Pablo Picasso died in 1973. Françoise Gilot was probably the most well known of his wives and lovers. She was 40 years younger than Picasso. She has just died. In her obituary, which variously appeared in the New York Times and Boston Globe, it was noted she was a very good painter in her own right. Given the excoriating reviews of the Hannah Gadsby curated Pablo-matic, currently at the Brooklyn Museum, there seems to be an increasing concentration on Picasso the Misogynist rather than Picasso the Painter. Picasso was famously quoted as saying that there were two kinds of women: goddesses or doormats. He was appalling to women – to those with whom he slept, or those with whom he tried to sleep. Given the times, Gadsby has her following, even if the art critics seem to be universally panning the exhibition which runs until October.

My view? When Gadsby does something comparable to the painting of Guernica, then I may take her seriously.

Meanwhile, an excerpt from the obituary of Françoise Gilot:

Françoise Gilot, an accomplished painter whose art was eclipsed by her long and stormy romantic relationship with a much older Pablo Picasso, and who alone among his many mistresses walked out on him, died Tuesday at a hospital in Manhattan. She was 101.

“You imagine people will be interested in you?” Ms. Gilot quoted a surprised Picasso as saying after she told him that she was leaving him. “They won’t ever, really, just for yourself. Even if you think people like you, it will only be a kind of curiosity they will have about a person whose life touched mine so intimately.”

But unlike his two wives and other mistresses, Ms. Gilot rebuilt her life after she ended the relationship, in 1953, almost a decade after it had begun despite an age difference of 40 years. She continued painting and exhibiting her work and wrote books.

In 1970, she married Jonas Salk, the American medical researcher who developed the first safe polio vaccine. Still, it was for her romance with Picasso that the public knew her best, particularly after her memoir, “Life with Picasso,” written with Carlton Lake, was published in 1964. It became an international bestseller and so infuriated Picasso that he broke off all contact with Ms. Gilot and their two children, Claude and Paloma Picasso.

Ms. Gilot’s frank and often sympathetic account of their relationship — she dedicated the book “to Pablo” — provided much of the material for the 1996 Merchant-Ivory movie, “Surviving Picasso,” in which she was played by Natascha McElhone, with Anthony Hopkins as Picasso.

If Ms. Gilot’s book sold well, so has her art. With her work in more than a dozen museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, her paintings fetched increasingly higher prices well into her later years.

Gilot showed herself to be an artist who did not need to live within the penumbra of Picasso. Her painting of her daughter, Paloma (Paloma à la Guitare) fetched US$1.3M in 2021.

How does that affect one’s appreciation of each of their extraordinary artistic talent? Or “should”? Picasso’s portrait of Françoise Gilot was anticipated to reach US$12.8m.

Caravaggio was a murderer. His paintings hang in cathedrals.

Closer to home, I have a couple of Dennis Nona works.

Do we need to grade the size of the stone we throw at the past – and the present?

Guernica

When I researched the bombing, I read stories of a number of Guernica victims who appeared at hospitals with strange symptoms: Their hands were mutilated. The injuries weren’t from bombing of burning, but from their insistence on digging barehanded through jagged rubble — until the flesh tore from their bones — in the single-minded attempt to save their loved ones. Dave Boling

Dave Boling is an American sports journalist, not a person noted for historical novels. His motivation for writing the book was rooted in his marriage to a woman of Basque heritage, her grandparents having come from Biscay, (the Basque province now known in official documents as Bizkaia) to herd sheep in the mountains of Wyoming, Nevada, Idaho and California. He has said that his in-laws introduced him to the pleasures of spicy Basque food and red wine and tried to teach him their folk dances. They also indoctrinated him about their strong familial allegiances and their long history of oppression. It is hard to not to have sympathy for the Basques but that has been tempered by the assassination and bombings perpetuated by ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) between 1959 and 2018. Its goal was gaining independence for the Spanish Basques by any means.

The actual destruction of the Basque village of Guernica is the central point of a novel which essentially follows the fortunes of a Basque family which settled in Guernica. I agree with the review in the Independent:

The intended heartiness of the rustic idyll generates a sense of ominous calm. It explodes halfway through this saga, in the Luftwaffe’s experiment, at Franco’s invitation, of carpet-bombing the town and strafing survivors with machine guns. Children fused together, mothers crushed under rubble, old men incinerated – the horror is amplified by the hideous cynicism of attacking a civilian population.

Still, I found it hard to read, probably because I thought that it would concentrate on the destruction of Guernica, but this was a novel of inevitability, thus replacing any sense of premonition of what is to befall the family.

