I have an admission to make.

On one of the secondary TV channels during each weekday, films generally British studios’ productions from the 40s and 50s are shown before an endless parade of American Tawdry aka Murder She Wrote with the wonderful Anglo-American actress Angela Lansbury as J.B. Fletcher, the American writer who has the unique ability to always be a “busybody without portfolio” wherever there is a corpse. Murder She Wrote became standard American TV Sunday night fare for a decade in the 80s and 90s.

Before I diverge onto a discussion about this slice of American life, which runs on formulaic lines, one never knows what film will be run in the afternoon slot. Most of these films are very dated and for that matter very formulaic. These were films from childhood. The “Carry On” and “St Trinian’s” movies are hangovers from the double meaning seaside postcards, in themselves a product of vaudeville comedy. Nevertheless, the film one day last week was a classic – The Captain’s Paradise. It was set against a background of Gibraltar and Tangier.

Alec Guinness is captain of a passenger ferry which plies between Gibraltar and Tangier. The film is one of his best; it has aged well. Besides, once Destination Gibraltar was top of my “bucket list” to visit.

The film thus reminded me of the times when the one place in the World that I wanted to see was the Rock of Gibraltar. It always appeared in the photographs taken by my older relatives who as young adults were making the obligatory working holiday in Great Britain. After all, World War II was over, the “old country” beckoned and jobs were easy to obtain there. For my relatives the only way to go was by ship. The number of ebony elephants on the mantelpieces of suburbia attested to memorabilia from the first overseas port of call – Colombo. Here these young Australians on their post-election venture were being introduced to our neighbouring continent which the then White Australia policy had made a pariah.

In the six weeks ship journey, the ship would berth in Colombo, Aden, Suez and Gibraltar before the last dash across the Bay of Biscay to Southampton… “civilisation” at last reached. Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal in 1956 changed all that. However, it did not alter my resolve to get to see the Rock. For years, while Franco was in power, apart from ship, the only way to Gibraltar was by air. After Franco’s death, delayed until 1982, the border was open for pedestrians and then for cars from 1986.

Gibraltar has always been an armed camp and harbour from the time it was ceded to Great Britain by Spain in 1713. Despite agitation from Spain, it has remained in British hands since. The Gibraltarians are probably the greatest bunch of loyalists to the British Crown together with the Protestant Northern Irish.

As you drive through southern Spain towards Gibraltar the signs are small and infrequent. The Rock is hidden, you begin to think. Eventually when you negotiate these roads, the border appears. The Rock suddenly looms. It is impressive. Limestone, an irregular pyramid, it rises 420 metres from the sea; it is smaller than Uluru, which is shaped more like an upturned ark, and of sandstone, which is brilliantly suffused with ochre red at sunset. The Rock just looms.

Initially we were held up from going over the border, by an airliner taking off. Cars have to cross the runways to reach Gibraltar itself. At the time, we had spent some time in Southern Spain, with all the exotic surroundings of Granada, Cordoba and Seville.

Gibraltar, as my wife surmised, lacked such Iberian romance. It was just like a British holiday camp. The food was definitely substandard British fare; no tapas here. No traditional Gibraltarian food either. The hotel lounge was littered with men in sharp suits or contrived t-shirt informality doing business. It could be anywhere in provincial England. One small highlight was being able to gaze down from our room’s balcony into the deep blue sea – just a vertical drop and waves far below languidly breaking on rock underpinning the hotel.

There were the sights. The panorama view from the peak and along the way of the Mediterranean looking over to Northern Africa is a spectacular view, particularly when the sun shines. Below is that spectacular view of Sea meeting Ocean, and the continuing movement of ships everywhere. This is a busy sea road.

Yes, seeing the Rock for the first time fulfilled my long term wish, but unlike visits to the Spanish cities, the British seemed to have spent their time building defences – a warren of tunnels and cannon pointing towards the sea; and of naval facilities. The Rock is the attraction; but moving around the Rock means being annoyed by troops of Barbary apes. Being unique to Europe, these nuisances have free range and tourists are magnets to annoy.

Yes, you wander around, and the gardens are sub-tropical pretty, the centre of town picturesque and there is photo of me exiting a traditional red British Tardis – but in the end, what is Gibraltarian culture, but the Rock.

In retrospect would the Rock have been Number One on my bucket list of what to see? Probably not, but nobody can consult the Retrospect. So, as my Italian friend would say “Chissa!”

There is always a Clare Castle – The Hotels I mean.

