As I am putting this blog together, it is Sunday, and I am reminded that it is September 11. On the morning of September 12 in 2001, for some reason I woke up. I was in a hotel room in Adelaide. I had left the television on, which was something I often did. For me television or radio provides company. As I looked at the screen, I saw a plane crashing into the Twin Towers. My first reaction was that I had stumbled upon a disaster film, of which I was unfamiliar. Then I realised that I was witnessing what passes as reality – and in real time.

Nobody wore black in the morning.

The aftermath continues.

Bookended by a couple of Charles

King Charles III comes to the British throne with low expectations.

King Charles III comes to the British throne with low expectations.

I was reflecting on the Restoration, the time the last Charles – Charles II ascended the throne in 1660 and realised that this was a period of British history in terms of which I had scant knowledge. On reflection, it was somewhat strange as British history was very much on the school curriculum when I was a boy; and before I transferred my interest to Roman history to complement my fondness for Latin, we were inflicted with the English kings and queens. Maybe, the school kept us away from the flagrant excesses of this king, whose personal life was not the exemplar for impressionable youths.

He allegedly had 14 children out of wedlock, but none by his Portuguese born queen, Catherine of Braganza. When the marriage contract was signed in 1662, England secured Tangier and Bombay, trading privileges in both Brazil and the Portuguese East Indies, religious and commercial freedom for English residents in Portugal, and two million Portuguese crowns (about £300,000). In return, Portugal obtained decisive English military and naval support in fighting Spain and liberty of worship for Catherine.

The last concession enabled Catherine to maintain her Roman Catholicism. The hatred for Roman Catholicism was visceral in the English Parliament; but Charles II himself was a closet Roman Catholic – for most of his reign in a very deep closest.

Balancing his conflicted religious belief was just one of his problems.

After his restoration to the throne at the age of 30, Charles’ reign started inauspiciously with the Great Plague in 1665 and then the next year the Great Fire of London. Then in 1667, the Dutch sailed up the Thames and destroyed the English navy, save for the flagship, Royal Charles, which the Dutch took back to the Netherlands. The Anglo-Dutch Wars initially did not go well for the English – in the East Indies, the Dutch even won the monopoly for nutmeg.

However, as I kept reading about England kicking the Dutch out of New Amsterdam and renaming it New York, it was made clear that Charles II was seeding an empire. New Jersey, Virginia and the Carolinas were settled at the same time when Barbados was an English outpost of slavery and sugar, the colonisation of which spilt over to the American mainland. It is fitting that in the first year of Charles III reign (or the last of his mother) Barbados has led the way in the Caribbean in becoming a republic; others will follow.

This Carolingian reign was the dawn of the British Empire and Charles II cultivated its rise, however tawdry that cultivation was. I am reminded of a Guardian reference to King Charles II granting royal approval to the Company of Adventurers of London Trading to the Ports of Africa, marking the moment at which transatlantic slavery officially began. Tawdry indeed.

Charles III is very much presiding over its embers, being briefly illuminated by all the British exquisite use of pomp and the regal vanities to turn these embers into a bonfire. But after the bonfire, night will continue to fall over that Empire which Charles 11 initiated.

The Great Fire in 1666 acted as a slum clearance agent and at the same time aborted the bubonic plague by incinerating the vectors. As a result, some of London was rebuilt in a manner that was testimony to Charles’ choice of Christopher Wren as the architect. His Baroque design owed more to St Peter’s in Rome rather than reconstructing the Gothic Old St Paul’s. The construction of St Paul’s overshadowed the 50 other churches Wren designed in the wake of the Fire.

Charles II, as well as being portrayed as a “party boy”, is associated with an efflorescence of science in England; he certainly presided over the formation of the Royal Society and the Royal Observatory was constructed during his reign. It is not known whether he ever attended any meetings of the Royal Society, but it was a time of discovery and intellectual argument.

Charles II did intervene; such as the time when he decreed that Isaac Newton need not be ordained in order to remain at Trinity College. Scientists apart from Newton included Boyle and Hooke, but one of the most unexpected friendships was that of Charles II’s with Thomas Hobbes whose Leviathan was anything but pro-monarch. But then Charles 11 had moved away from his father’s adherence to the divine right of kings.

