore we depended on the availability of local hotels to have a bed. Towns had the Railway Hotel and the Commercial hotels to reflect where they were built and who inhabited them during the week. And Strathmerton did not disappoint – there was a low-slung Railway Hotel. Strathmerton was a small dairying town just south of the Murray River on the edge of the Goulburn Valley.

Remember, this was a time before credit cards, and payment was restricted to cash or cheque.

Now why do I remember this place. In the morning, the breakfast was something I had never experienced: sausages, steak and eggs, and the bacon. I still can picture those rashers of bacon. The toast was thick, warm and buttery.

This was a time when rationing of some food items was still in place, meat and tea. Eggs, milk and particularly butter were in restricted supply – sugar was removed from rationing in 1947. I had only experienced brown sugar, so white sugar was a novelty. Chocolate was non-existent, except in Laxettes.

This was a time when rationing of some food items was still in place, meat and tea. Eggs, milk and particularly butter were in restricted supply – sugar was removed from rationing in 1947. I had only experienced brown sugar, so white sugar was a novelty. Chocolate was non-existent, except in Laxettes.

None of these restrictions meant much because, until I was six, I had never lived in a country not at war. When I stayed in the country then with my aunts there were eggs and milk. I did not like milk anyway. But eggs … and Marmite; that was something else.

This breakfast was so different – a full on delicious Australian breakfast. I have always enjoyed big breakfasts since, but unfortunately in growing older self-rationing becomes de rigeur.

The second memorable meal came in the second year after graduation. It was the first time we had a car. I was married and our first child was on his way; yet we had no car. I had a job at Geelong Hospital, but my wife was working as a post-graduate research scholar at the University of Melbourne. My mate, Don Edgar had been recently ordained and he had a locum posting in Tallangatta in North-east Victoria.

We had not seen him for a while, and he invited us up to stay with him. But we could not have chosen a worse night to drive. It was a time when a car may have had a heater but was not air conditioned, where the car did not have the safety features of the modern cars, and the Hume Highway was still mostly two-lane. The weather was bitterly cold, it was winter, and at times we encountered sleet.

I remember bringing a bottle of Moyston claret to drink with Don if and when we got there. In a time before mobile phones, and a disinclination to venture out into the weather to ring him from a phone box, we pressed on.

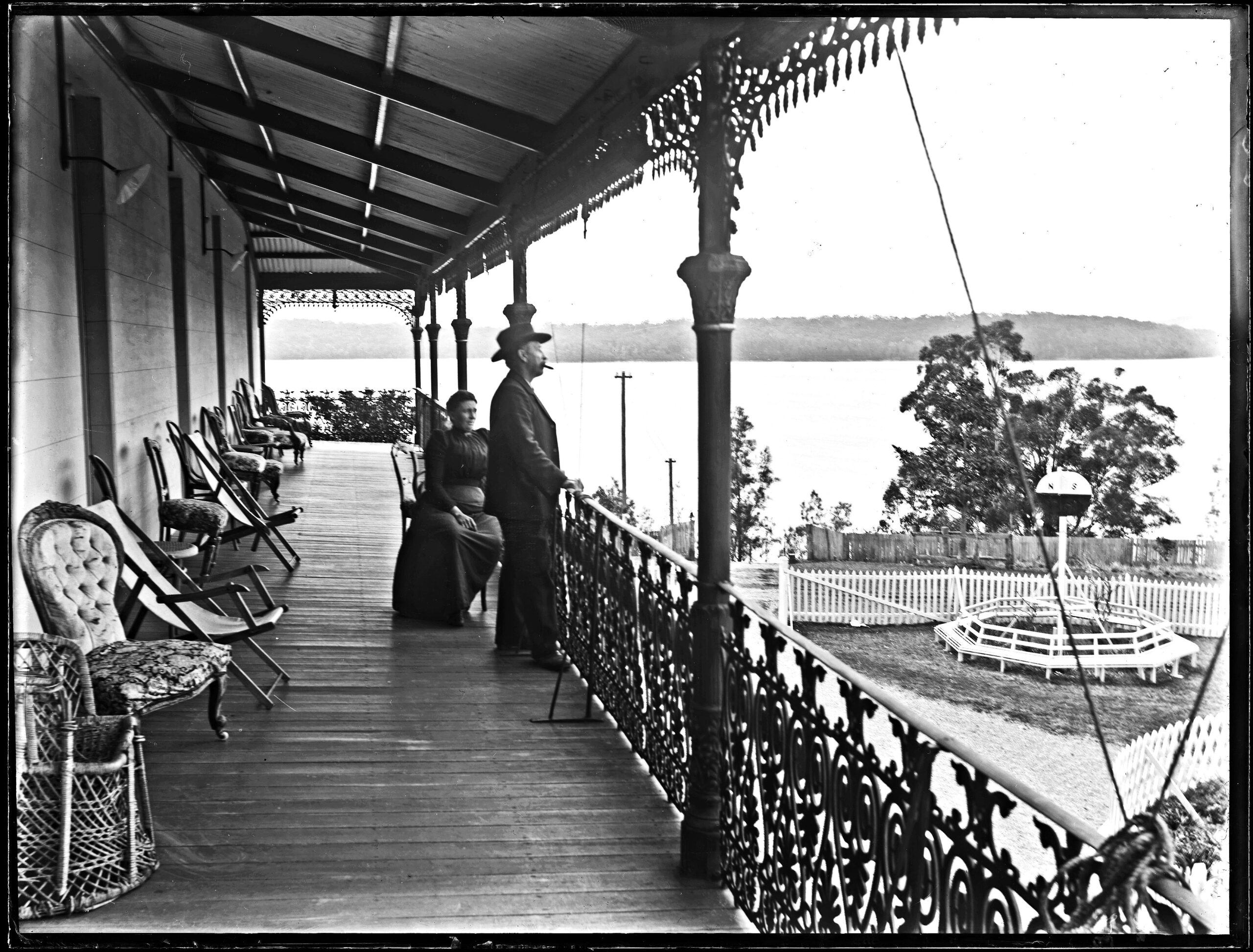

Tallangatta is a village on the shores of the Hume Weir, which had been rebuilt once the original township was sacrificed to be swallowed when the Murray River was dammed.