Clare Castle Hotels can be found all around Australia. I remember one in Carlton when I was a medical student at the University of Melbourne. The food was simple but great, and we crammed into the downstairs dining room at the time of the NeoBarbaric age when the Wowsers ruled. At dinner, alcohol was served from bottles we had bought, wrapped in brown paper bags . “(Alcohol) bought into a hotel” – said slowly, compounds the idiocy of that Victorian period.

At the same time, along the passage beside the dining room and up the stairs there was the patter of migrant men in the main coming and going ceaselessly. They weren’t carrying brown paper bags, and we concluded that they were not the local chapter of the Temperance Union.

This week I came across an essay I wrote about the South Australian town, Kapunda, some years ago when I was trying to find more about my great grandfather, Michael Egan. I have previously written about the short period he spent in Kapunda when he first arrived with his family in 1849 on the “Cheapside”.

We are Egans from Co Clare. Kapunda has a Clare Castle pub. Here in Kapunda was the first commercial mine in Australia. Copper was mined here, and from the start, Welsh miners specially recruited for their skill in smelting were the first to work the mine. They were followed by Cornish, German and Irish immigrants, one of whom was Michael Egan.

The Kapunda bosses were Anglo-Irish – Bagot, Blood and Dutton, although Dutton did not last long and sold his shares and left. In the case of nearby Burra, its rich copper lode was discovered by a shepherd but the beneficiaries were the fortunate “Snobs”, early investors in the South Australian Mining Association who made fabulous profits on their investments, and if they did not retreat with their money to England became the backbone of the Adelaide Club.

The success of the mines was shown by miners’ pay being up to £2 a week. Tents gave way to two-roomed cottages built from stone and mud. Some were wattle and daub. There were no verandas. Walls were whitewashed to reflect the heat. Roofs were shingle or thatch. The one window aperture often had a bag of whitewash hanging over it.

When Michael Egan arrived, he would have seen the copper ore being bagged in hundredweights (cwt) lots for despatch to Port Adelaide. To guide the drays laden with ore, a furrowed track had been driven into the ground between Kapunda and Gawler, 30 kms to the South.

Meanwhile the brackish Light River needed to be pumped from the shafts. This water was turned to advantage in washing the ore, enabling the ore to be tamped down prior to it being sent in the first years for smelting in Wales. Eventually smelting facilities were built close to the mines. By that time Michael and his brood had decamped to Victoria. He probably listened to the sirens of “gold” emanating from the discovery in Ballarat in 1851. As was written, “The sudden cries of ‘Gold’ from the fields in Victoria brought everything to a grinding halt. Workers downed tools and rushed to the Victorian diggings.” Michael Egan was one of these, and the “Kapunda mines would have been deserted had four miners been left to prevent the mine from flooding.” I suspect the writer was being somewhat melodramatic.

These mines lasted until 1871, but other copper mines opened up and today the Roxby Downs mine is second only to Mount Isa in its copper output.

At the time of the Kapunda discovery, it should be remembered South Australia was broke. Drought had prevailed, and the Goyder line was more than a decade away calculated to define what land below the line was viable for agriculture and above the line what was not. Burra, close to Kapunda, was also a copper mining township. Even though Burra was settled after Kapunda for a short period it was in fact the largest inland town in Australia.

I do remember Kapunda for its embroidery, but we passed on buying the antimacassers and doilies. Burra I remember somewhat differently. It was late on a Saturday morning and for some reason I drifted into the Saltbush store in Burra. It was not long after the business had started. Two women farmers had decided on a career extension into making clothing and creating a fashion outlet in Burra. I saw a pair of moleskins, but they needed alteration. I looked at my watch; it was almost closing time and we were not coming back this way. No worries, said Elspeth, one of the Saltbush founders, she would make the alterations immediately if we could wait. Astonished by the service, we did. Very impressive, and we shopped there when we could, for years after.

Life is Peachy

Over ten years being associated with orchards in the Goulburn Valley made one well aware that after cherries and apricots, the first available Spring fruit was followed quickly by peaches and nectarines and then after Christmas, with berries, came pears and a long tail of various types of apples – and over time there was a shift in the popularity of various types. Peaches were no exception. The prime production of peaches was of the deep yellow clingstone variety which were good for canning, but as fresh eating fruit not as good as the freestone variety. The clingstone although juicy, had skin often difficult to remove. Clingstone peaches are the staple for canned peaches but freestone peaches are becoming more popular. The problem with peaches, which look so attractive, is that such attraction is very ephemeral. Fresh peaches have short shelf life without refrigeration, and it was rare to find them being sold on the roadside.

