Our kitchen benchtop is Corian, a synthetic material composed of acrylic polymers and an aluminon trihydrate extracted from bauxite. Marble too has negligible silica, but natural granite and its synthetic offshoot Caesarstone has a variable amount up to 90 per cent silica. Corian is cheaper, but not so resistant to stains and chipping apparently as Caesarstone.

Our kitchen benchtop is Corian, a synthetic material composed of acrylic polymers and an aluminon trihydrate extracted from bauxite. Marble too has negligible silica, but natural granite and its synthetic offshoot Caesarstone has a variable amount up to 90 per cent silica. Corian is cheaper, but not so resistant to stains and chipping apparently as Caesarstone.

I have a friend whose grandfather and another relative were gold miners. Victoria had many gold mines. These blokes were dead of silicosis before I started as a medical student.

As a medical student, I learnt all about silicosis. It was a common occupational disease among those who worked in dusty environments such as quarries and in gold mining and everywhere workers were working with quartz. At the time I was a student, preventative measures such as covering nose and mouth were becoming accepted practice, so that over the next 20 years deaths from silicosis halved.

Remember that was a time when cigarette smoking was more prevalent – nothing like dust covered fingers holding a fag, and then tucked between one’s lips.

Further, it was a time when there was still residual tuberculosis in the community.

Thus, it is hardly a new threat, even though Minister Burke tried to characterise it as the “new asbestosis”. So, I am surprised by this Ministerial statement “We have now tasked Safe Work Australia to do the work to scope out what regulation is required for workplaces that deal with silica dust and to scope out, specifically, with respect to engineered stone and engineered stone benchtops to do the work starting now, on what a ban would look like.”

I would have thought there were adequate regulations, given that silicosis is hardly a new occupational disease. The question is, why the casual attitude, unless one of the jurisdictions is being resistant. I would think, license the countertop makers, and mandate wearing suitable preventative gear – both of which should improve the defence against silica dust, notwithstanding that full face respirators have been available for years. Silica is so prevalent, singling out one industry for a complete ban given its history would seem extreme. The conglomerate, Caesarstone, invented in Spain and Israel in the 1980’s became very popular in the last decade.

As one would expect, given the long association of silicosis and lung disease, the recommendation to lessen the exposure whenever possible – cutting, grinding and shaping when wet – should be a given. Ventilation and filtration systems should be used to collect silica-containing dust at source. If these engineering controls fail to eliminate the risk, then use an approved N95 respirator at the very least, and this includes whenever adjustments are required on site where cutting and grinding in a suitable wet environment is unlikely to be possible.

So, what’s causing this haggling among the Ministers for action when making countertops is just another industry dominated by working with quartz?

Colour me Malawi

I like Malawi. Some years ago, before COVID, we went there and I recalled part of that experience in a previous blog. I find tea plantations restful – the glossy greenery of camellia sinesis and the way the plantations are so ordered that they give the impression of cascading over the slopes of hill country, where the air is clean, the morning mist clinging to the vegetation. Yet here is a very labour-intensive industry – and the fact of exploitation nags at my thoughts.

After the First World War a Scot called McLean Kay set up a tea plantation of nearly 900 hectares in Southern Malawi. This estate is called Satemwa, in the centre of which is Huntington House, the residence of the Kays. We spend a couple of nights there. It is not the main tea picking season, but we pass a line of men plucking tea leaves and placing them in shoulder baskets. Here both men and women share the load, unlike earlier in the year, where I had seen in Sri Lanka near Kandy tea leaf being picked by women with their baskets supported by a headband around their foreheads. Here the baskets were supported by the shoulders and the Malawi terraces were not the precipices of the Sri Lanka tea plantations where goats, let alone women with heavy baskets, would be hard pressed to cling. Malawi was way more considerate in the way the tea had been planted for the workers.

After the First World War a Scot called McLean Kay set up a tea plantation of nearly 900 hectares in Southern Malawi. This estate is called Satemwa, in the centre of which is Huntington House, the residence of the Kays. We spend a couple of nights there. It is not the main tea picking season, but we pass a line of men plucking tea leaves and placing them in shoulder baskets. Here both men and women share the load, unlike earlier in the year, where I had seen in Sri Lanka near Kandy tea leaf being picked by women with their baskets supported by a headband around their foreheads. Here the baskets were supported by the shoulders and the Malawi terraces were not the precipices of the Sri Lanka tea plantations where goats, let alone women with heavy baskets, would be hard pressed to cling. Malawi was way more considerate in the way the tea had been planted for the workers.