Once we arrived in Tallangatta it took us time to find where Don was living. Eventually, we saw the light in the window, and there was Don at the door, appropriately rugged up.

He ushered us inside, where he had built a roaring fire. The residence was basic but coming in after such a stressful drive it was a palace. The claret was warmed; the soup was robust, and the bread rolls were fine. This was almost biblical, but fish was not on the menu.

A Forgotten Observer

They were familiar not only with the grass seed they so laboriously gathered and ground into flour, but with many bulbs and herbs and underground nuts and tubers also, the native carrot and native onion, the edible yam, which is so like our floury potatoes and a much sought-after food all over the continent. The quandong, too, sometimes called the wild peach, which is good eating when raw and makes a tasty jam – how easily could a tribe have planted practically unlimited number of such fruit-trees! Yet these things they never once thought of growing and cultivating during all the thousands of years they have been struggling for life in this country. And yet they carefully explain to their baby daughters all about the yam-vine from its “beginning” to its “end”, the soils the different varieties grow in, and the conditions and seasons necessary for its growth. They even explain that a few must always be left, so that with the next rain others may grow up. Yet apparently, they have never thought of planting one.

In the coastal and more favoured areas of the continent, if they had thought of such a thing they might have said, “Everything grows in plenty for us here, in a good season anyway, then why should we toil to grow it?” But over the far greater area of the continent, with its recurring harsh times, that they never thought to improve their food supply by growing edible seeds and plants and fruits is a puzzle in the progress of human life.

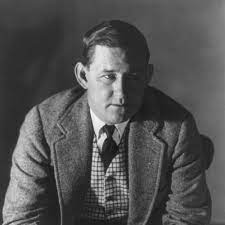

Ion Idriess was a prolific author, writing 50 novels about this country of ours. He has lost the popularity he once had, but for a man born in Sydney in 1889 and dying 90 years later in Sydney in the intervening years he was very busy. There was an extraordinary litany of achievements through various occupations – opal, tin, gold miner, buffalo and dingo shooter, shearer, boundary rider – in diverse parts of Northern Australia. He encountered many Indigenous people, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

His perspective in the above has, to my mind, never been introduced into the confused debate of whether the Aboriginal people ever embraced the agricultural revolution.

His writing at times makes one react as if he was scratching his fingernail across a blackboard. The use of “Stone Age” as a description is not acceptable, because clearly the Aboriginal people are not. The use of inappropriate language in one context does not destroy the validity of his interpretation of some of his observations. In the face of these observations what sophistry would Bruce Pascoe use to justify his thesis? What I have found irritating in all this debate, given all the literature available, is how much has been ignored, such as that of Idriess.

Idriess, because of his times and his language in relation to Aboriginal contact, might jar. Nevertheless he had a clear eye, and in days before the taboos were well articulated said he was able to “bribe a ‘witch doctor’ ” into showing his sacred objects. Again, the Aboriginal “witch doctor” may have double-crossed him about the nature of what he revealed, but the observation may have been just as valid.

It is just that I once was given the privilege of seeing sacred objects, which only men are allowed to see. His observations did not tally with mine. However, the diversity of these individual tribes should never be underestimated, and every time I look at my collection of paintings and other artefacts, it just reinforces the diversity among these Aboriginal mobs. Idriess travelled extensively and that is why his descriptions ring true. He was an observer, admittedly culturally insensitive, but nevertheless historically valuable in being able to describe situations that now are hidden by cultural taboos, whether confected or not.

One of Idriess’ strengths was that he effortlessly mingled with Aboriginal people, but never “went native”. Like me, he did not have the genes which had been coursing through Aboriginal people for thousands of years. I retain the ultimate regard for the heritage of Aboriginal people.

If there were to be an honest appraisal of the actual achievements not the constant blame as if it were totally one-sided; the persistent talk without action (so-called “conversations” in different exotically attractive venues across the continent, also a form of expensive, diversional therapy for whitefellas able to afford the entry and travel costs or paid courtesy of the government), then I would without question vote “Yes”.

There is so much humbug floating around.

Try a “conversation” in the Tanami desert in January, Prime Minister.