Over ten years being associated with orchards in the Goulburn Valley made one well aware that after cherries and apricots, the first available Spring fruit was followed quickly by peaches and nectarines and then after Christmas, with berries, came pears and a long tail of various types of apples – and over time there was a shift in the popularity of various types. Peaches were no exception. The prime production of peaches was of the deep yellow clingstone variety which were good for canning, but as fresh eating fruit not as good as the freestone variety. The clingstone although juicy, had skin often difficult to remove. Clingstone peaches are the staple for canned peaches but freestone peaches are becoming more popular. The problem with peaches, which look so attractive, is that such attraction is very ephemeral. Fresh peaches have short shelf life without refrigeration, and it was rare to find them being sold on the roadside.

Many years ago, I remember driving the road through the Araluen Valley which runs across the Great Dividing Range from Braidwood to Moruya on the South Coast. The road, especially the last part, was unmade and very rough, and it was here we caught sight of a neglected peach orchard. My companion told me it was the best climate in the World to grow peaches. There was a dilapidated shack on the property which had an overgrown peach orchard. There was a fading sign with a contact phone number and somewhat surprisingly a price – $7,500 for the lot. Even though I did not have that money readily available, and it was a time when I could least afford it, my enthusiasm was unbounded. When she asked me who would help me clear the property, plant new trees, restore the house, I looked at her. She shook her head; the dream evaporated.

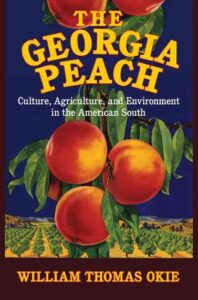

How different from Georgia, where a new book extolling the peach and its place in American folklore, has just been published and an edited review is republished below. How different from here in Australia where the peach is hardly royalty. Georgia is even the Peach State, and Atlanta’s famous street name is widely known due its mention in Gone with the Wind, which introduced the city and its most famous street to popular culture.

During peach season, Georgia’s roads are dotted with farm stands selling fresh peaches. Year-round, tourist traps sell mugs, hats, shirts and even snow globes with peaches on them. At the beginning of the Georgia peach boom, one of Atlanta’s major roads was renamed Peachtree Street. But despite its associations with perfectly pink-orange peaches, “The Peach State” of Georgia is neither the biggest peach producing state (that honour goes to California) nor are peaches its biggest crop.

So why is it that Georgia peaches are so iconic? The answer, like so much of Southern history, has a lot to do with slavery — specifically, its end and a need for the South to rebrand itself. Yet, as historian William Thomas Okie writes in his book The Georgia Peach, the fruit may be sweet but the industry in the South was formed on the same culture of white supremacy as cotton and other slave-tended crops.

Peaches, which are native to Asia, have been growing haphazardly in the United States since they were brought over by Europeans in the 17th century. But it wasn’t until the latter half of the 1800s that aspiring horticulturists began to try and grow the peach as an orchard crop. In 1856, a Belgian father-and-son pair, Louis and Prosper Berckmans, purchased a plot of orchard land in Augusta, Ga., that would come to be known as Fruitland. Their intention was to demonstrate that fruit and ornamental plants could become just as important an industry in the South as cotton, which was ruining the soil with its intensive planting.

Horticulture slowly became accepted as a gentleman’s pursuit. But it wasn’t until the end of the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery that the sudden availability of labour gave peaches the perfect opening. After the war, “fruit growing, which to the cotton planter was a secondary matter, [became] one of great solicitude to the farmer,” Prosper Berckmans wrote in 1876. By the 1880s, Fruitland had grown so large and essential that it mailed 25,000 catalogues every year to horticulturists in the United States and abroad.

Freedmen now needed year-round employment, and the labour requirements of the peach season — tree trimming and harvest — fit perfectly with the time of year when cotton was slow. Though the story of the post-bellum South is often one of industrialization and urbanization, it was also a time of redefining what agriculture would mean without the reliance iof enslaved labour by the plantation owners.

“Cotton had all these associations with poverty and slavery,” says Okie, an assistant professor of history at Kennesaw State University in Georgia.

The peach had none of that baggage.

While King Cotton was still an important part of the Southern economy, town councils began sponsoring peach festivals and spreading marketing materials that sung the praises of Georgia-bred peaches like the famous Elberta Peaches.

“Tellingly,” Okie writes, “the only role mentioned for Black southerners in the great Georgia Peach Carnival was as members of the opening procession’s ‘Watermelon Brigade’ ” — about 100 African-Americans who marched with the racially laden fruit balanced on their heads.