The flight, followed by the long drive, tired me out. So, when we reached the House, and had been welcomed and had admired the manicured gardens with the borders of flowering bushes and trees, we were shown to our room. This was one of five – but this one special because it was where the original founder of the estate used to sleep from the time when the House was built in 1935 to when he died in 1968. The house could be coloured as lived in – all colours turn to “faded”.

However, the bed was comfortable and soon I was asleep. I awoke in the late afternoon and found that when I tried to turn on the lights, there were none. There was nobody around as I tried every light switch, every lamp – to no avail! It is a strange sensation to wake up in a completely silent world where there is no electricity; and then trying to sweep away post sleep confusion.

I padded round the house; it was deserted. There was an office, but nobody there. It was all too gloomy, so I moved to the front door. Restful has turned to restless.

Oh, how mystery builds. However, the mystery collapses when I call out to my partner and she emerges, camera in hand, around the far side of the veranda. She laughs at my situation says she is sorry that she did not wake me to tell me that there would be a power outage until 10 pm that night – load shedding. This is a common occurrence in Malawi and although the House had its own generator it was missing a vital part to make it work.

Colour the dinner dark with flickering blobs of red and amber candles and hurricane lanterns. The cognoscenti have headlamps, as does the son of the founder who comes by later in the evening to say hello. He introduces himself as “Chips” Kay. Chips is 85 years old and has grown up in Malawi. His accent betrays the fact that he was schooled in Cape Town and says he did not speak English until he was six years old. “Chips” is short for Cathcart and every Kay has Cathcart somewhere in their Christian monikers. They are of Scottish lowland stock, from Ayrshire yet have strong links to the outer islands being also Clan Maclean.

Even though he is a small man in off-white shirt and trousers, his is the demeanour of the white children born in what was once Nyasaland, but since 1958 called Malawi. He has lived through the transition from colonial authority to self-determination and prospered. He is married to Dawn and they have four children – at least they have been incorporated into the Kay family succession planning. He remains British, although he is slightly annoyed that the Malawi Government has not given him citizenship. Thus, he lives there somewhat as an outsider.

He tells us that winter rains are essential for good tea, as is the altitude. I wonder if I drew blood from him whether it would not be the colour of tannin, so immersed and knowledgeable he is on the subject.

In the morning the baboons caper across the lawn and rock lizards slide along the terrace concrete. Salmon pink is the colour of Malarone, the tablet we take each morning since malaria is endemic to Malawi and we are taking no chances, even though it is the dry season. Our defences are reinforced by repellent and mosquito nets over the bed at night.

A tea plantation would not be authentic without being invited for tea tasting. The tea tasting room is long and spare, located in the factory, a set of oblong buildings in what can be called “working white”. The room where the tea is to be tasted is off white, so as to give the impression that the tea that we shall drink has been created in a hygienic atmosphere. The factory is working full bore, with the furnaces providing heat required to dry the leaves The furnaces are fuelled by blue gum logs cut from trees, dotted as small coupes around the plantation. Blue gum can be harvested after seven years so rapid is its growth.

Brown is the tea in its various shades although we are invited to spoon teas labelled white, green and black. Familiar names like Earl Grey, Lapsang and Oolong are mentioned –and the last tea is red. This is hibiscus tea, but nobody likes the taste much.

One afternoon we drove down towards the Mozambique border. Malawi is like a gash in the Mozambican body. It is the commencement of the Rift Valley and later in our stay we would stay on Lake Malawi, a gigantic spread of water, along the line of the Rift, increasingly accompanied by the mountains towards the Tanzanian border. I have described this part of our trip in an earlier blog.

We did not cross over into Mozambique. Perhaps we could have, but flouting the rules is not a clever thing to do in Africa. Sometimes, the impression in Africa is of a lackadaisical attitude, but I wouldn’t have bet on it.

COVID changed everything in relation to Africa. We had to cancel a trip to West Africa; not whingeing but the bloody Virus has a great deal to answer for, as well as those who for one reason or not facilitated its escape into the world. We miss Africa. We miss Malawi. Given everything that has happened with us, has the World in sepia, learnt anything? Yes, some have, but the narcissists who have allowed this New Age to emerge have not.