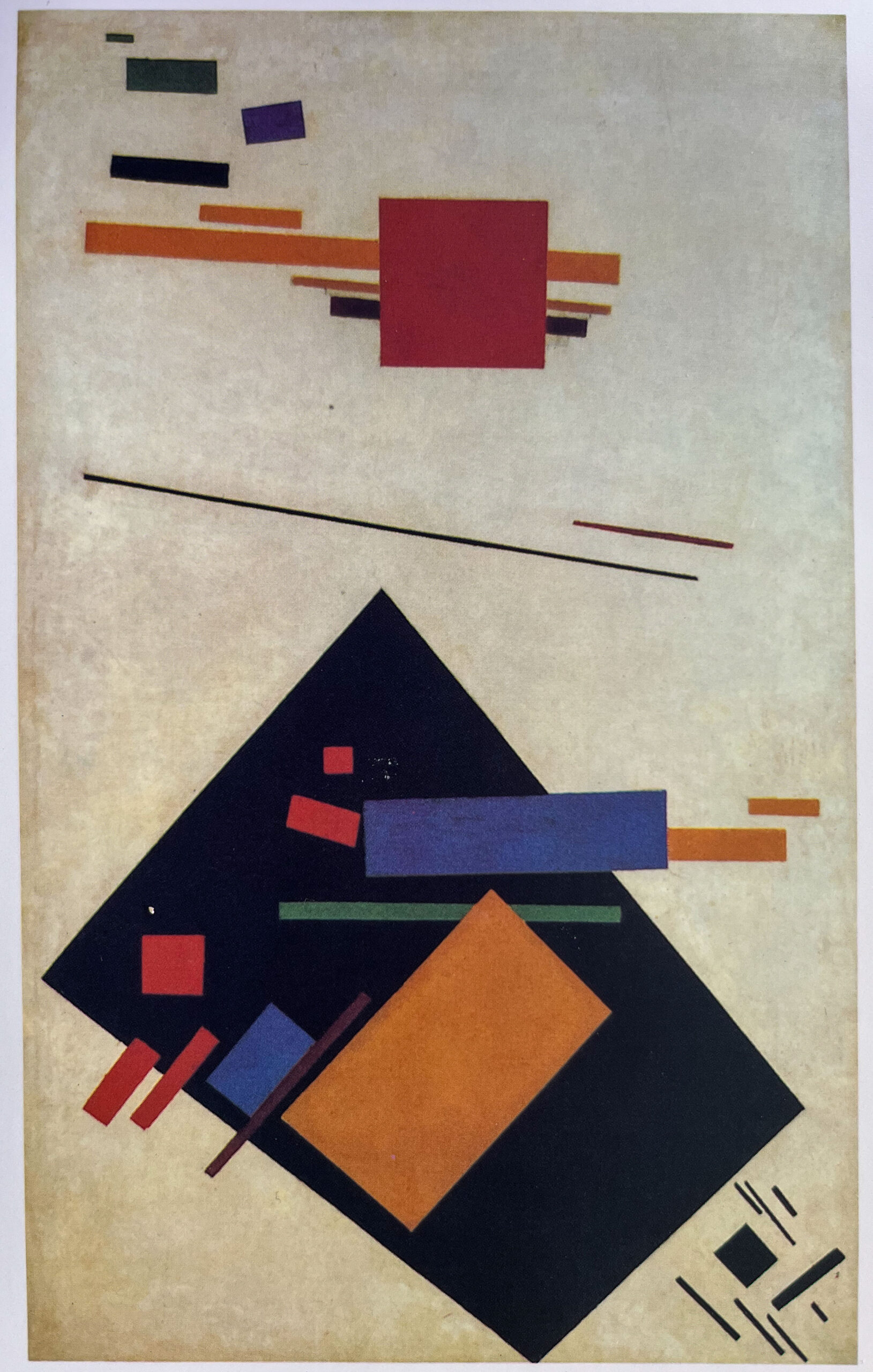

Malevich – Remarkable Painter

The Athletes also concerns the artist’s own metaphysics, which are quite distinct from that of the stablished church. He has erased all particular detail in order to bring to the fore his vision of humanity’s connection to the cosmos …The removal of facial features and the lowering and flattening of the horizon graphically emphasise the figures’ tenuous connection with the earth. Their feet on the coloured ground, their heads in the infinite white heavens – their half-white heads – all express the dualistic nature of natural beings and their evolving destiny.

I was sorry that we were unable to visit the Vermeer exhibition this year in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Vermeer, together with Magritte and Malevich, are the three painters whose exhibitions, in normal circumstances, I would have made every effort to travel anywhere to see.

We did so in 1998 for the exhibition in Brussels to celebrate the centenary of Magritte’s birth. I have written about the hoops we had to jump through to gain entry into that exhibition. This escapade has stuck in my memory; it was a good story, especially as it ended up in the “happily ever after” box.

But what of Malevich, the third of “my must see” painters?

I stare hard at the figurine of one of the Athletes in the painting by Kazimir Malevich. I purchased the figurine as a memento of the Malevich exhibition. It was the one with half the head coloured red the other side white. The rest of the figurine is a mixture of red and black. It doesn’t look like an Athlete, but I read the explanation, with which I headed this piece. I also have a coffee table book which shows most of his paintings, as well as a set of Malevich postcards and a large poster titled The Carpenter, which was painted and reflects very much the style he used in The Athletes.

I stare hard at the figurine of one of the Athletes in the painting by Kazimir Malevich. I purchased the figurine as a memento of the Malevich exhibition. It was the one with half the head coloured red the other side white. The rest of the figurine is a mixture of red and black. It doesn’t look like an Athlete, but I read the explanation, with which I headed this piece. I also have a coffee table book which shows most of his paintings, as well as a set of Malevich postcards and a large poster titled The Carpenter, which was painted and reflects very much the style he used in The Athletes.

Kazimir Malevich, the man born near Kiev in 1878, spent most of his life in Russia. His professional career was counterpointed by the 1917 October Revolution and the growth of the Soviet Union. He died in the then Leningrad in 1935. Only on two occasions did he leave Russia, having been given permission to go to Poland and Germany in the 20s. Most of his works therefore are retained in Russian Galleries, but there was an exhibition of his paintings a decade ago at the Tate Gallery in London.