I have been to Bilbao, the capital of the Biscay province, several times and always visited that spectacular Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim Museum. The 3.4 metre floral “Westie”, called Puppy, was installed in 1997 and stands as sentinel to the building. I had thought Guernica would end up here, but I have seen it in three locations. During the Franco period, it was in New York. I remember seeing this painting there for the first time. However, I am confused because if you had asked me where I saw it in New York, I would have sworn it was the Guggenheim Museum, but in fact it was in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art. Later I saw the painting again in the Prado and then in its final placement in the Sofia Reina, where it lives in solitary splendour.

Picasso’s epic painting, where his intertwined black and white images define the chaotic cruelty of war, is one of the few paintings that I can sit and look at it for more than any other image, with the exception perhaps of the whole mosaic tableau which lines the walls of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. There is so much to see in Picasso’s Guernica, which embraces premeditated carnage, the futility of which is the natural corollary of cruelty. Some may say that the Nazis, the Falangists, the Italian Fascists were just a clinical experiment in war, but the end product was so appalling in its results – a danse chaotique. Guernica died; but the Basques live on.

Barcelona

Rambla comes from the Arabic word ramla or رمل which means sand and refers to the sandy deposit which would gather in the bed of the stream where the street now exists.

Barcelona, located in Catalonia, is one of the edgiest cities in the world that I have visited, both well before the 1992 Olympic Games and after. Catalonia always wants to free itself from Castilian Spain, its citizens having a separate language and flag. It was in this city where Picasso found his artistic limbs. He had been born in Malaga and his family moved to Barcelona in 1895. In Barcelona, Picasso moved among a circle of Catalan artists and writers who met at the café Els Quatre Gats (“The Four Cats,”) styled after the Chat Noir [“Black Cat”] in Paris. Picasso had his first Barcelona exhibition of more than 50 portraits here in February 1900.

It was strange to think that the building of La Sagrada Familia had already been in construction for 17 years at that time.

When I first went to Barcelona in the late 1980’s, preparation for the Olympic Games was well underway. By contrast there seemed to be no sign of activity on the Sagrada site. Rubble was strewn around the base of the unfinished cathedral and high chain wire fence prevented access. Yet I marvelled both at the extent of this unfinished building and how much there was still to do, given it had been over a century since work started. I had seen the plan with that giant spire, which I understood at the time they did not know how to build. Still, this first visit to Barcelona was the first of several during which time the whole process accelerated. At the same time Gaudi became increasingly well known and La Sagrada Familia became a magnet for tourists. Since then, there have emerged entry fees and the camera and iPhone toting queues.

I’ve not been there for years but the last time I was there, the interiors were almost complete, and it was estimated that La Sagrada would be finished in 2028, although there were still a number of spires to be constructed. The reds, blues, yellows and greens of the glass defined the mood of the interior and the early morning was a good time to feel the clarity of the filtered morning sun rays, a burst of golden colour, in the vast nave and chancel.

I am not much of a fan of the Gaudi Park Güell, commissioned by a wealthy textile manufacturer, which demonstrates many of Gaudi’s signature architectural devices, including catenary arches and tessellated finishes. Gaudi’s land of strange shapes and figurines jar, despite the fact that it is very cleverly constructed on the side of a hill, where the terraced pathways invite you to walk and look.

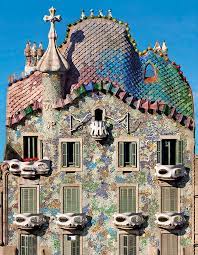

Nevertheless, there is one special Gaudi building – the Casa Batiló – in the centre of Barcelona. To me, like the best of Gaudi, it seems to have been lifted from another world and plonked into a conventional streetscape, such that the other buildings fade, and all you see is the Gaudi building. All the shapes have fancy architectural names, but from the outside, the Casa Batiló is a mottled tapestry with a variety of openings indicating a door or window. Inside, the rooms need to accommodate those adventurous shapes, and the blue theme is evident in the Noble room. Gaudi is confronting and to me, a building like the cathedral or indeed Casa Batiló, is to be fascinated by the mind that could design such an edifice. I wonder whether it may have provided some inspiration for Picasso. It is extremely problematical whether Gaudi ever met Picasso. They moved in very different circles.

I have been attracted to Barcelona because of George Orwell’s book written about the Spanish Civil War, Homage to Catalonia. This is one of the most evocative pieces about a War when democracy died along with the Republic. Catalonia was not only Republican but where the black flag of the Anarchists also flew aloft. Like Guernica, Barcelona was bombed in 1936 by the Italians, with considerable loss of life. I found it ironic that the Barcelona Olympic Games, some 60 years later, was stage managed by Juan Antonio Samaranch who, although a Catalan, was an avowed Fascist functionary during the Franco regime, as well as being a supernumerary in Opus Dei.