The Amur River

“We thought we were a European country,” said Deripaska, who is founder of Rusal, the biggest aluminium producer outside China. “Now, for the next 25 years, we will think more about our Asian past.”

I have just finished reading The Amur River by Colin Thubron, an English adventurer, who recounts his journey from Mongolia, where some of the tributaries of the Amur River rise, then along the Amur River as it divides China and Russia, crisscrossing the border many times, and finally along the last stretch of the River through Russia to its mouth as it flows into the Okhotsk Sea, opposite the northern Sakhalin Island.

He catalogues with clarity this arduous trip – all the more so because at that time he had just turned 80.

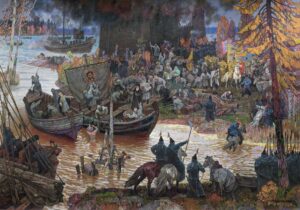

The Russians and Chinese have been in confrontation across the Amur River for centuries. In the 17th century, the Manchus, after a prolonged war ending with the siege at Albazin, then a settlement on the northern loop of the Amur River, were victorious. The Manchu let time destroy the besieged Cossacks, though as much due to disease as to war wounds, until only 20 defenders were left to surrender.

The Manchus then negotiated the Treaty of Nerchinsk and one of the conditions was the destruction of Albazin, after which the Manchu influence spread into Russia. There are quirky happenings relating to the Treaty and its aftermath. The Treaty was written in four languages (Latin also Russian, Manchu and Chinese). Then there were the Peking Albazans, who looked Chinese, dressed like Russian peasants and worshipped in Russian Orthodox churches. These people are presumed to have arisen from Cossack stock who deserted to the Manchus, built churches, even had an Orthodox monastery, and then were swept away by the Bolsheviks centuries later. The rise of Stalin was the time of the Siberian gulags where people were exiled into a terrible darkness, where the light of freedom was extinguished. Just to contemplate this is excruciating, and the West deigns to dine with the representatives of this savagery, as if Tolstoy and the Bolshoi ballet are sufficient compensation. But who am I to cast the first stone; it is just Thubron’s insight that made me shake my head.

Thubron is an Englishman who sees the beauty in this harsh area of the planet, admittedly though he was there at the best time of the year. His descriptions of the landscape are beautifully evocative – these landscapes are diverse visual seams, an essential art form for successful travel writers. To him there was a certain familiarity as he had travelled across the same territory 20 years ago when the political situation had more political fluidity in the pre-Putin and pre-Xi Jinping eras.

Yet the condition in this part of the country does reflect the overall politico-economic situation of the country. When the central government is weak, and the other relatively strong, then it is reflected in the respective local economic activity on either side of the Amur River. Currently, the Chinese are building large cities, whereas the Russian side of the river is impoverished. Here are the signs of a time when Russia once held sway of the region for some time after the Treaty mentioned above. China became weaker and moreover was preoccupied by restlessness in the South of the country and Formosa for a long period. Then later the war with Japan debilitated China further, far more than Russia. Times change. His overall current description is of Russian decay.

The two countries may not have much in common culturally, but today it seems the two countries have tacitly agreed there is no point warring over the territory. Power is economic, not military. This has been asserted by the Chinese – the Russians do the menial work moving the Chinese-made products across the river. Yet it was only in 1986 in Vladivostok that Gorbachev asserted that the countries were confined to the banks and the border was the navigable Amur in between, and his assertion remains as a given. In other words, cultural conflict has not necessarily been translated into armed conflict, apart from a few cross-border skirmishes.

The river itself is partially navigable but before World War I, there were comfortable boat trips along that part of the river. Thubron describes a boat trip made in 1914 by an Australian woman, Helen Gaunt, who relished the boat’s velvet upholstery and mahogany panelling with lunches of sturgeon, chicken and red caviar ‘spread like marmalade on an English breakfast table’. Nevertheless, the hope that the river would provide a trade route opening up Siberia to the Pacific Ocean was dashed by the shallowness of the river and particularly at the mouth of river there are many sandbanks.

Russia has concentrated its port facilities 800 miles south at Vladivostok. The Amur may be three miles wide at its mouth, but he describes it as “running at five knots of silvered mud”. And as always he outlines the Siberian conundrum of “unblemished hills that fall in spurs of forest light” on one side of the river with walks along a jetty on the other side “the carcasses of iron barges lie sunk under its water, and its shingle is heaped with fallen bricks and concrete, tangles of wire and chains”. Ah, civilisation in all its brutality.