He was the central figure in the Supremacist movement and there is a great force in his paintings – notably in his originality in style. He is the one painter, whose work I could gaze at for hours. For most galleries I just breeze around absorbing image after image without stopping for long in front of each work. Yes, I admit Guernica, Picasso’s painting makes me want to sit and have a longer look. Otherwise, Picasso does not provoke the same level of interest as Malevich; Picasso had this great facility to dash off a figure with an almost impeccable facility, but they do not connect emotionally.

But Malevich, with his ability to break form down to component and colour, appropriately and deftly lays a beautiful tableau. Even the definition of the principles of Suprematism to reject any form of realism and paint simple shapes such as the circle, square and triangles forces one to recast your view of the world. They also used these shapes as vessels to explain and communicate themselves to the public or the viewer without any use of words or typography. There was limited use of colour in the palette with only basic colours such as red, yellow, blue and green, in addition to white and black.

This colour minimalism is shown by a series of diagrammatic paintings, with anonymous numbering of most of them. What I find fascinating is they seem to be architectural drawings if viewed casually, perfectly outlined rectangles, circles, squares – the architect of the cosmos. The juxtaposition of the components seems to be in harmony; I frankly don’t know why and thus if I try to articulate what they mean I’ll end up in a tangle of words. There is one of these Supremacist works which he links to an aeroplane taking off. The reference point to this are several red lines – he would deny that the red line was the horizon, just a guide to his black and yellow rectangles and oblongs, the plane about to fly off the page.

The solid black painting is the signature of the Supremacist movement – just a pure Black Square. As though in a dark place we are seeing a lunar eclipse at the time when the Moon is closest to the earth (perigee), but paradoxically The Black Square is boxed in by a frame, and it is always hung in a corner of the gallery where normally in the Russian household an icon is hung. I can see what Malevich is trying to do, but that painting is easily mocked by others, including the Australian painter who replicated the Black Square by inserting a combination lock into his version of the Black Square. It brought contemplation of this Malevich work back to Earth.

On Malevich’s gravestone there is a Black Square, with a generous white concrete border.

Malevich went through post-impressionist, cubism, fauvism phases. After his Supremacist period, he reverted to folk artist primitivism, which persisted up to his death. Given how uncertain life was under Stalin, in a period where purges had continued that Russian propensity for pogroms, Malevich may have gone back to folk art as a Survival phase, but he did not live to the Great Terror of 1937. Yet one of the enigmas surrounding Malevich is his sudden cessation of Supremacist painting and reversion to folk art. Why? Perhaps he could not progress his ideas any further.

In the end, if you asked why I so am attracted to Malevich that once I was prepared to travel across the world to see a retrospective, it is his unique representation of the level of affinity and appreciation of what are essentially spatial juxtapositions, so clinical and technical; yet so original … and so difficult to articulate.

Mouse Whisper

Wrestling with concept of Suprematism?

A plane of painted colour hung on a white sheet of canvas imparts a strong sensation of space directly to our consciousness. It transports me into an endless emptiness, where all around you sense the creative nodes of the Universe.” – Kazimir Malevich.

To be read in conjunction with “Untitled (Suprematist Painting) painted in 1915 now hanging in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

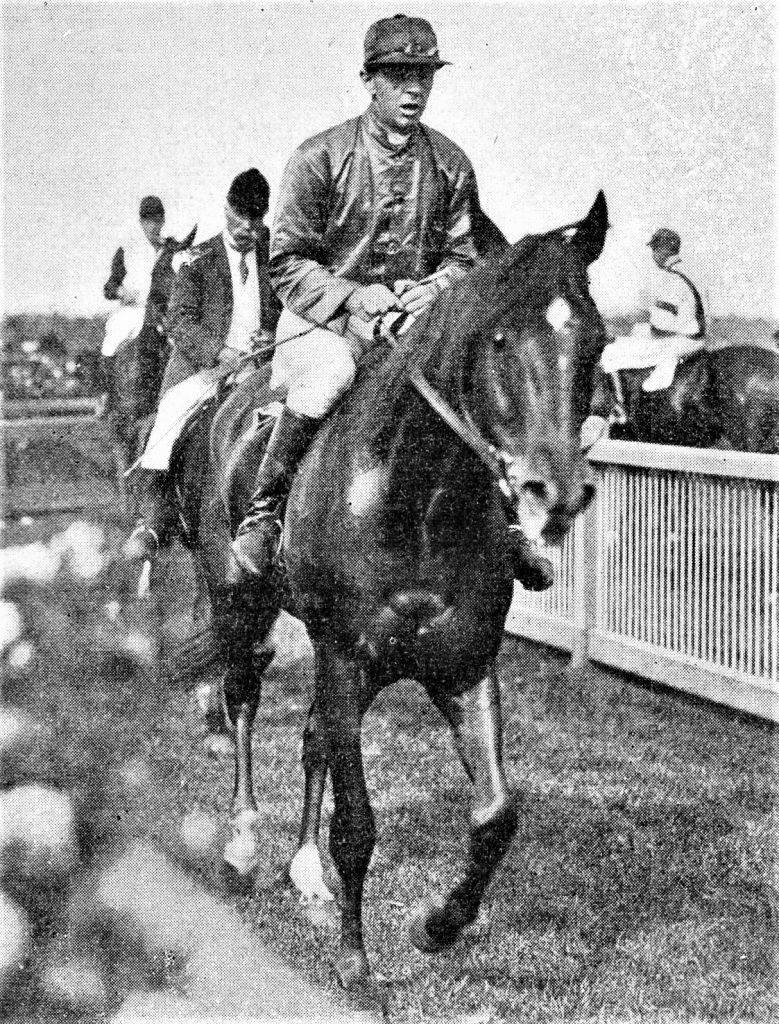

What was pony racing? For some the name conjures images of children riding Shetland ponies in “hay-bale” hurdle races at agricultural shows. This is totally misleading; in Australia, pony racing was the name given to a sport conducted at racecourses that raced outside Australian Jockey Club and Victoria Racing Club jurisdictions and were so popular they were a constant thorn in the side to these clubs of the establishment. It was racing’s pioneering equivalent of the “Super-league” and World Series Cricket schisms. Most races at “pony” meetings were in fact contested by fully-grown thoroughbreds.