In a world, where Oliver Cromwell’s body was exhumed and subjected to a traitor’s death, Charles II, while sometimes personally tolerant, exacted severe retribution on anybody implicated in his father’s execution, even if that association was distant. While London was the stage for the bawdy Restoration plays, both the Puritan poet and authors, John Milton and John Bunyan survived to produce some of their greatest work, despite the harsh way they were treated.

The latter benefited from the 1672 Declaration of Indulgence. Short lived, it was an initiative in religious tolerance Charles II introduced, ultimately failing to get parliamentary approval.

Charles II was important, imperfect although he may have been. Through his illegitimate children, he is an ancestor of the present Prince of Wales via his mother, Diana. She was able to trace her heredity to one of the at least four dukedoms which enshrine the genes of this prolific monarch. Thus, both Prince William and Harry – have in their genetic closet both those of Charles II as well as those of Charles III. Quite a variety of cloth. Quite a legacy.

Charles III does not have to address the religious conflict as Charles II did, resisting a parliament in trying to quash his Roman Catholic preference, and yet able to survive as the Head of the Church of England as his predecessor did. It was quite a feat, given his personal life.

Now Charles III is faced with a different challenge – a conservative parliament littered with climate deniers, and yet working through the options of promoting his “saviour of the environment” agenda.

Charles 11 ascended the throne when he was 30 years and died 24 years later. I wonder if Charles III will have that same time to achieve his agenda. One can reasonably doubt whether he will live to 98, but then the climate deniers may have won by then and the world will be no more!

One hopes that Charles III does not end his reign watching not only the extinction of empire but also that of the world.

Royal Company of Archers

The Brits do pomp. However, the number of vestments and the frequency of their usage must ensure that there must be a number of extensive spectacular wardrobes scattered along the royal routes. The amount of fancy dress which has accompanied the late Queen’s coffin was excellent theatre, but it emphasises how much the Brits spend to maintain the illusion of power through pomp concealing circumstance.

One particular set of well-suited, well-connected men, paying homage to their late Queen and carrying long bows sparked my interest. For God’s sake, it turned out to be the Royal Company of Archers. Complete with unstrung long bows and goose feathers in their flat caps, they are the sovereign’s bodyguard in Scotland.

The Company dates back to the seventeenth century, following a Scottish tradition of having gentlemen’s sporting clubs. In the eighteenth century, they were paradoxically a cover for Jacobite naughtiness. Ergo, I suppose if you did not fancy tossing the caber, archery was an alternative… and if you did not like the English royals then a bit of quivering was in order as well.

The Rules and Regulations of the Royal Company of Archers have never been printed, and, in fact, were never completed. The society may, therefore, be considered as “lawless” when within the precincts of their shooting ground. How so typical of those born to rule!

I thought its Wikipedia entry needed no embellishment in setting its relevance (or lack of same) to anything.

The main duties of the company are now ceremonial, and since the 1822 appointment as the Sovereign’s ‘Body Guard in Scotland’ for George IV’s visit to Edinburgh, include attending the Sovereign at various functions during the annual Royal Visit to Scotland when he or she approach within five miles of Edinburgh, including the Order of the Thistle investitures at The High Kirk of Edinburgh (St Giles Cathedral), the Royal Garden Party and the Ceremony of the Keys at the Palace of Holyrood-house and the presentation of new colours to Scottish regiments. At the Holyrood-house they provide the corridor guard of honour.

In this time, this band of the Establishment provided a background quirk to the main Act – that of the sovereign’s death, and the ceremonial transfer of her body from Scotland to England. The rehearsal of all this must have been going on for some time – years in all probability. The panoply is magnificent – we all get sucked into what could have been concentrated into a much shorter time frame.

The Captain General of this Company is the 10th Duke of Buccleuch, his title the result of Charles II injecting his genes in a member of the Scott family, a seriously old and wealthy Scottish family of whom Sir Walter was a prominent member of the clan. The dukedom was the reward. Charles II would be immensely pleased that another actual descendent was able to be present on such a solemn occasion, in addition to William and Harry.