The first time I stayed in Barcelona was in an old hotel on Las Ramblas, the central thoroughfare of Barcelona where the city action takes place. I had been warned that I had to watch out for pickpockets. My first encounter of Las Ramblas, as I turned the corner, was of a young man running straight at me being pursued by a couple of policemen. He swerved away and then disappeared up an alleyway being closely pursued.

Then there was a young woman walking by, talking intently into her mobile phone, except that the mobile phone would not be invented for another 20 years. However, her hand imitated the future so well, even contributing to the mime with one finger acting as the antenna.

The old wharf area still existed beyond the statue of Christopher Columbus and there was a clutter of unpretentious places to eat – hardly classifiable as restaurants. Here I was introduced to suquet de peix. This is a Catalan fish stew with fish – probably monkfish – squid, prawns and mussels. Since I don’t much like monkfish, I have never placed it on my memorable fish list. All this disappeared with the Olympic Games, with the creation of a marina and modern waterside restaurants connected by a footbridge to Las Ramblas and where, at night, there was now a spectacular run of fish restaurants.

Las Ramblas, with its market and its liveliness, has a strong connection to Miro. There is a museum dedicated to Miro, but the most striking link to him is the mosaic on Las Ramblas. You really only get a good view of it when there are few people around, and we used to go down the thoroughfare in the early morning and stop for a cup of coffee and a view of Miro on the way back.

If there was anything of importance happening in Barcelona, well wait long enough on Las Ramblas and something memorable will happen. We happened to be in Barcelona on one sunny day in 2009, when a double decker bus with an open deck rolled by, crammed with exultant footballers covered in the blue and garnet colours of the Barcelona Football Club. I remember recognising a young Lionel Messi, and the street crowd going wild. I had never been in person to witness a latter-day Triumph.

Since our last visit the Catalan push for independence has been a political thorn for Madrid, deeply embedded despite extravagant attempts to remove it. Las Ramblas has seen plenty of action by a protesting population in these last years.

As for Picasso, there is a museum where some of his vast output of paintings and drawings hang. In addition, as with any person who spent significant time in the place where ideas and skills were formed, there is a trail that one can follow. I have done such a trail in Paris, following the footsteps of Hemingway, but not here in Barcelona (until I started writing this blog my central interest in Picasso was Guernica). Let this interest rest with something Picasso said about Barcelona in 1936. “Barcelona the beautiful and wise, where I left so many things hanging on the altar of happiness…”, but not Guernica!

Not Pablo

I hesitated to add this scatological piece, but it does have a certain relevance to all that has gone before in this thematic blog. Boys’ schools have always been places where teachers, especially those who have been part of the furniture for many years, earn nicknames. One of the most well-known was the teacher who always seem to cock his head, perhaps he had a wry neck. Boys never worried in the past about such minor matters as disability. He was known as Isaiah, because “one eye was higher than the other”.

We had a teacher called Grenness, and naturally earned the epithet of “mossy”. Then there were names that fitted together, such as Banks called “dogger” or Giles called “spudda”, which may now seem to be somewhat arcane. Then there were names based on appearance – monkey, bullfrog, mousey, bulldog contracted to bully; predilection – pansy; idiosyncratic – toss, johnny, sponge, shovel; or just behavioural – witness the English teacher with the moniker “Picasso”. Enough said.

I, Consultant

Just after I started as a medical administrator at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in 1971, I was introduced to Peter Davenport, a former RN lieutenant commander, who had become a consultant for PA Management. This firm had been employed to improve the efficiency of the way the hospital should function. PA Management had attracted attention by the way it had reformed the Sydney Hospital, at a time when there were questions being raised about the future of that hospital, given there was a surfeit of inner city hospitals. The oldest, the Sydney Hospital, was located close to Parliament House, but otherwise it had a fading catchment area.

I came to the Hospital just after Davenport had started this consultancy, using participative management techniques. Unlike the consultants who come in and charge an exorbitant fee to observe, Davenport actually immersed himself in the job. The first area that he addressed was the operating theatre complex. The key to participative management is to get the leaders, at that time inevitably the medical specialists, and induce them to surrender some of their individuality to work in a participative model, rather than just issuing orders. It was a change, and I came into this world where there was emphasis on doing better.