What was pony racing? For some the name conjures images of children riding Shetland ponies in “hay-bale” hurdle races at agricultural shows. This is totally misleading; in Australia, pony racing was the name given to a sport conducted at racecourses that raced outside Australian Jockey Club and Victoria Racing Club jurisdictions and were so popular they were a constant thorn in the side to these clubs of the establishment. It was racing’s pioneering equivalent of the “Super-league” and World Series Cricket schisms. Most races at “pony” meetings were in fact contested by fully-grown thoroughbreds. Given that the Government was faced down by the “dishlicker” lobby over the suggestion that dog racing had seen its day, there is a latent underground force dedicated, irrespective of the popularity, to keeping all the sports upon which a wager could be laid on the outcome of animal races. Yet what is the point of having a dog track almost in the heart of the city, when that track attracts few paying customers – in fact an average of 120 people per race meeting has been quoted – but the defence is that it generates $50m in revenue a year. This of course begs the questions of where is evidence of the $50m, and why not simply computerise all the dog racing – computerised dog racing was run in TABs years ago. The defenders talk about people who will be put out of work, without any evidence of how many would be affected. The reality is that there is an abundance of greyhounds that need homes.

Given that the Government was faced down by the “dishlicker” lobby over the suggestion that dog racing had seen its day, there is a latent underground force dedicated, irrespective of the popularity, to keeping all the sports upon which a wager could be laid on the outcome of animal races. Yet what is the point of having a dog track almost in the heart of the city, when that track attracts few paying customers – in fact an average of 120 people per race meeting has been quoted – but the defence is that it generates $50m in revenue a year. This of course begs the questions of where is evidence of the $50m, and why not simply computerise all the dog racing – computerised dog racing was run in TABs years ago. The defenders talk about people who will be put out of work, without any evidence of how many would be affected. The reality is that there is an abundance of greyhounds that need homes.

During this last week, the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation in South Australia has the Federal Court ruling in its favour in relation to a nuclear waste dump. The Federal Education Minister has opened the universities to essentially positive affirmation for Indigenous people. Then Michael Mansell, whose playbook is that of protest, comes out with a reasoned argument to call off the referendum all together and start negotiating a treaty. At no stage has there been any impediment because Aboriginal rights have not been incorporated into the Constitution, and with all respects, what happened this past week epitomises policy development.

During this last week, the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation in South Australia has the Federal Court ruling in its favour in relation to a nuclear waste dump. The Federal Education Minister has opened the universities to essentially positive affirmation for Indigenous people. Then Michael Mansell, whose playbook is that of protest, comes out with a reasoned argument to call off the referendum all together and start negotiating a treaty. At no stage has there been any impediment because Aboriginal rights have not been incorporated into the Constitution, and with all respects, what happened this past week epitomises policy development. The money has provided investment in a sawmill, and the ABC reported that it had been productive; yet on the day the ABC reporters visited, there was only one worker on site, the rest were on the local version of “sorry business”. So, what’s new? To think that these Aboriginal mobs having had the chance to invest the royalties are talking about going back on welfare mocks the very essence of the “Yes” case.

The money has provided investment in a sawmill, and the ABC reported that it had been productive; yet on the day the ABC reporters visited, there was only one worker on site, the rest were on the local version of “sorry business”. So, what’s new? To think that these Aboriginal mobs having had the chance to invest the royalties are talking about going back on welfare mocks the very essence of the “Yes” case. “The multi-city model for delivering Victoria 2026 was an approach proposed by the Victorian Government, in accordance with strategic roadmap of the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) … beyond this, the Victorian Government wilfully ignored recommendations to move events to purpose-built stadia in Melbourne and in fact remained wedded to proceeding with expensive temporary venues in regional Victoria.”

“The multi-city model for delivering Victoria 2026 was an approach proposed by the Victorian Government, in accordance with strategic roadmap of the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) … beyond this, the Victorian Government wilfully ignored recommendations to move events to purpose-built stadia in Melbourne and in fact remained wedded to proceeding with expensive temporary venues in regional Victoria.”

I was reminded of the first by this long article in The Guardian about borscht. I advisedly spell it the Yiddish way because it was presented to us one Friday night at Shabbat. As I understand it, heating the food for Shabbat is not done, so when we sat down we were presented with this blood red beetroot cold soup. For those of us not used to such soup, including myself, I felt as I sipped it, my stomach immediately rejecting it and that going down was met by that coming up. I was not alone. There is no etiquette for vomiting at the dinner table, especially when presented with a signature dish. There was a certain embarrassment, but the gefilte fish attracted more positive comments. I must say that I have eaten borscht since, but always warm – not that I have a phobia about cold soup. Iced gazpacho on a hot day is a magnificent culinary antidote on such a day.