The book ends there. Was the voyage worth the difficulty, the hardship? I suppose getting to the finish is in itself an achievement and his contemporary insights must be unique for a European journeying in an Asia, where Russia obviously is a player, but seemingly subservient to China. Nevertheless, the insights of his journey are very complementary to the ruminations of the Russian oligarch at the head of this blog.

Superannuation Taylored?

Taylor is one of seven Liberal MPs in the 46th Parliament of Australia who have obtained degrees at an Oxbridge or Ivy League university, the others being Alan Tudge, Josh Frydenberg, Andrew Laming, Dave Sharma, Greg Hunt and Paul Fletcher – Wikipedia entry.

I watched Angus Taylor on Sunday. I always thought that this Shadow Treasurer was a garrulous “cockie” whose diction had been caused by having a silver ladle in his mouth for too long a time. The above excerpt from his long entry in Wikipedia is amusing as it seems to outline the March of the Duds. Unlike most Wikipedia biographies, which can be interminably dull, his entry is engaging and lists all his alleged malfeasance.

I had never before watched him in a long interview. Despite his mien, he is not dumb, and his acrobatics with the truth absolutely magical; but the ease with which he does it shows that his education at The King’s School and Oxford has not gone for nought.

He can talk nonsense with the surety that the viewer knows that he knows that is nonsense. He is at ease with this paradox of the smart man hiding behind his public school interpretation of Crocodile Dundee, as anybody could be. If he can avoid being found guilty of any malfeasance, he is assuredly the next Coalition Party leader – nor will the current National Party crop be able to stand up to him once the time comes for him to make his move.

His comments on superannuation made me think. The Prophet Taylor tells all what their superannuation package will be like in 50 years, a time relevant to my grandchildren. I started to rack my brains about my attitude to superannuation when I was their age, an age when Taylor warns young people are going to be indexed out of their retirement funds because of that Jim Chalmers, the one that Albanese cannot drown in his endless pot of political molasses. I didn’t give superannuation a thought in my twenties.

In my thirties, because I moved around in salaried appointment, I did not accumulate any pension/superannuation funds. There was no reciprocity. My father died early in the 70s and left me some money, which was subject to inheritance tax, now abolished. At the end of the decade, I gained employment where there was at the time a generous superannuation scheme so that, after five years, I could take the whole amount including the employer’s contribution. It was useful to access it at that time.

Having done my five years I, with another bloke, formed a consultancy, and my superannuation thereafter was paid from the company that employed me. Thus, from the mid-eighties I did not benefit from the wave of entitlement that the politicians in cahoots with the public service controlled what they could take from the system without being called “rapacious”.

I remember the cries that went on about “getting better people into Parliament if they were paid more”. One does not hear that now the entitlements have soared, yet the standard of politician has not improved. Imagine some of them running a business? Angus Taylor stands out as one who could. Yet he defends the current superannuation arrangements rather than agreeing to a modest tax designed to improve the Government’s ability to pay for a country progressively rotting under the effects of climate change and the coddling of the Australian plutocracy, which had been so rampant when he was in Government.

In 1992 the then Prime Minister, Paul Keating introduced the policy of compulsory superannuation contributions under the Superannuation Guarantee scheme. Since this time this has grown to over $1.5 trillion and is argued as one of the key drivers of Australia’s national saving rate. This has become an asset, and like all assets, where a tax is fair and reasonable, a tax such as proposed seems to be so. Therefore Angus Taylor, you know how confected your opposition is; we do too; and judging by the polls so does the general populace.

Or perhaps it is all your working with cows in the dairying industry, that Mr Taylor, you are having difficulty in recognising caic tarbh. Surely not.

A Crackling Good Idea

The following dermal delights appeared recently in the Washington Post. I normally stay away from recipes, but what next? Omentum? (Black pudding ingredient among Austrian Southern Tyrolean yodellers) Tendons? (Chinese of course, slow cooked beef tendons)

Suddenly Tim Ma had skin in the game.

The chef behind some Washington restaurants was recently in Austin in Texas and was making a simple pork skin chicharrón. “We just could not get it to puff,” he recalled. “We scraped off the fat, dehydrated it, fried it at the right temperature, and it just wouldn’t puff. But then we tried another batch that looked exactly the same, and it puffed up immediately. So we stared at it like, ‘What the hell is going on?’ It’s a whole other world of science. I blame Texas humidity.”