Gentleman farmers saw fruit cultivation as something particularly refined and European, and a craze for all things “oriental” gave peaches an even greater allure. This cultured crop fit in with the narrative white Southerners were eager to tell about themselves after the Civil War. “Growing peaches for market required expertise that seemed unnecessary with corn and cotton, which any dirt farmer could grow,” Okie writes. To succeed, peach farmers had to be able to access horticultural literature and the latest scientific findings. Both required literacy, as well as a certain level of education that was still out of reach for many newly freed men and women.

Before peaches became an important crop, they hung low on branches throughout the South and landowners who saw them as without value were happy to give them freely to slaves. But once peaches were part of the agricultural economy, they became off limits to all but those who could afford them. By the end of the 1800s, Okie writes, a landowner who caught three black children pilfering little more than a handful of peaches charged the father of one $21 for three peaches, threatening the children with a chain gang if he caught them in his orchard again. A labourer working in a city at that time made less than $1.50 per day on average, making it likely that, for a black family in the South, those three peaches amounted to roughly a full month’s wages. What was once freely available to African-American became “a white fruit,” Okie says.

In addition to the cost of the trees and horticultural education, it took three or four years of expenses without income before trees would reliably produce fruit. Peaches required so much capital to grow that few African-Americans could afford to start their own orchard. When women were referred to admiringly as “Georgia peaches,” it was a reflection of their light, rosy skin more than the State. (In an act of reclamation, a black gospel singer born in 1899 as Clara Hudman would go on to use the stage name “Georgia Peach.”)

For better or worse, Okie’s book explains, peaches have become the story of the New South and its environment as much as cotton represents the Old.

The Changing of the MudGuard

“I understand that part of my passion, my job, relates to things I am not a fan of. I am traveling the world, racing cars, burning resources. It is something I cannot look away from, and once you see these things, once you are aware, I don’t think you can really unsee.”

This is part of what Sebastian Vettel is reported to have said in the NYT on the eve of his retirement. Like his contemporary Daniel Ricciardo, he has had a number of lean years since his halcyon days of winning the F1 drivers championship. Ricciardo never reached these heights and instead of graceful retirement, he has opted for the humiliation of demotion to reserve driver.

I believe Formula One motor racing is a blight on modern culture. It is a pollutant, while the so-called “petrol heads” come out to watch very fast vehicles go round and round the same circuit for a couple of hours, polluting the environment with noise and carbon. The concept of being a racing driver retains a certain romantic cachet. Racing drivers are no longer the languid blazerati as epitomised by Stirling Moss and his ilk.

Motor car racing has traded faster and faster vehicles with more and more refinement of the safety features for generally compact, incredibly fit men, with superior reflexes. As one authority has said, a F1 driver needs superior reflexes to respond to sudden changes. An average Formula 1 driver reacts in 100 milliseconds (ms) while the reaction rate of an ordinary person is 300 ms. Drivers always train their reflexes, hand-eye coordination, and peripheral vision. These skills are developed using a special reaction board, where the goal is to hit as many randomly lit lights as possible when they are illuminated.

Thus, men now in their mid-30s begin to lose their sharpness; the current champion driver Max Verstappen is 24 years old. Vettel in his retirement, whether confected or not, recognises that he has been a pollutant, a very wealthy pollutant, but nonetheless a pampered pollutant. He has voiced his concern for the environment, one of the factors he says that has definitely played a role in his decision to retire, seeing the world changing and seeing the future in a very threatened position for everyone, including as yet unborn generations. He is seeking redemption with a variety of projects such as a bee hotel in his native Austria and a public visit to the Amazon at the time of the recent Brazilian Grand Prix as part of his path to atonement.

All very noble, but excuse my scepticism but it sounds as though his retirement is enshrouded in a mist of public relation puffery, rose petals and eidelweiss. Alpine meadows and the uplands far from the madding black exhaust puffery around the streets of Melbourne. Oh, by the way the government expending “environment indulgences” just looks on and forgets to count the cost. And here amid the freebies, nobody there seems to be retiring – voluntarily.

Mouse Whisper

Twitter is showing the true definition of the unexpected consequence, or is it just an extension of Rob Brydon’s long running TV program: “Would I Lie to You?”

A former employee of Twitter twittered:

“I was laid off from Twitter this afternoon. I was in charge of managing badge access to Twitter offices. Elon has just called me and asked if I could come back to help him regain access to HQ as they shut off all badges and accidentally locked themselves out.”