I was reminded of the first by this long article in The Guardian about borscht. I advisedly spell it the Yiddish way because it was presented to us one Friday night at Shabbat. As I understand it, heating the food for Shabbat is not done, so when we sat down we were presented with this blood red beetroot cold soup. For those of us not used to such soup, including myself, I felt as I sipped it, my stomach immediately rejecting it and that going down was met by that coming up. I was not alone. There is no etiquette for vomiting at the dinner table, especially when presented with a signature dish. There was a certain embarrassment, but the gefilte fish attracted more positive comments. I must say that I have eaten borscht since, but always warm – not that I have a phobia about cold soup. Iced gazpacho on a hot day is a magnificent culinary antidote on such a day. The second disastrous introduction was to the avocado. One night, we had been invited to a dinner party. It was sometime in the early 1960s. The hostess produced this unfamiliar green fruit, which vaguely resembled a pebbled-skin pear. However, nobody had told her that they had to be ripe to eat. Hence, we struggled with the yellowish flesh surrounding the central seed. Unripe avocado flesh, as we found out, was like concrete, and after hacking pieces of this flesh, it proved completely inedible. Nobody had thought to read anything about the fact that avocados had to ripen – and as we were already well lubricated, the avocados were swiftly destined for the rubbish bin.

The second disastrous introduction was to the avocado. One night, we had been invited to a dinner party. It was sometime in the early 1960s. The hostess produced this unfamiliar green fruit, which vaguely resembled a pebbled-skin pear. However, nobody had told her that they had to be ripe to eat. Hence, we struggled with the yellowish flesh surrounding the central seed. Unripe avocado flesh, as we found out, was like concrete, and after hacking pieces of this flesh, it proved completely inedible. Nobody had thought to read anything about the fact that avocados had to ripen – and as we were already well lubricated, the avocados were swiftly destined for the rubbish bin. The third disastrous introduction was to the persimmon. There are two varieties of persimmon – those that are astringent when not perfectly ripe and those which are not. This time the particular hostess proudly presented us with persimmons as a treat at the end of the meal. Unfortunately, they were the astringent types, and I referred to my mouth after eating a sliver as being like having an Axminster carpet lining my mouth, so great was the astringency.

The third disastrous introduction was to the persimmon. There are two varieties of persimmon – those that are astringent when not perfectly ripe and those which are not. This time the particular hostess proudly presented us with persimmons as a treat at the end of the meal. Unfortunately, they were the astringent types, and I referred to my mouth after eating a sliver as being like having an Axminster carpet lining my mouth, so great was the astringency.

Kingaroy is the peanut growing centre of Australia. The terracotta soil is apparently excellent for the cultivation of the underground peanut, and my wife in a spirit of horticultural patriotism only buys Kingaroy peanuts.

Kingaroy is the peanut growing centre of Australia. The terracotta soil is apparently excellent for the cultivation of the underground peanut, and my wife in a spirit of horticultural patriotism only buys Kingaroy peanuts. Bunya Pines grow up to 50m tall, and in summer are potentially dangerous, because they have this unpredictable knack of ‘bombing’ with their nut. These nuts can weigh up to 10 kgs, so being hit with one of these is potentially lethal if one is unfortunate enough to be standing under that Bunya. Despite the dire warning, it is difficult to find any record of a person who has actually died by Bunya cone.

Bunya Pines grow up to 50m tall, and in summer are potentially dangerous, because they have this unpredictable knack of ‘bombing’ with their nut. These nuts can weigh up to 10 kgs, so being hit with one of these is potentially lethal if one is unfortunate enough to be standing under that Bunya. Despite the dire warning, it is difficult to find any record of a person who has actually died by Bunya cone.

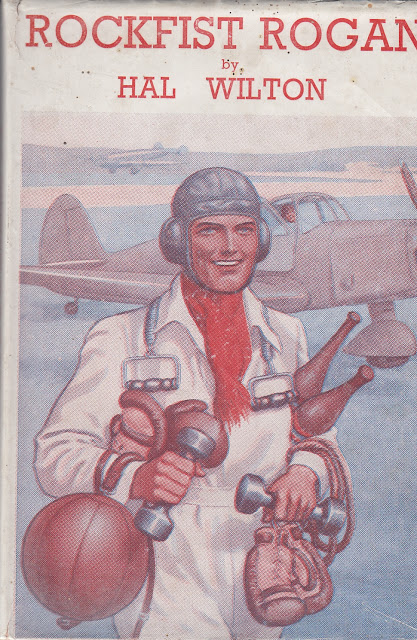

I remember buying my first Champion, an English “boy story paper” at the newsagency at Flinders Street station, and my mother relented. Then for some years I regaled myself with stories about Rockfist Rogan, a World War II air ace, Colwyn Dane, a “tec”, Danny of the Dazzlers, a football team which seemed to be modelled on Arsenal, with feeder teams such as the Glimmers to construct a hierarchy of teams based on luminosity. There was the obligatory school hero, Ginger Nutt, “the boy who took the Biscuit”.