Participative management, to work, needs to have the support of the most influential – in this case Sir Benjamin Rank and Dr Jock Frew, a formidable duo, who had served during World War II and knew all about hierarchal management. This was much loved by all uniform services, and that included the medical staff of teaching hospitals. The then Medical Superintendent, John Yeatman, assigned me to work with the consultant. Davenport and I were then in our early 30s and hit it off very early. The upshot was that we were perceived as achieving the objectives, which were agreed across the various departments, in addition to the operating theatres.

Therefore, I had a positive view of consultants, and a decade later when I had completed five years as Deputy Secretary-General of the Australian Medical Association (AMA), I set up a consultancy firm, Diagnosis, with a transport economist I had known for years, Dr Robert Wilson. He was also a particularly good cost accountant as well as having one of the most rounded and perspicacious brains I’ve ever encountered. When I was with the AMA we had worked together on its submission to a Federally-funded review of the health care system in 1980.

Initially it was hard going attracting work, especially as I was debarred from getting any work from my previous employer. It took some time for us to be recognised as the form of consultancy whereby we were flogging our knowledge and skills in navigating a system, where I have always said that, to be truly useful, one must be fluent in the language of health. Beginning in the late 80s public servants, already pensioned off well remunerated, were recruited by the big accounting firms ignorant in health but able to manipulate numbers. These public servants often had an incomplete knowledge of health but one that was serviceable for about two years. The sophistication of the recruitment process was ramped up, together with the fees charged to government. As my ancestor would say, tell me pray where any of these consultancies yielded anything of value when addressing the structure of the health system, whereas I can point to areas where Diagnosis did influence the outcomes in a positive manner.

On occasions I did use the skills engendered working with Peter Davenport and elements of neurolinguistics I’d gleaned without any formal training. I remembered one of the famous conclusions of the Australian sociologist, Elton Mayo, who made his mark in the 1920s with his work in the Hawthorne Chicago plant of the Western Electric Company. He noted that output of work is a function of work satisfaction, “which turns upon the informal pattern of the work group”.

However, it seems that today being a consultant with the highest remuneration package relies on who you know rather than what you may provide for change and, laughably, the cost efficiency of the project. The basic work is done by the graduate serfs, who know how to write basic English and regurgitate the ruminants which are increasingly available on artificial intelligence without having any real effect on the outcome. The ultimate greater sin is to recommend at great cost what has not worked in the past.

Meanwhile, the consultancy firms pillage the gravy train as it proceeds along with its impedimenta of ex-politicians and ex-public servants, who have spun through the revolving door into this Wonderland where the gravy is golden.

Q.E.D. as Euclid would say.

Mouse Whisper

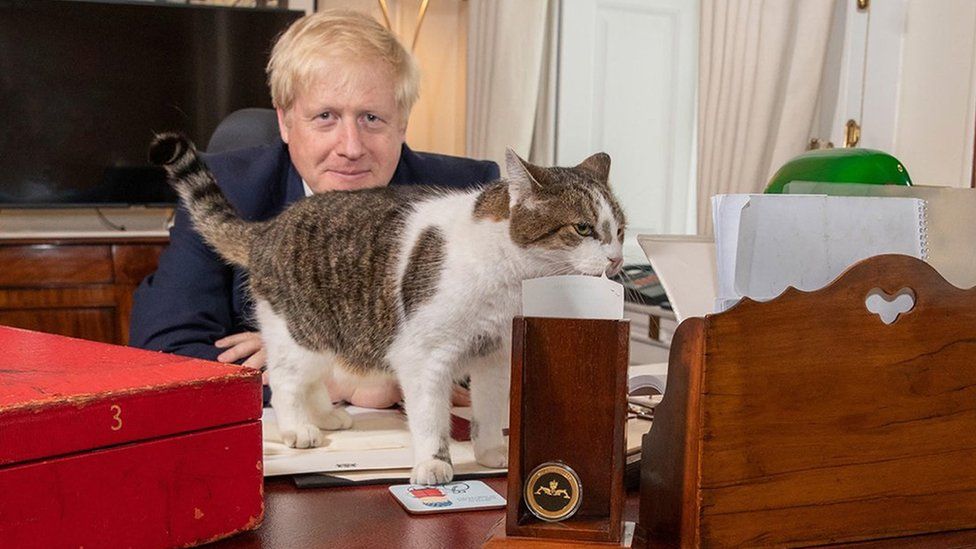

For me to quote a Cat is Something!

Larry the Cat, Guardian and Chief Mouser (ugh), No 10 Downing Street:

“I’m pleased that Boris Johnson’s resignation will give him time to see more of his children, possibly even all of them.”