The Captain General of this Company is the 10th Duke of Buccleuch, his title the result of Charles II injecting his genes in a member of the Scott family, a seriously old and wealthy Scottish family of whom Sir Walter was a prominent member of the clan. The dukedom was the reward. Charles II would be immensely pleased that another actual descendent was able to be present on such a solemn occasion, in addition to William and Harry.

Zoom

This is the stuff of fairy tales. Some years ago, a young American girl arrived in Australia on an exchange program. She became sick. She went to the doctor and was diagnosed with leukaemia. My cousin looked after her and took her round to all the doctors and through the labyrinth of tests and medical jargon. All the while she had a potential death sentence. It was an exhausting time for a young girl, and my cousin was always there to comfort and maintain optimism

After some time, she got better. She did not have leukaemia. She went back to America. She never forgot my cousin. My cousin died. The young girl was one of the employees of a start-up company, called Zoom. Yes, Zoom. She’s now a very wealthy woman, despite the Zoom stocks taking a hit recently.

She is getting married. Our family will be at the wedding.

Never Judge a Computer by its Screen

The report came to me that the Chinese doctor was accessing porn on the hospital computers. Certain nurses had seen this young doctor at night roaming the hospital and accessing multiple hospital computers, and on casually looking over the young man’s shoulder there were images of young women scantily clothed. Let me say, that doctors moving around the hospital computers at night was not specifically forbidden, but I confronted “the moonlight flit” and asked him what he was doing.

Yes, he had been accessing computers, and he had not wanted to bother us.

He was searching for a computer where he could link into Chinese search engines, and he had found one. He was using it to communicate with his sister, who was a nurse and wanted to find out whether her Chinese qualifications would enable her to be registered in Australia.

The scantily clad images were “pop-ups”, which were just – to him – incidental irritations, but had attracted the nursing staff’s attention.

We interviewed the doctor and before responding we sent our IT expert with him so he could explain exactly what he had done. Our IT expert came back and announced through one of our computers he could in fact access his sister in China.

After that, I made it clear to our Chinese doctor that his behaviour was unacceptable; if he wanted to access computers in the hospital, he must get permission. He nodded. Cultural differences did not provide any excuse.

I thought here was a case not to get trigger happy, because I do have the instincts of a “hanging judge”. The trouble with too many of us is we exact “Jedburgh justice”, in other words hang them first and try them later.

On the other hand, never ignore the “whistle-blower”; and investigate the allegations as quickly as possible, before rumours fester. Otherwise, the next moment, one is accused of a “cover-up”. All so predictable.

Wilbur Scoville

I have always been interested in the arcane , especially when it come to measurement scales.

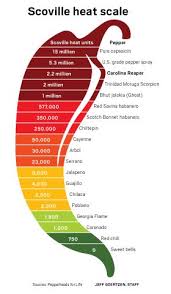

I tend to retain articles which interest me because recall of previous reading is often flawed, and although we have Google, it does not always keep all information I want handy, especially when more and more information is behind pay walls. One of the articles I kept was about the Scoville Scale, which measures the pungency or “heat” of chillies.

I tend to retain articles which interest me because recall of previous reading is often flawed, and although we have Google, it does not always keep all information I want handy, especially when more and more information is behind pay walls. One of the articles I kept was about the Scoville Scale, which measures the pungency or “heat” of chillies.

Chillies were not much part of the Australian diet until the 80s. I actually remember being introduced to chilli much earlier, in the 60’s, at Jamaica House in Carlton, which was run by a Jamaican, whom we all knew as Monty but as Rupert Montague had married Stephanie Alexander. Jamaica House was one of the first restaurants on the Lygon Street strip which bought us exotic food, including chilli. I liked the sensation of heat in the mouth. Jamaica House was where Stephanie started her culinary career.

I had to wait until on a visit to a hotel in Madras in 1983, where I ordered a vindaloo curry for really memorable “heat”. The menu warned that it would be hot. And hot it was, to the extent of inflicting pain, so hot it was. Yet at the end of a meal characterised by the ingestions of large amounts of lassi, there was a certain satisfaction, despite the incendiary nature of the vindaloo.