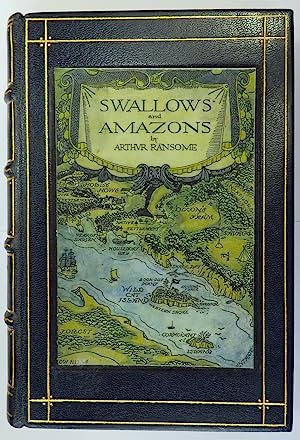

I remember buying my first Champion, an English “boy story paper” at the newsagency at Flinders Street station, and my mother relented. Then for some years I regaled myself with stories about Rockfist Rogan, a World War II air ace, Colwyn Dane, a “tec”, Danny of the Dazzlers, a football team which seemed to be modelled on Arsenal, with feeder teams such as the Glimmers to construct a hierarchy of teams based on luminosity. There was the obligatory school hero, Ginger Nutt, “the boy who took the Biscuit”. There were two streams of books that were popular. One was the Biggles books, with his sidekicks, Algy, Worrall and Gimlet. The others were the Swallows and Amazons series of Arthur Ransome, children’s adventures mainly on Cumbria lakes and the Norfolk Broads.

There were two streams of books that were popular. One was the Biggles books, with his sidekicks, Algy, Worrall and Gimlet. The others were the Swallows and Amazons series of Arthur Ransome, children’s adventures mainly on Cumbria lakes and the Norfolk Broads.

Thus, this area has always fascinated me – the more so when I was said to resemble Elton John. I remember a time when Elton John was touring Australia and sustained a leg injury which put him in a wheelchair. One of my associates at the time said: “Put Jack in a wheelchair with a cowboy hat and nightclubs, here we come!”

Thus, this area has always fascinated me – the more so when I was said to resemble Elton John. I remember a time when Elton John was touring Australia and sustained a leg injury which put him in a wheelchair. One of my associates at the time said: “Put Jack in a wheelchair with a cowboy hat and nightclubs, here we come!”

The sand dollar is also known as the Holy Ghost Shell, essentially the skeleton of a sea urchin. In South Carolina there are stiff penalties if one removes them live, but when they die, they are left as bleached calciferous discs. They are not uncommon, but as they tend to be fragile, by the time they get to the beach most are cracked or chipped. I have two – one the natural remnant and the other made from base metal which I was given as a present. The shells are full of Christian symbolism relating to Jesus Christ.

The sand dollar is also known as the Holy Ghost Shell, essentially the skeleton of a sea urchin. In South Carolina there are stiff penalties if one removes them live, but when they die, they are left as bleached calciferous discs. They are not uncommon, but as they tend to be fragile, by the time they get to the beach most are cracked or chipped. I have two – one the natural remnant and the other made from base metal which I was given as a present. The shells are full of Christian symbolism relating to Jesus Christ.

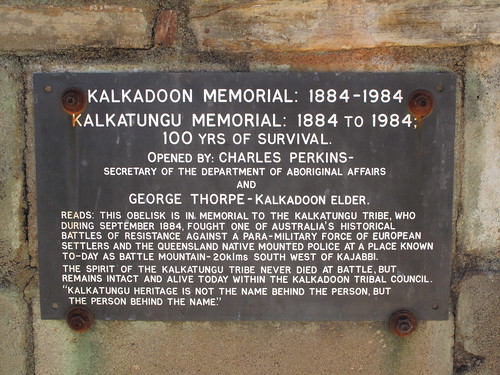

Queensland, by contrast, had a strong history of Aboriginal troopers. I remember coming back from Normanton in the Gulf Country via the back road to Cloncurry. Near the hamlet of Kajabbi, there is a cairn which was dedicated by Charlie Perkins and a Kalkadoon elder, George Thorpe, in 1984. The memorial commemorates one hundred years since the battle between Aboriginal tribes, in particular the Kalkadoon, and the native Mounted Police under Sub-Inspector Fred Urquhart. For eight years he commanded a huge swathe of Far Northern Queensland including not only the Gulf but also the whole of Cape York and Thursday Island.

Queensland, by contrast, had a strong history of Aboriginal troopers. I remember coming back from Normanton in the Gulf Country via the back road to Cloncurry. Near the hamlet of Kajabbi, there is a cairn which was dedicated by Charlie Perkins and a Kalkadoon elder, George Thorpe, in 1984. The memorial commemorates one hundred years since the battle between Aboriginal tribes, in particular the Kalkadoon, and the native Mounted Police under Sub-Inspector Fred Urquhart. For eight years he commanded a huge swathe of Far Northern Queensland including not only the Gulf but also the whole of Cape York and Thursday Island.

The opening sequence features an orange Lamborghini Miura being driven up the winding Great Bernard Pass. The pass links the Aosta Valley region of north-western Italy and the Canton of Valais in Switzerland. The opening scene features Rossano Brazzi at the wheel, fag in mouth and wearing fashionable sunglasses – Ford Mustang Renauld Spectaculars. The sunglasses were specifically designed for driving, with the curved sides to stop wind coming through.

The opening sequence features an orange Lamborghini Miura being driven up the winding Great Bernard Pass. The pass links the Aosta Valley region of north-western Italy and the Canton of Valais in Switzerland. The opening scene features Rossano Brazzi at the wheel, fag in mouth and wearing fashionable sunglasses – Ford Mustang Renauld Spectaculars. The sunglasses were specifically designed for driving, with the curved sides to stop wind coming through. Oh, what a relief. I must say the fuss surrounding this car, with its numbered chassis #3586, was surprisingly lost for 50 years after its appearance in the 1969 film. When the car reappeared, it needed restoration and now resides with its owner in Liechtenstein, with a value of about US$5m.