Ma is not alone in his embrace of that other world of science. Chefs across the country are showing more skin: in everyday chicken skin salads and cow skin stews as well as fancy turns of, say, salmon skin chicharrón in Los Angeles. Or casual eats like the Chinese-Cajun cracklin’ in New Orleans and the curry noodle sandwich with crispy guinea hen skin in Durham, N.C. Even José Andrés’ grilled vegetables are skin-on. Every skin everywhere all at once.

“It’s cool to take something apart, treat each piece differently and put the pieces back together,” Ma said. “It’s a technique thing, but it’s also a good way to introduce different flavours, different textures.”

History does not celebrate the first skin-eaters, cultures around the world now enjoy skin recipes — whether Canadian scrunchions (pork rind), Indonesian krupuk kulit (beef skin), Jewish gribenes (chicken or goose skin cracklings with fried onions), Mexican cueritos (pork rind), Slavic cvarci (pork crackling) or Vietnamese tóp mo (fried pork fat).

History does not celebrate the first skin-eaters, cultures around the world now enjoy skin recipes — whether Canadian scrunchions (pork rind), Indonesian krupuk kulit (beef skin), Jewish gribenes (chicken or goose skin cracklings with fried onions), Mexican cueritos (pork rind), Slavic cvarci (pork crackling) or Vietnamese tóp mo (fried pork fat).

At The Mary Lane in Manhattan, chef Andrew Sutin keeps reinventing his menu’s trout dish with skin: first with a dried-skin crumble, then with playful curls of fried skin on sautéed fillets and now layered between sliced leeks in a potato soup topped with trout.

“It’s a fresh approach to something that’s already there,” he said, comparing it to a “bonus track” on an album. “Your creative landscape is doubled.” Sutin compared skins’ moment in the sun to the rise of aioli and yolk-heavy pasta, which came in tandem with the popularity of egg-white omelettes and egg-white cocktails earlier this century.

“We’re trying to push the envelope into interesting adventure,” he said. “It’s delicious. It adds texture. And it’s not too far out there, really. I don’t want to serve something weird for the sake of weirdness.”

Skin is not magic. Celebrity Chinese chef Zhenxiang Dong built his whole menu around duck skin so delicate that it easily shattered. His American debut flopped, despite counting Michelle Obama among its duck skin fans. There are also limits to what diners will stomach: Andrew Zimmern, host of the Travel Channel show “Bizarre Foods”, once recalled with revulsion that he was almost served a human baby’s foreskin in Madagascar.

Even in less-extreme circumstances, a reluctance bordering on squeamishness around eating skin is not uncommon. “My dad loves making kilawin with the cow’s skin or goat skin,” said Sheldon Simeon, a Hawaiian chef with his own recipe for Ilocano cow skin. “Not something that I do in my restaurants, though.” Asked why not, he declined to answer.

Inspired by cotenne (an Italian pork skin crackling) as well as bì heo (Vietnamese shredded pork skin noodles), New Orleans-transplanted-to-New York chef, Dominick Lee makes a roast beef tagliatelle, with a gluten-free option of pork skin noodles. He also uses dried skin as a kind of furikake-style flavour bomb with rice. It can be a tough sell. “It’s not often someone wants to talk about skin,” he said. “You’re either extremely interested in food or you’re Buffalo Bill.”

In Savannah, Ga., Rob Newton credited ketogenic eating with a rediscovery of skin. “Keto diets have really helped the eating of skin,” he said. “You can eat chicharrónes or fish skins in cured egg yolk. People want their crunchy, salty thing without a potato or corn, and pig skin has really stepped into that role.” He’s currently developing a kind of terrine he saw in Mexico City that incorporates pulverized chicharrónes.

A desire for zero-waste sustainability helps, too. “We want to honour every bit of the animal,” Newton said. “We don’t waste the bones, the feet, the ears, nothing. This is a way to help do that. And that makes us feel good, like we’re doing the right thing, because we are.”

Mouse Whisper

From To a Mouse

I’m truly sorry man’s dominion,

Has broken nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

Better late than never for Mr Burn’s annual day, and belatedly remembering to drink the classic smoked fish soup and nibble the essential haggis, neeps and tatties – all rounded off with a traditional clootie dumpling and a dram of whisky.

Cho sona ri luch ann an lofa