Oh, and I learnt very early to keep chillies away from my eyes, even when I did not think my fingers had been contaminated with them.

Wilbur Scoville, a pharmacist, came up with this way of measuring “pepper pungency” back in 1912, the Scoville Health Unit (SHU), when working for Parke-Davis.

A recent Washington Post article reads like a “eureka” moment.

Here’s how it works: Take a pepper, dry it, and dissolve it in alcohol. Then, start diluting it with sugar water. Keep diluting it until three of a panel of five humans — yes, humans — can no longer taste the heat. If you have to dilute one unit of capsaicin-infused alcohol with 10,000 units of sugar water for the pepper’s flavour to be undetectable, that pepper rates 10,000 on the Scoville scale.

It was a great system, because humans turn out to be very good at detecting capsaicin.

But they’re not nearly as good as high-performance liquid chromatographs.

Capsaicinoids can be measured without diluting them in gallons of sugar water; without assembling a panel of humans who have different perceptions of their heat and also palates that get fatigued easily.

Detecting capsaicin positively has been a job for high-performance liquid chromatography for many years. Yes, there is a centre for chilli research in Las Cruces at New Mexico State University where the doyen of chilli research Paul Bosland, was Director of the Chilli Pepper Institute and a Regents Professor of Horticulture; he has a department saturated with these high performance machines.

Bosland is now retired after 33 years maintaining chilli research, which had a 137-year history at New Mexico State University. His name is so closely tied to capsaicin that, when the school raised $1m to endow a professorship devoted to chilli research, officials named it after him – the interest on the money, they said, would pay the professor’s salary and ensure that “we will have chilli research eternally.” I would have thought that was an optimistic assessment of what one million dollars can garner by way of interest.

He uttered the hardly memorable words printed in the Washington Post: “Humans differ. We vary in our taste buds and receptors, but with a machine, we can measure very accurately.’

But all the information in this Washington Post article was hardly new, regurgitating information, which had been clearly available at least 16 years ago. The excuse then for the New Scientist 2006 article was highlighting the National Fiery Foods and Barbecue Show, which is held in Albuquerque annually, and this year attracted 170 contributors and where one can be exposed to a weekend of chilli eating.

Striving to get hotter and hotter peppers seems to be the obsession of a small variety of growers. In 2006, when the New Scientist article was written, it was claimed that the Naga Jolokia, an Indian chilli was the hottest. Then the Trinidad Scorpion Butch T pepper (1.4m SHU) succeeded as the hottest pepper in the world back in 2011. The Carolina Reaper (1.5m SHU) took the mantle two years later and has retained that position.

Whether there is any worth in creating hotter and hotter peppers, it seems not to have disturbed the “nutters”, not just wanting to eat one, but even a guy who tried to eat 123 and could go no further than 44. Time to eat them seems irrelevant; but what of the chilli challenge.

The name of benign masochism is given to these people who challenge their taste receptors with such an amount of chilli. If you are healthy, the agony generally subsides in 20 minutes, and taking milk and like products can alleviate the pain more speedily.

The next Fiery Foods and Barbecue show is in March next year. I do like New Mexico, but not that much.

Lest we Forget

As my shortness of breath progresses with my long COVID, I am both frustrated and disappointed by the lack of leadership from my erstwhile colleagues.

Below, from an opinion piece in the Washington Post, a more eloquent expression about lessons unlearned.

Today, a similar scenario is playing out in our covid-ravaged communities, and for similar reasons. As in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, our obsession with “getting back to normal” underpins much of the conversation about the pandemic. This fall we’ll be sending our children back to schools that have no covid mitigations in place and repeating the same careless mistakes we made with students after 9/11, potentially imposing a lifetime of illness in service of our desire to believe that our problems are over — or, more troublingly, that we’ve “vanquished” them.

Mouse Whisper

The term exacerbation has very little meaning to patients, we recommend to clinicians a phrase such as when your symptoms get worse instead – so writes one Ann Hutchinson, a nursing academic, writes.

Come on, Ann, When your symptoms get worse has little meaning either to many.

Rather use Are you feeling worse? is plain mouse English devoid of fancy Ancient Greek derivatives.