Oh, what a relief. I must say the fuss surrounding this car, with its numbered chassis #3586, was surprisingly lost for 50 years after its appearance in the 1969 film. When the car reappeared, it needed restoration and now resides with its owner in Liechtenstein, with a value of about US$5m. Turin is a sedate city, not the frenetic scene in what was a very entertaining film, and there is no doubt that Turin is one of those Northern Italian cities which is known, at least for a long time, by the Mini Cooper car chase through its streets, the colonnades perfect for the car stunts. The classic pursuit through the sewers was not actually filmed in Turin but in England. Obviously in the traffic gridlock scenes, the Torinese seemed to be enjoying themselves; but even if you paid me, I would not have been one of that crowd. I totally unspool if caught in traffic jams, let alone that crazy gridlock with a crescendo of car horns as depicted in the film.

Turin is a sedate city, not the frenetic scene in what was a very entertaining film, and there is no doubt that Turin is one of those Northern Italian cities which is known, at least for a long time, by the Mini Cooper car chase through its streets, the colonnades perfect for the car stunts. The classic pursuit through the sewers was not actually filmed in Turin but in England. Obviously in the traffic gridlock scenes, the Torinese seemed to be enjoying themselves; but even if you paid me, I would not have been one of that crowd. I totally unspool if caught in traffic jams, let alone that crazy gridlock with a crescendo of car horns as depicted in the film.

After all, Uluru is not her Land. It is Anangu, but conveniently a tourist resort able to be isolated in beautiful photographic layouts. It is also where the Southern skies can be visualised with minimal light pollution.

After all, Uluru is not her Land. It is Anangu, but conveniently a tourist resort able to be isolated in beautiful photographic layouts. It is also where the Southern skies can be visualised with minimal light pollution.

And my lasting impression? Workers eating this green food with chips and mayonnaise. This is palint ‘n groen – eels served with a green sauce made with fresh river herbs and wild leaf vegetables, chervil, sorrel, spinach, watercress and wild garlic leaves. Tasted it – not too bad.

And my lasting impression? Workers eating this green food with chips and mayonnaise. This is palint ‘n groen – eels served with a green sauce made with fresh river herbs and wild leaf vegetables, chervil, sorrel, spinach, watercress and wild garlic leaves. Tasted it – not too bad.

Grievances are met with counter grievance. As someone said, looking at the Aboriginal flag and the Australian flag flying alongside each other on the Harbour Bridge, why? The same person sees the Aboriginal flag as a sign of division and the Australian flag as an embarrassing relic – both to be replaced by a single flag for everyone in the country. Personally, I believe the Aboriginal flag should be the Australian flag rather than the colonial relic. But to me whose ancestors have occupied the country as part of the Celtic diaspora, the Eureka flag flown first by the Ballarat miners during their 1854 insurrection also epitomises that Australia is my Land – and let nobody forget that. I too have a Voice. That is precious privilege of Democracy.

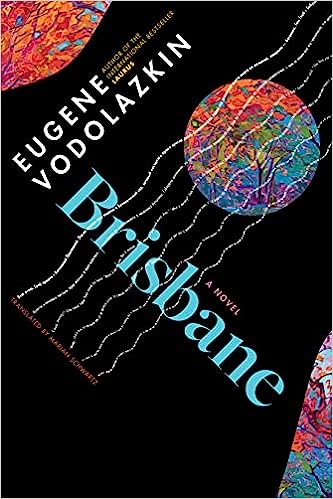

Grievances are met with counter grievance. As someone said, looking at the Aboriginal flag and the Australian flag flying alongside each other on the Harbour Bridge, why? The same person sees the Aboriginal flag as a sign of division and the Australian flag as an embarrassing relic – both to be replaced by a single flag for everyone in the country. Personally, I believe the Aboriginal flag should be the Australian flag rather than the colonial relic. But to me whose ancestors have occupied the country as part of the Celtic diaspora, the Eureka flag flown first by the Ballarat miners during their 1854 insurrection also epitomises that Australia is my Land – and let nobody forget that. I too have a Voice. That is precious privilege of Democracy. I was thumbing through a recent issue of the NYRB and came across a review by the above author. The book was entitled Brisbane. Given that Brisbane and Russian literature are not ready companions, I read the review. On reading this, it seemed to be just an extension of my perspective of Russian literature, telling the Russian story where Death is an ever-present metronome of the various degrees of misery and cruelty which pockmark the whole literary Russian Treasury of the mysteries of life. These mysteries have always been palpable in the Russian Orthodox liturgy, and in its extraordinary church music, where it soars from the depths to the heights. Terra ad caelium.

I was thumbing through a recent issue of the NYRB and came across a review by the above author. The book was entitled Brisbane. Given that Brisbane and Russian literature are not ready companions, I read the review. On reading this, it seemed to be just an extension of my perspective of Russian literature, telling the Russian story where Death is an ever-present metronome of the various degrees of misery and cruelty which pockmark the whole literary Russian Treasury of the mysteries of life. These mysteries have always been palpable in the Russian Orthodox liturgy, and in its extraordinary church music, where it soars from the depths to the heights. Terra ad caelium.

Along the roads, laurel, viburnum and alder, great ferns and wildflowers delighted the traveler’s eye through much of the year. Even in winter the roadsides were places of beauty, where countless birds came to feed on the berries and on the seed heads of the dried weeds rising above the snow. The countryside was, in fact, famous for the abundance and variety of its bird life, and when the flood of migrants was pouring through in spring and fall people traveled from great distances to observe them.

Along the roads, laurel, viburnum and alder, great ferns and wildflowers delighted the traveler’s eye through much of the year. Even in winter the roadsides were places of beauty, where countless birds came to feed on the berries and on the seed heads of the dried weeds rising above the snow. The countryside was, in fact, famous for the abundance and variety of its bird life, and when the flood of migrants was pouring through in spring and fall people traveled from great distances to observe them.